emilybettridge

Written on Apr 6, 2019

Bookhype may earn a small commission from qualifying purchases. Full disclosure.

USA Today's top 100 books to read while stuck at home social distancing

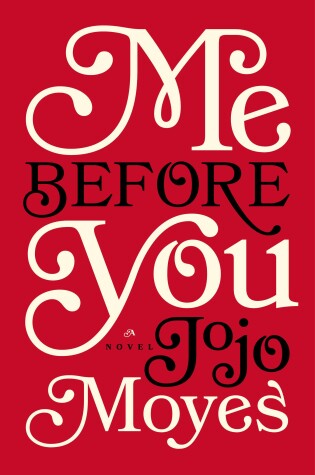

From the New York Times bestselling author of The Giver of Stars, discover the love story that captured over 20 million hearts in Me Before You, After You, and Still Me.

They had nothing in common until love gave them everything to lose . . .

Louisa Clark is an ordinary girl living an exceedingly ordinary life—steady boyfriend, close family—who has never been farther afield than their tiny village. She takes a badly needed job working for ex–Master of the Universe Will Traynor, who is wheelchair bound after an accident. Will has always lived a huge life—big deals, extreme sports, worldwide travel—and now he’s pretty sure he cannot live the way he is.

Will is acerbic, moody, bossy—but Lou refuses to treat him with kid gloves, and soon his happiness means more to her than she expected. When she learns that Will has shocking plans of his own, she sets out to show him that life is still worth living.

A Love Story for this generation, Me Before You brings to life two people who couldn’t have less in common—a heartbreakingly romantic novel that asks, What do you do when making the person you love happy also means breaking your own heart?

(...) live boldly. Push yourself. Don't settle. Wear those stripy legs with pride. (William Traynor)

You only get one life. It's actually your duty to live it as fully as possible. (William Traynor)

He can no longer climb mountains or ski down them or anything close, and he’s susceptible to pneumonia. But Me Before You makes it clear that it’s not the difficulty of Will’s new life that’s the real problem—he admits that he could still have a good life—but that he can’t reconcile what he lost. He was the shiny, bright master of the universe once, and now he’s dependent on others, and because of it thinks he’d be better off dead. It’s a point of view that anyone actually living with a serious disability and, in all likelihood, without the resources to have one’s stables converted into sleek, wheelchair-friendly living quarters, will undoubtably find enraging. But it’s also a galling thing to underlie a romance, despite Claflin doing his best to sell Will as a Byronic hero slowly softening to the warmth of his working-class companion. . . . A drama in which everyone, lips trembling, approves of an able-bodied person’s desire for suicide would be obviously repellent, but in Me Before You, a man’s suicidal ideation is treated as tragic but understandable, his disability making his life less worth saving. Isn’t that romantic? No, it’s really not.

There are so few empathetic depictions onscreen of people whose bodies are different than what we call normal. This film is a squandered chance to illuminate the ways in which bodies function differently but feelings like ardour and lust are universal. Instead, Me Before You is clearly disgusted by the needs of the quadriplegic body and Will’s disability is aestheticized. It is as though the film itself is swaddled in soft cashmere. Through dialogue we hear that Will’s pain and suffering is gruesome, so debilitating that questions of suicide and assisted dying lie not far outside of the shot. And yet, we see none of this “ugly” stuff. Will’s insistence that his is not really a life worth living reads, then, as a cold and insidious insistence that in fact it is the disabled life that is not worth living. By contrast, we can look to Hanya Yanagihara’s 2015 novel A Little Life for a complex and affecting narrative of living with and through pain. Without shirking contentious questions of suicide and trauma, it offers a better love story, too.