Reviewed by Michael @ Knowledge Lost on

The Russian title У войны не женское лицо translates to War Does Not Have a Woman’s Face. This should give you a sense of the attitudes women faced. Wanting to serve their country or help in any way possible, these women were often met with opposition from men. Ranging from ‘War is man business’, to a willingness to fight alongside the women but refusing to marry them, and the list goes on and on. The attitudes of these men constantly made me angry, even though these women were constantly proving they are capable and in many cases better at the tasks than the men objecting.

I expected to find a lot more physical sexual harassment in the book but it turns out that men are fragile creatures and once emasculated they just resort to verbal abuse more than anything else. The women in The Unwomanly Face of War have amazing stories and it does make me wonder why more stories like this are not written down. Oh, that’s right, the publishing world was dominated by men for far too long and history is just that, his story.

“I am writing a book about war… I, who never liked to read military books, although in my childhood and youth this was the favourite reading for everyone. Of all my peers. And that is not surprising – we were the children of Victory.”

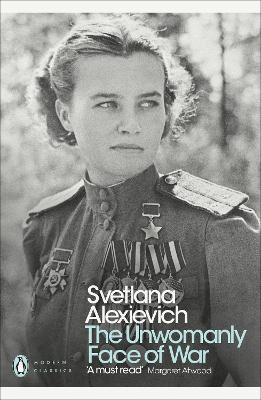

Svetlana Alexievich starts this new translation of her book The Unwomanly Face of War with a reflection on her motivations. I am unsure if this was included in the original 1985 books as there are references on how she would have done things differently. But then again an introduction is probably the last part of a book you would write. I do not have a copy of the 1988 English (translator unknown) so I am unable to compare. The reason I bring up the introduction is because this feels like the first time I have read anything about Alexievich’s thoughts on the book and what she would have done differently if she could do it again. Not vital to the book itself but I appreciated that personal touch.

The 2017 edition of The Unwomanly Face of War has a new translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. While not my favourite Russian translators I could not turn down the opportunity to read another Svetlana Alexievich having previously loved Voices from Chernobyl and Secondhand Time. There is one final book translated into English, Zinky Boys, which is subtitled Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War, which I hope to be able to read soon. Leaving two more yet to be translated into English, The Last Witnesses: A Hundred of Unchildlike Lullabys and Enchanted with Death.

Svetlana Alexievich is only the second non-fiction writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature (the first being Winston Churchhill) “for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time”. After reading her books, it is not hard to see why she was chosen. She has a unique ability to craft and piece together a narrative from a collection of interviews. She is able to get these people to open up and tell their story (whether she coaches them or not is a different story). I find myself drawn to her books not just because I am interested in Soviet history and the experience of the people but simply for the way she stitches her narratives together.

I am so glad I picked up The Unwomanly Face of War, while there was never any doubts about me reading more Alexievich, I was hesitant because of the translation. This is a book that has stuck with me and I am constantly thinking about it. I think about the treatment of women and their stories, but never about who translated this book. If you have never read Svetlana Alexievich before than I would recommend starting with The Unwomanly Face of War.

This review originally appeared on my blog; http://www.knowledgelost.org/book-reviews/genre/non-fiction/the-unwomanly-face-of-war-by-svetlana-alexievich/

Reading updates

- Started reading

- 31 January, 2018: Finished reading

- 31 January, 2018: Reviewed