Reviewed by brokentune on

There comes at last a moment when the pole is centred in its hole, supported only by the people who surround it, that it becomes clear to some what it means to be Haida – and plain to all how many hands it takes to resurrect a tree.

You looked at the star rating, didn't you? Well, there is a reason why this book only got 2.5* off me, but it is nothing to do with the level of interest with which I read this.

Indeed, I have never thought that I ever would read a book about logging and the North American timber industry - and actually finish it.

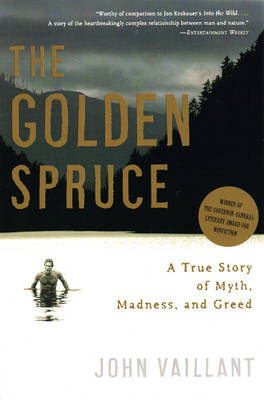

The Golden Spruce started off great with the disappearance of Grant Hadwin, former logger-turned-environmentalist, which is a mystery that has never been resolved. Hadwin's claim to infamy is that he felled a unique tree - the Golden Spruce - an ancient tree that by mutation developed a golden rather than green colour. A tree that became a local attraction and was revered by the Haida.

In telling this story, Vaillant delivers a detailed history of logging in British Columbia, and the history of the relationship between the coastal First Nations and the settlers. The regional history is told in parallel with Hadwin's own life story - starting with his career as a logger and his growing personal issues with the work:

"Grant was struck by the destructiveness of the logging process. Then only seventeen, he described logging techniques that stripped the mountainsides down to bare rock. ‘Nothing’s going to grow there again,’ he told her. This was an unusual thing for a teenager from Vancouver to be concerned about in 1967, especially one with Grant’s lineage. Logging had literally built the city and most people were still connected to the industry – if not directly, then through family members or friends. But things were changing in the sleepy green logging town. Not long after Grant had reported his observations to his aunt on the north side of English Bay, a fledgling organization formed on the south side, just ten kilometres away. They gave themselves a deceptively Canadian name, the Don’t Make a Wave Committee, but this would prove a misnomer, and, in 1970, they would change it – to Greenpeace."

Hadwin's growing concern and developing mental health issues would culminate in his

obsession with the destruction of the natural by the professional classes, and eventually lead to an act of eco-terrorism that had him arrested and charged for the logging the Golden Spruce in 1997. Except, that Hadwin disappeared before he could stand trial.

All in all, I thought this was a fascinating book, not least because the story does not end with Hadwin's disappearance but goes to show that this wanton act of destruction inspired several attempts to recreate the Golden Spruce from shoots which had been taken earlier and the political mine-field that was created by doing so because of the tensions between Haida First Nation attempting to preserve their heritage and the enthusiasts who were trying to recreate the Golden Spruce so it can be grown and exported to willing buyers.

Who'd have known that so much discussion could arise out of the felling of one single tree?

"To get an idea of the scale of logging taking place in the Charlottes during the last thirty years, one need only look as far as the Haida Monarch and the Haida Brave. At the time of their launching in the mid-seventies, they were the world’s largest floating log carriers, and both were built to serve the islands; the Monarch (the larger of the two) is capable of carrying nearly four million board feet of timber (about four hundred truckloads) at a time. When one of these vessels dumps its load at the booming grounds in Vancouver, it can generate a spontaneous wave three metres high."

So, why only 2.5*? I hear you ask: Well, I started reading this book as a paperback but an unfortunate accident involving coffee and a jam doughnut made me switch to the kindle version. I promptly found out that the books were different: the sequence of the chapters did not correspond and even the text within the corresponding chapters did not match. The kindle version read like the paperback had been gone with a chainsaw and then glued back together. Yes the text flowed, but I found myself re-reading parts that I had already worked through.

Which brings me to the second snag - it was hard work reading the book. There is way too much detail about the history of logging - including a short history of the chainsaw and instructions on how to cut down trees. And by "way too" I mean it fine to reveal those details but it distracts from the story if every bit of history introduces new characters which do not add to the story and which are never mentioned again for the rest of the book. No problem if they had been cited in footnoted or endnotes, but trying to force them into the narrative did not work.

I will leave off with a bit of trivia which illustrates the tone of the book - informative, yet, moving:

"PORT CLEMENTS HAS suffered much; not only did the town lose its mascot (the golden spruce is the centrepiece for the town logo), but in November of the same year, its albino raven died in a blinding flash when it was electrocuted on a transformer in front of the Golden Spruce Motel. True albino ravens – as opposed to grey or mottled – are all but unheard of. To get an idea of just how rare these birds are, consider this: Alaska and British Columbia together cover nearly two and a half million square kilometres and contain the continent’s largest populations of ravens, and yet never in the history of bird observation and collection has a true albino ever been reported in Alaska. The Port Clements specimen is the only one ever to have been observed in British Columbia (it has since been stuffed and is now on display in the town’s logging museum)."

Reading updates

- Started reading

- 1 October, 2015: Finished reading

- 1 October, 2015: Reviewed