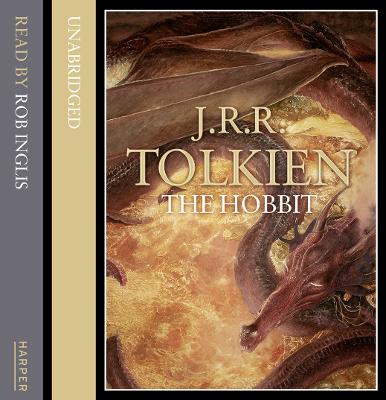

Bilbo Baggins is a hobbit who enjoys a comfortable and quiet life. His contentment is disturbed one day when the wizard, Gandalf, and the dwarves arrive to take him away on an adventure.

The History of the Hobbit presents for the first time, in two volumes, the complete unpublished text of the original manuscript of J.R.R.Tolkien’s The Hobbit, accompanied by John Rateliff's lively and informative account of how the book came to be written and published. As well as recording the numerous changes made to the story both before and after publication, it examines – chapter-by-chapter – why those changes were made and how they reflect Tolkien's ever-growing concept of Middle-earth.

As well as reproducing the original version of one of literature's most famous stories, both on its own merits and as the foundation for The Lord of the Rings, this new book includes many little-known illustrations and previously unpublished maps for The Hobbit by Tolkien himself. Also featured are extensive annotations and commentaries on the date of composition, how Tolkien's professional and early mythological writings influenced the story, the imaginary geography he created, and how Tolkien came to revise the book years after publication to accommodate events in The Lord of the Rings.

This second volume picks up Bilbo Baggins’ story half-way through his journey and chronicles how, after much adversity, he must still face the mighty dragon, Smaug, carry out the burglary for which he has been recruited, and return safely home to Bag-End. But not everything goes to plan…

- ISBN13 9780007316526

- Publish Date 5 January 2009 (first published 1 January 1938)

- Publish Status Permanently Withdrawn

- Out of Print 21 July 2021

- Publish Country GB

- Publisher HarperCollins Publishers

- Imprint HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

- Edition Unabridged edition

- Format Audiobook

- Duration 6 hours

- Language English

- URL http://harpercollins.co.uk

Reviews

Amber

Grace

Briana @ Pages Unbound

The Hobbit follows the traditional quest pattern: a character goes on a predetermined adventure seeking something (in this case treasure) and then comes home again. But the story is often more about the journey than the ultimate goal. The Hobbit, then, is partially about finding treasure, but it is also about the adventures experienced along the way, and some of the story’s most memorable moments come before the dwarves and Bilbo are anywhere near the Lonely Mountain. The book is episodic, but it is supposed to be; it is a bunch of mini adventures that the reader is swept into with Bilbo, and we experience with him a mixture of fear and hope when we wonder what possibly could happen next. We thought the hard part would be getting treasure from a dragon, but it appears there are other dangers in the world. This is a classic literary structure, and it provides the hero with the opportunity to prove himself or prepare himself before he reaches his ultimate goal. Tolkien just turns things a bit upside down by giving his readers an unlikely hero who is physically small, mentally doubtful, and very worried about having left his home without his pocket handkerchief.

Tolkien’s ability to take the classic quest and make it something new, imbued with comedy and joy, is what makes The Hobbit so enjoyable. Reading the book, it is evident exactly how much fun Tolkien had while writing it. He includes funny poems, he describes his characters looking physically ridiculous with their hoods wagging or their big noses sticking out of spider webs, and he makes trolls talk like British cab drivers. He lets us picture Bilbo, his hero, running around in a panic trying to think of a plan. The lightheartedness is somewhat contagious, and it lets the readers know that even though there are cruel goblins and greedy dragons, the world is still good.

Of course, The Hobbit is not completely a comedy. It keeps it roots in literary tradition. Like many good children’s tales, there are a few morals; for instance, it is okay to have a love of beautiful things, but remember that immaterial things are more important. Thorin tells Bilbo, “If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world.” But this statement is more than a warning to children not to be too attached to money; it is a clear echo of the Anglo-Saxon philosophy that characterizes epics like Beowulf. The Anglo-Saxon belief is that gold is a good thing, but it ought to be freely gifted and shared. When a king begins hoarding his gold, he becomes a bad king. (Dragons who keep treasure but do nothing with it, then, are an obvious symbol of evil.) In fact, Tolkien gives a little nod to Beowulf by having Bilbo’s theft of a cup first awaken Smaug.

The Hobbit may not be an epic, but it is a very clever children’s tale. It expertly combines an adherence to and disregard for literary conventions in a way that makes the story seem familiar and complete but also interestingly new. Like Bilbo himself, there is more to The Hobbit than at first meets the eye. Children, adults, and scholars will all be able to find something in this book, even it if is not what they were expecting.

This review was also posted at Pages Unbound Book Reviews.

celinenyx