Reviewed by brokentune on

I realized I could say anything to this person and she wouldn’t be able to hear; I realized that unless she could lip-read she’d not know what I was saying. I could ask her what had happened to her, why and how she was in a wheelchair. I could recite the whole of Kubla Khan by Coleridge, or tell her all about Theseus and Ariadne, and she’d have to listen, while not listening at all, obviously. It had the makings of the perfect relationship.

(from "Last")

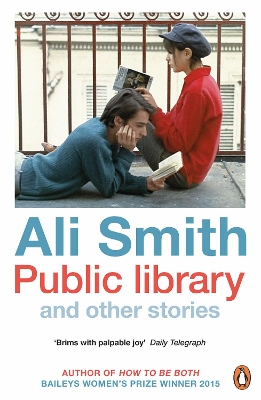

I was looking forward to when this book was first published with all the expectations of a biased fan. It's probably the weakest of the books I have read by Smith (with the exception of an early collection of short stories called Free Love). Some of the stories (The Poet and The Beholder) in this collection were previously published in a different context in Shire, which focused on two writers who have had an influence on Smith in her student days.

And So On was previously published also (in the Guardian I think but might be wrong) and also made more sense as a standalone than as part of this collection.

The collection as a whole, feels a bit rushed. However, I think the feeling of urgency stems from the the underlying requirement to raise public awareness and support for libraries in a time of austerity measures, when libraries were one of the first victims to cuts in public spending. As Smith notes:

Just in the few weeks that I’ve been ordering and re-editing these twelve stories for this book, twenty-eight libraries across the UK have come under threat of closure or passing to volunteers. Fifteen mobile libraries have also come under this same threat. That makes forty-three – in a matter of weeks.

As a witness to other cuts that have affected people's access to information and public spaces in which to socialise, I have to agree with Smith's notion that this is an urgent issue that needs to be raised. Once libraries are closed, it is unlikely they will return.

And isn't it ironic, that only a few months later, the wake of the Brexit referendum would lead to public outcry over an identifiable lack of skills to process information or in some cases mis-information and lack of political education? (It's also fitting that it would lead to Smith's next book Autumn.)

In previous notes about Smith's writing, I have mentioned that she has a particular way of working and playing with words that is both engaging and magical. Or maybe it is magical the way it is engaging? In any case, I love the way she explores words and meaning.

The word last is a very versatile word. Among other more unexpected things – like the piece of metal shaped like a foot which a cobbler uses to make shoes – it can mean both finality and continuance, it can mean the last time, and something a lot more lasting than that.

(from "Last")

One of my favourite aspects of Smith's writing - apart from her magical way of playing with words - is that she is a master at recording personal responses to events, that she can tell about what is going on outside of a person's (or character's) life by describing the inner worlds - sometimes with a smirk:

I’d thought I knew quite a lot about Lawrence’s actual life. I’ve been reading him since I was sixteen, when I chose a dual copy of St Mawr / The Virgin and the Gypsy for a school prize, mostly because I knew it would discomfit the Provost and his wife, who annually gave out the prizes; Lawrence was still reasonably notorious in Inverness in the 1970s. (It makes me laugh even now that the prize sticker inside my paperback says I’m being awarded for Oral French.)

(from "The Human Claim")

....and sometimes with a level of rage:

Meanwhile, in my sleep, the freed-up me’s went wild. They spraypainted the doors and windows of the banks, urinated daintily on the little mirror-cameras on the cash machines. They emptied the machines, threw the money on to the pavements. They stole the fattened horses out of the abattoir fields and galloped them down the high streets of all the small towns. They ignored traffic lights. They waved to surveillance. They broke into all the call centres. They sneaked up and down the liftshafts, slipped into the systems. They randomly wiped people’s debts for fun. They replaced the automaton messages with birdsong. They whispered dissent, comfort, hilarity, love, sparkling fresh unscripted human responses into the ears of the people working for a pittance answering phones for businesses whose CEOs earned thousands of times more than their workforce. They flew inside aircraft fuselages and caused turbulence on every flight taken by everyone who ever ripped anyone else off. They replaced every music track on every fraudster’s phone, iPad or iPod with Sheena Easton singing Modern Girl. They marauded into porn shoots and made the girls and women laugh. They were tough and delicate. They were winged like the seeds of sycamores. There were hundreds of them. Soon there would be thousands. They spread like mushrooms. They spread like spores. There would be no stopping them.

(from "The Human Claim")

Irrespective of the shortcomings of Public Library and Other Stories, and even tho not all of the stories in this collection are memorable, I would recommend the collection on the strength of even one story alone: In And So On, Smith describes the loss of a friend who died too young. In this story she imagines her friend as a work of art who has been stolen by art thieves. This story, friends, epitomises why I love Smith's writing: it's quirky, it's emotionally raw, and it's pure genius.

And in some ways here I am doing exactly that, telling all this in the direction of my friend who died young and was a work of art, no: a work of life, though she died so roughly, and wherever those thieves are hiding her till they can sell her, they have to tape blankets over the windows because the light coming off her mind, even though she’s dead, gives away her whereabouts, and they have to keep pulling up and cutting back the flowers and tendrils and green stuff that persistently crack the stone of the floors of wherever they’ve got her.

(from And So On)

Reading updates

- Started reading

- 17 November, 2015: Finished reading

- 17 November, 2015: Reviewed