Reviewed by Briana @ Pages Unbound on

Note: This is half review/half discussion of the themes presented. It will include references to some plot events, so those who dislike any type of spoilers should not read it.

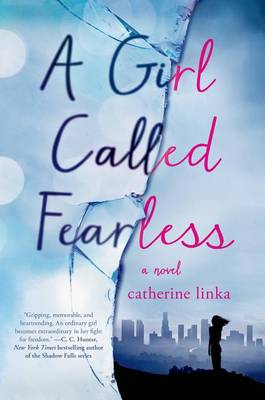

A Girl Called Fearless is a bold novel, exploring women’s rights and sexuality and what it means to be free. It will appeal to many modern young women, who are growing up in a world where the media and politicians debate some of the same issues: what women’s rights are, whether pornography and prostitution are valid ways for women to earn a living, whether women’s sexuality should be promoted or suppressed, whether there is a “war on women” and, if so, who is waging it. However, A Girl Called Fearless is much more successful at raising questions and themes than it is at packaging them within an exciting well-executed plot. I predict a high level of popularity for the book, but it will hinge on readers’ ignoring the fact that it is not well-written and focusing instead on the ideas it presents.

[This paragraph contains spoilers.] The premise promises readers an intriguing and dangerous dystopian world. The summary explains that Avie Reveare lives in a future version of the United States where the political Paternalist Movement is systemically taking away women’s rights: rights to education, suffrage, money, and love. Throughout the book readers and Avie are given hints that something even “bigger” is going on, however, and that Avie might inadvertently become involved. Exciting, right? Suspenseful? Wrong. The “big reveal”, three hundred pages in, is that (drumroll!) the Paternalists are systematically taking away women’s rights. I repeat, the “surprise” is something readers were told since page one. That is both immensely disappointing, and, frankly, baffling.

The entire premise is also illogical. The Paternalist Movement began after the majority of women in the United States died from ovarian cancer from a synthetic hormone that had been injected into beef. The Paternalists, after this tragedy, vowed to protect the women and young girls that were left. Due to the circumstances, one would think “protecting” women would mean requiring extensive research before chemicals were approved for use in food and cosmetics. No, instead, the Paternalists are protecting women by restricting their right to any kind of free movement or thought. That is not a sensible response to an epidemic caused by beef. Granted, there is one line suggesting that men need women to be oppressed so they can get them to start breeding at age fifteen and repopulate the country—but repopulation could have easily been achieved by other methods. Example: Offer incentives for females from other countries to immigrate to the United States. As it stands, the Paternalist Movement is ensuring that no foreign women have any desire to step foot in the country, thus lowering potential birth rates.

So, readers must ask themselves, why are the Paternalists trying to oppress women, if neither their public reason (protecting women) nor their private reason (increasing the population) makes any sense? Are men just evil? Do they just have some innate sadistic desire to control women? There are a few good men in the book, generally the ones under eighteen who get to fill the role of love interests (and one priest!), but the overall depiction of the male population is bleak. This book appears to be promoting strong female heroines at the expense of painting men as the bad guys.

If we accept that the premise of the book does not make any sense, however, and continue reading for individual scenes, things do get more interesting. The cast of female characters is pretty diverse, for instance. Avie and her friends are the “privileged” of the nation, girls who may have no choice in whom they marry, but who get to live “safely” in private gated communities and may have the opportunity to attend college in Canada. Avie eventually learns that she does have some kind of luck in life (money) compared to many other girls. I most enjoyed the depiction of an escort service in Las Vegas. Avie arrives very judgmental of the girls who live and work there, until she learns it’s the only choice some of them have, and that many of them are earning the money to buy their freedom or that of their family members (women can buy out their marriage Contracts, if they somehow manage to acquire the money). It is noteworthy that, in spite of the “defense” of these girls and their lifestyles, Avie herself vehemently refuses to take part in it, even for a day, even for a greater cause. Apparently even a book that wants to look kindly on escort girls knows that its protagonist will not be easily accepted by readers if she becomes one.

A Girl Called Fearless also explores a lot of family dynamics. The interactions between fathers and daughters are a big one. The problem: The men and the older girls all remember the world as it was when women had rights. Naturally, this knowledge causes huge rifts (and we’re back to the question of why most men comfortably go along with the Paternalist movement, when they were raised by and married to lovely independent women, but that’s just not going to be answered). There are also some complex relationships between those who have joined the Resistance and those they left behind. The book asks characters and readers to decide which is more important, family or a cause, or if the two can somehow be balanced.

In the end, A Girl Called Fearless is a book of ideas. It is packaged as a dystopian that excitingly zooms readers across a reimagined nation, from urban areas to rural, but the plot is not what holds the book up. It’s a little too disjointed and illogical for that. However, tons of readers are going to love it for the questions it asks—are men controlling women, why would they want to, is selling your body a form of freedom or of slavery? From my above review, it is probably clear that I am not quite satisfied with the answers that the book hints at for many of its own questions. However, the novel can (and doubtless will) be used as a starting point for discussions about women’s rights, both present and future.

Reading updates

- Started reading

- 15 March, 2014: Finished reading

- 15 March, 2014: Reviewed