brokentune

In the dead of night, more snow began to fall, like billions of white, silent tears.

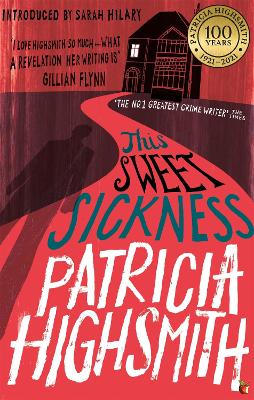

This Sweet Sickness was my 13th book by Patricia Highsmith and you would have thought that by now I would know what to expect and would be able to foresee certain themes or twists. The thing is, I can’t.

One of the very aspects that keeps me reading her books is that I have yet to find a story that follows a formula, or even one that I have encountered in other books of the same era. Sure, some later books may have borrowed from or may have been heavily inspired by her work, but I truly cannot say that I have ever met a Highsmith story that was not expertly crafted and unpredictable.

Unpredictability is not the only element that kept me reading this particular book in every free minute I could find. After a relatively slow start in which we are introduced to David Kelsey, a man in his late 20s, who rents a room in shared house, appears to work in science, and who is in love with a girl named Annabelle.

Little by little, we learn that what we know of David, might not be true. We learn that he leads a double life, that his friends are not all that they are cracked up to be, and that Annabelle… Well, the less said about Annabelle, the better.

The problem is that David’s obsessions have taken over his life and we spend a great deal of page time watching David living a life on the edge, where anything might tip him over at any moment.

It must be great, David thought, really great to have such a high, unchallengeable opinion of oneself, to think that everything one did or possessed or thought or maybe even felt was the best and the finest in the world!

And because this is a Highsmith novel, and if we know anything by now it is that the author loved to torment her characters to see what they are made of, the house of cards that David has so carefully constructed comes crashing down one winter’s day.

I truly disliked all of the main characters in this novel. David is obnoxious. His obsession with Annabelle is crazy for way too many reasons to list. Yet, I cannot dislike him as much as the people who form his closest circle.

His so-called friends are pathetic. They are enablers who feed of David’s mental instability. Worst of all, however, is Annabelle. Annabelle is a devious user who is too flattered by David’s attentions to send him away or try anything meaningful to help him. She toys with him but then is offended that he would like to be part of her life.

The reason I cannot dislike David more than the other characters is that he obviously struggles with reality and reason. As much as I raged at the book whenever David came up with another stupid idea, there was no reasoning with David. He simply did not have the state of mind required to use that faculty. And while there were some parts that reminded me of everyone’s favourite Highsmith sociopath Tom Ripley, there was something much more human to David than there ever was in Ripley – David actually did have a capacity for friendship and caring for another person – and I don’t mean Annabelle necessarily; he also showed kindness to Mrs Beecham.

Women! Their prattling little minds and tongues, their so-far-and-no-furtherness, but please come so-far, and their tedious obsession with the idea that human bliss is based on getting a man and woman in the same house together!

He might have wanted to come across as superior and arrogant, he might even have succeeded at times, but really when it comes down to it, David wanted to just have what he thought was a normal life.

It was very hard to watch David unravel as he did.

He ran into a tree, hurting his shoulder and the right side of his head. It was vaguely familiar to him, the action of running into a tree. Where? When? He went slowly back to the tree and put his hand on its rough, immovable trunk, confident that the tree would tell him an important piece of wisdom, or a secret. He felt it, but he could not find words for it: it had something to do with identity. The tree knew who he was really, and he had been destined to bump into it. The tree had a further message. It told him to be calm and quiet and to stay with Annabelle.

‘But you don’t know how difficult it is to be quiet,’ David said. ‘It’s very easy for you—’

Despite all of the sadness and insanity in This Sweet Sickness, I liked it just a little bit more than some other of Highsmith’s novels. There is a depth to it that sets it apart from other books. The first book in the Ripley series was a thriller that had been magnificently executed. The Cry of the Owl was a page-turner but essentially also a thriller. The Tremor of Forgery was an experiment in existentialism that was also very interesting. But none of them gave me as much cause to think about the main characters in their time as this one and The Price of Salt (aka Carol).

This Sweet Sickness made me uncomfortable, but that was nothing compared to the feeling of sadness I had when thinking about what alternatives there could have been for David. What help would have been available to him in 1960? What treatments may he have had to suffer?

This was a great book, but as with most of Highsmiths’ work it is not a light and fluffy diversion.

He had been here so often before, he thought, in the center of a meager circle of possibilities, each of which offered essentially nothing.