“He read a lot. Used a lot of big words. I think maybe part of what got him into trouble was that he did too much thinking. Sometimes he tried too hard to make sense of the world, to figure out why people were bad to each other so often…he always had to know the absolute right answer before he could go on to the next thing.” – Wayne Westerberg, referring to Chris (Alex) McCandless

First of all, this is not just a biography of Chris McCandless. Yes, it tells his story, but then it goes off on several trails of OTHER wilderness-loving solitaries (some of which survived, and some didn’t).

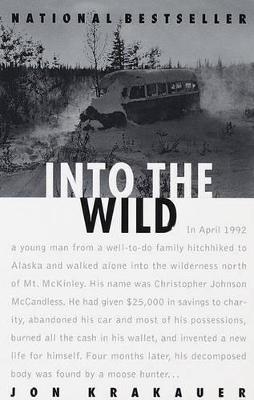

More people have seen the movie than read the book, and from what I can tell the movie is more streamlined. My DH really enjoyed it and has been asking me to watch it with him for at least a couple of years, but I’m very resistant to watching a movie before the book that inspired it. (Don’t even get me started on how I felt about going to see Fantastic Beasts in theatre.) When a friend mentioned he had a copy just lying around, I jumped on the chance. Surprised by how it small it was, I sat down and devoured it…in about 4 hours. Quite a long time for my usual reading speed.

The first couple of chapters are a brief narrative of the events leading up to Chris’ journey “into the wild,” and then the events surrounding the discovery of his body. I was really shocked that part was over so quickly! I was expecting more of a lead-up. But as soon as all the bare facts are out (maybe the result of the Outside article that originally ran on McCandless?), Krakauer goes back in time to dig through McCandless’ early life, then his hobo life after college. I was eerily struck by how similar some of the descriptions of his known thoughts and behaviors were to my own. An introvert, a reader, a thinker – someone who lived inside his own head for long stretches of time – these were all things with which I can easily identify. It was creepy.

McCandless was either a visionary or a reckless idiot. It’s obvious that Krakauer feels he was the former, but I think the judgment could go either way. For someone SO intelligent, McCandless’ intentional self-sabatoge (throwing away the maps, refusing to take advice from seasoned hunters and hikers) is just ABSURD. No matter how pretty his prose, there is no way to explain that part of his adventure away. On the other hand, he made it 113 days, and from the photos and journal he left behind, he was actually doing pretty well until some infected berries made his body turn on itself.

Maybe he was both. The most intelligent people are often noted for their decided lack of common sense. He formed his views on wilderness at least partially from fiction – an extremely dangerous concept.

McCandless read and reread [b:The Call of the Wild|1852|The Call of the Wild|Jack London|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1452291694s/1852.jpg|3252320] and [b:White Fang|43035|White Fang|Jack London|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1475878443s/43035.jpg|2949952]. He was so enthralled by these tales that he seemed to forget they were works of fiction, constructions of the imagination that had more to do with London’s romantic sensibilities than with the actualities of life in the subartic wilderness.

The middle portion of the book delves a lot into other wilderness personalities. I found them interesting, but while in some ways similar to McCandless they are all different enough to warrant their own tales. They feel a bit like filler. Interesting filler, but filler nonetheless.

McCandless’ backstory is filled with drama between himself and his family. He seemed to be more than capable of making friends, yet has a nonexistent relationship with his parents. While purportedly close to one sister…he leaves her without any sort of goodbye. Loner, indeed. Again, I can relate…but cutting off one’s family entirely is almost never a good thing (cases of abuse and intolerance exempted of course). Like Ken Sleight, the biographer of another wilderness disappearing act, Everett Ruess, says:

“Everett was a loner; but he liked people too damn much to stay down there and live in secret the rest of his life. A lot of us are like that…we like companionship, see, but we can’t stand to be around people for very long. So we get ourselves lost, come back for a while, then get the hell out again.”

Again, that quandary is one I feel and have felt very often. Unlike McCandless, I’ve never felt strongly enough about any of it to just chuck my entire life and go off into the woods. Perhaps that’s a lack of backbone on my part. Or perhaps it just shows that I have one.

One of McCandless’ last journal entries:

I have lived through much, and now I think I have found what is needed for happiness. A quiet secluded life in the country, with the possibility of being useful to people to whom it is easy to do good, and who are not accustomed to have it done to them; then work which one hopes may be of some use; then rest, nature, books , music, love for one’s neighbor – such is my idea of happiness. And then, on top of all that, you for a mate, and children, perhaps – what more can the heart of a man desire?

Still a bit on the melodramatic side. What, exactly, had he lived through? A spoiled white child from doting parents that GAVE AWAY his livelihood to wander like an outcast? At the same time…it rings a note of truth there that makes my heart ache. He seems to echo Oscar Wilde:

With freedom, books, flowers, and the moon, who could not be happy?

I’m giving 5/5 stars, based solely on how I felt immediately after finishing the book. Looking at it now I would probably say 4 because of all the extraneous information and meandering.

Blog | Twitter | Bloglovin | Instagram