clq

Written on Aug 20, 2013

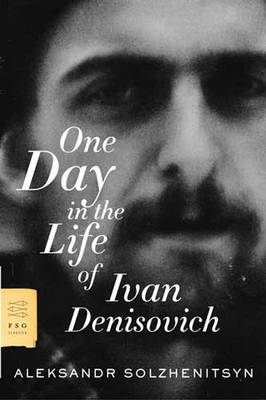

I really, really, liked this book. There is something about the way the story is told that makes it seem extremely realistic, and therefore very uncomfortable. It reads like a viable account of the thoughts going through the head of someone sitting in a Labour camp, and it is made all the more viable by the fact that the author himself spent almost 10 years in a labour camp. It ends on a somewhat surprising note. Not in a moralistic way, but with more of an open philosophical question. One that I have found myself thinking about more than once during the two weeks since I finished the book.

I strongly believe that this is a book everyone should read. It might not be to everyone's taste, but it can be read in a day, and it gives a unique insight into the mind-set and life of someone experiencing what millions of people have gone through. Go on. Read it.