Trigger Warning: This book features a suicide attempt, and problematic language when discussing suicide.

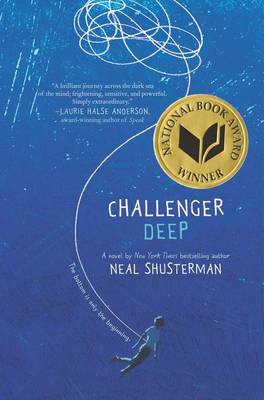

Challenger Deep is an intense and difficult read, but one that is absolutely incredible.

15-year-old Caden Bosch is struggling with his mental health. There's Caden who goes about his everyday life, though now with paranoia, anxiety, delusions, voices, and more, and there's Caden who is on a pirate ship, following orders from the captain. We have chapters both of what's happening in real life, and chapters of what goes through his head, the belief he has about the pirate ship. For the reality side of things, the majority of the story takes place in a psychiatric hospital, and it's once those chapters start that we understand how the captain and the pirate ship came about.

This book is tough, because the chapters on the pirate ship? They make no sense. No sense whatsoever. But at least Caden also knows nothing makes sense, and nothing is how it should be - the crow's nest that looks tiny as you climb to it, but once inside is actually huge and holds a bar; the tiny animals that scuttle around the ship that the swabbie keeps trying to get rid of that you think are rats, but then realise are actually brains; the malevolent captain who talks in riddles - not actual riddles, but he makes sense to only himself. Those chapters were just so confounding, and I was constantly thinking, "What the hell is going on?" It was all so weird and so strange, and I didn't enjoy those chapters at all. And yet... they were really powerful, because you know that these chapters aren't the story, that these chapters aren't real, but an insight into Caden's mind as his mental health spirals out of control. That's one thing that is really clever about these chapters; not only are they what Caden believes is happening, they're also a metaphor Caden's state of mind - the closer they get to Challenger Deep - the deepest part of the ocean, where it's rumoured there is treasure on the sea floor - the worse Caden's mental health is getting. That dive that's planned? Huge metaphor. But god, these chapters were so tough to read. But also really heartbreaking.

Mean while, in the real world, Caden's mental illness/es have several symptoms. Quite a lot really. And it's so, so difficult to see him struggle as he does. He's not just dealing with one thing - like me, I deal with feeling anxious, and the panic attacks that can lead to - but multiple symptoms. Sometimes all at once. Like paranoia:

'I have never ditched school. Leaving school without permission gets you detention or worse. I'm not that kind of kid. But what choice do I have now? The signs are there. Everywhere, all around me. I know it's going to happen. I know it will be bad. I don't know what it's going to be or what direction it's going to come from, but I know it will bring misery and tears and pain. Horrible. Horrible. There are a lot of them now. Kids with evil designs. I pass them in the hall. It started with one, but it spread like a disease. Like a fungus. They send one another secret signals as they pass between classes. They're plotting--and since I know, I'm a target. The first of many. Or maybe it's not the kids. Maybe it's the teachers. There's no way to know for sure.[...]I am free but I'm not. Because I can feel the acid cloud following me. Something bad. Something bad. Not at school--no, what was I thinking? It was never at school. It was at home! That's where it's going to happen. To my mother, or my father, or my sister. A fire will trap them. A sniper will shoot them. A car will lose control and ram into our living room, only it won't be an accident. Or maybe it will. I can't be sure, all I can be sire of is that it's going to happen.' (p102-103)

Delusions:

'There's this thing in my head that I have to purge onto the page before it changes the shape of my brain. Before the colorful lines cut into it like a cheese wire. My drawings have lost all sense of form. They are scribbles and suggestions, random, and yet not. I wonder if others will see the things in them that I see. These images have to mean something, don't they? Why else would they be so intense? Why would that silent voice be so adamant about getting them out?' (p47-48)

What I think is dissociation, but could be completely wrong:

'My friends scarf down their lunches, and laugh about something I didn't hear. It's not like I'm intentionally zoning out, but somehow I can't land myself in the conversation. Their laughter feels so far away it's as if there's cotton in my ears. It's been happening more and more. It's like they're not even talking English--they're speaking that weird fake language the clowns speak in Cirque du Soleil. My friends are all conversing in Cirque-ish. Usually I'll play along. I'll join in the laughter so I can stay camouflaged and appear to be in step with those around me. But today I'm not in the mood to pretend.' (p49)

To hearing voices:

'It's not like I can control these feelings. It's not like I mean to think these thoughts. They're just there, like ugly, unwanted birthday gifts that you can't give back.

There are thoughts in my head, but they don't really feel like mine. They're almost like voices. They tell me things. Today, as I gaze out my bedroom window, the thought-voices tell me the people in a passing car want to hurt me. That the neighbour testing his sprinkler line isn't really looking for a leak. The hissing sprinklers are actually snakes in disguise, and he's training them to eat all the neighbourhood pets--which makes some twisted sense, because I've heard him complaining about barking dogs. The thought-voices are entertaining, too, because I never know what they are going to say. Sometimes they make me laugh and people wonder what I'm laughing at, but I don't want to tell them.' (p104-103)

These are just a selection of examples, but these things happen so often. Caden barely gets a break. And that's when he's cognisant enough to be "in" the real world. But, as I've pointed out, sometimes he is right in there with the captain on the pirate ship. Now, this is one slight negative I have about the book. Once he gets to the psychiatric hospital, and he's about to be admitted, he makes a choice to believe something that isn't true:

'...you being to wonder, Am I on the outside or the inside of that fish tank? Because the rules of "here" and "there" don't have a clear place in your head anymore. You are as much the objects around you as you are yourself. Maybe you are in the tank with them. The fish may be monsters, and you may be afloat on a doomed vessel--a pirate ship, perhaps--unaware of the breadth and the depth of the peril it sails upon. And you hold on to that, because no matter how frightening that is, it's better than the alternative. You know you can make that pirate ship as real as anything else, because there's no difference anymore between thought and reality.' (p132)

And as we get to learn about the hospital, what happens there, the people - staff and patients - that are in the hospital, we can see the parallels between reality and Caden's internal life on the ship. What isn't quite clear to me is if he's able to separate the two? For the most part, it seems like he can; although there are parallels, there is the hospital, and there is the pirate ship, and never the two shall meet. But there comes a point as Caden's mental illness becomes worse, when, for a while, the two become merged. You start off reading a chapter that is on the ship, but then it switches to reality, or you'll have real life chapters, but he'll make comments related to the ship - something to do with the crew, or about the brains, or something relating to a conversation we've witnessed previously on the ship with the captain, but makes absolutely no sense in real life without the context. So for Caden, the two get confused. But does that mean he doesn't confuse them before this point, that he can keep them separate in his head? I don't know. And I suppose it doesn't really matter, and it makes sense that we don't know - Caden is hardly going to pause and speak to the reader and explain what's going on in his head, is he? It's just a niggle that I can easily ignore.

There are other ways that Shusterman uses the fact that this is a story, a narrative, to demonstrate what is happening with Caden. For the most of the book, it's told in first person, both in real life and on the pirate ship. But there are points, as Caden is getting worse, when he talks about feeling outside of himself, that he's not in his head. And as that gets worse, the narration changes to second person. This is so powerful, because it illustrates how Caden is feeling in those moments; he doesn't feel inside himself, so it's "I" or "me" because it's not him, and to show this disconnect, the narration switches to "you" - as you can see in the last quote above.

Speaking of how Caden is feeling, we do get to see him try to put it into words. When talking to his school counsellor, Ms. Sassel, when teachers at his school are becoming concerned about him and his behaviour, although he doesn't say it out loud, he tries to express how he's feeling through imagery and metaphor, and it's just so powerful.

'"Caden, all I know is something is wrong. It could be lots of things, and, yes, drugs is one of those things, but only one. I'd like to hear from you what's going on, if you'd like to tell me."

What's going on? I'm in the back of a roller coaster at the top of the climb, with the front rows already giving themselves over to gravity. I can hear those front riders screaming and know my own scream is only seconds away. I'm at the moment you hear the landing gear of a plane grind loudly into place, in that instant before your rational mind tells you it's just landing gear. I'm leaping off a cliff only to discover I can fly . . . and then realizing there's nowhere to land. Ever. That's what's going on.' (p78)

Challenger Deep also has some quite interesting things to say about mental illness. I really loved this analogy for mental illness, relating it to the "check engine" light on a car.

'It's not like the car manufacturers are much help. I mean, with modern technology, you'd think our cars could diagnose themselves, but no, all there is on the dashboard is this moronic "check engine" light that comes on whenever there's anything wrong--which proves that automobiles are more organic than we think. They're obviously modeled on the human brain.

There are many ways in which the "check brain" light illuminates, but here's the screwed-up part: the driver can't see it. It's like the light is positioned in the backseat cup holder, beneath an empty can of soda that's been there for a month. No one sees it but the passengers--and only if they're really looking for it, or when the light gets so bright and hot that it melts the can, and sets the whole car on fire.' (p107)

Isn't that just so clever and actually pretty spot on? The book also looks at the stigma surrounding mental illness, especially when it comes to loved ones and their views on "getting better", as seen here in Caden's conversation with Callie, a patient who has been to the psychiatric hospital more than once.

'"At home they expect you to be fixed," she says. "They say they understand, but the only people who really understand are the ones who've been to That Place, too. It's like a man telling a woman he knows what it feels like to give birth." She turns to me, forsaking her view for a moment. "You will never know that, so don't pretend that you do."

"I don't. I mean I won't. But I do kind of know how it feels to be you."

"I believe that. But you won't be with me at home. Just my parents and my sisters. They all think medicine should be magic, and they become mad at me when it's not."' (p181)

What I found really interesting about Challenger Deep was how Caden never gets a diagnosis. In a conversation with Carlyle, the man who leads group therapy, we get hints at what he might have (Dr. Poirot is Caden's psychologist).

'Then he asks me if I'm aware of my diagnosis--because the doctors always leave it to parents to tell us. My parents have floated a few mental-illness buzzwords, but only in the vaguest way.

"Nobody tells me anything," I finally admit. "At least not officially to my face."

"Yeah, it's like that at first. Mainly because diagnoses change, but also because the words themselves carry so much baggage. Know what I mean?"

I know exactly what he means. I had overheard Poirot talking to my parents. He was using words like psychosis and schizophrenic. Words that people feel they have to whisper, or not repeat at all. The Mental-Illness-That-Must-Not-Be-Named.

"I've heard my parents say 'bipolar,' but I think that's just because it sounds like a nicer word."' (p212-213)

But then Caden gets to the point where he doesn't feel he needs a diagnosis, because they don't really mean anything:

'There are many things I don't understand, but there's one thing I know: There is no such thing as a "correct" diagnosis. There are only symptoms and catchphrases for various collections of symptoms.

Schizophrenia, schizoaffective, bipolar I, bipolar II, major depression, psychotic depression, obsessive/compulsive, and on and on. The labels mean nothing, because no two cases are ever exactly alike. Everyone presents differently, and responds to meds differently, and no prognosis can truly be predicted.

We are, however, creatures of containment. We want all things in life packed into boxes that we can label. But just because we have the ability to label it, doesn't mean we really know what's in the box.

It's kind of like religion. It gives us comfort to believe we have defined something that is, by its very nature, indefinable. As to whether or not we've gotten it right, well, it's all a matter of faith.' (p299)

As someone who felt better about my mental illness once I knew what it was, what that meant, how it affected me the way it did, this is so interesting to me. Because knowing what's going on with me is part of what helps me get through it. I remember the uncertainty before I was given a definite diagnosis a very scary time. The thought of never knowing for definite what I had, being stuck with that uncertainty, stuck in limbo, is really terrifying to me. So maybe I do want a label for my box, and having some understanding of what inside my box, if I don't know everything. That helps me. But I find Caden's attitude of "I'm never really going to know what I've got, because you can never really be correct, and that's ok," interesting and confounding, but also really kind of inspiring - especially as the story is inspired by Shusterman's son Brendan Shusterman's experience of schizophrenia (so although there's never a specific diagnosis, I think we can assume Caden has schizophrenia? This article in which Shusterman discusses the decisions he made when approaching how to tell this story imply so). That isn't something I could have been ok with, and the fact that he is? That's something else.

I should also point out that artwork is included throughout the story. I knew from t he beginning that the artwork was by Brendan Shusterman, but I thought the artwork was done for the book - Brendan doing illustrations to reflect Caden's state of mind - and sometimes I just didn't understand it. Some seemed to relate to what was happening in the story, but for most, I had no clue what they were supposed to represent. It wasn't until the end the author's note that I realised the artwork included is the artwork Brendan created during his own struggle with his mental illness. Knowing this, reading the second quote in this review makes me realise just how powerful the artwork is, how personal they are, and how wonderful it is that they have been shared with us.

I do have one final thing to say about Challenger Deep, and it's about the language it uses. This isn't a criticism as such, but more me pointing out that this isn't really ok anymore - because not many people are aware. It's to do with how suicide is discussed. There's a moment in the book when a patient attempts suicide, and Caden is never told for definite whether this patient survived or not. It's implied that he has, but in the sense that saying otherwise could be detrimental to Caden's mental health. But he talks about those who "fail" to end their life. That's really negative language, because it implies failure; they didn't get it right. People who don't die after a suicide attempt don't fail, they survive. This kind of language can hurt those survivors. And it also feels like the book is almost judging those who attempt suicide but survive.

'People say a failed attempt is a cry for help. I guess that's true if the person meant to be unsuccessful. But then, I guess most failed attempts aren't entirely sincere, because, let's face it, if you want to off yourself, there are plenty of ways to make sure it works.' (p261)

I know that's not what the book is meant to be saying - the book goes on to talk about if that's how far you're going to be heard, then something is going wrong somewhere in society, and that it's less a cry for help and more a cry to be taken seriously - but it's how it feels, how it reads. It made me very uncomfortable. Imagining someone who survived suicide, or someone who knew someone who died by suicide, read that, and how it would make them feel, troubles me. I think this whole section could have been dealt with better. (For more info on language you should and shouldn't use when discussing suicide, read Beyond Blue's article Language When Talking About Suicide, and Emily X. R. Pan's thread on the topic.)

But overall, Challenger Deep is a deeply affecting, really powerful look at mental illness, one that makes you sit up and think. It's by no means an easy read, but it's one I think we all should.