pamela

Written on May 19, 2014

I think I will annoy a great many people when I say that not only did I not love these books, but I didn’t even particularly like them. The stories were undoubtedly gripping, but overall I found them shallow. They profess to tackle significant issues regarding sexual violence, especially violence against women. Still, I feel they addressed them in a way that was just as exploitative as the actions Stieg Larsson so professes to hate. The books are pure voyeurism, and the characters were fundamentally unlikeable and completely two dimensional. We never got to know them as people, simply as the concepts they were meant to represent.

The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo introduces us to characters who will play a role throughout the series. It tells the story of Journalist, Mikhael Blomkvist, and computer hacker Lisbeth Salander. Blomkvist has recently been tried and charged with libel, and with his career on the rocks takes the opportunity to work on the case of the murdered of the niece of business mogul, Henrik Vanger. In return, he will be offered the chance to clear his name. The case brings him in to contact with Lisbeth Salander. They work together (and inexplicably sleep together) to not only solve the case but to uncover a great many other family secrets, only to ultimately (in my opinion) destroy their integrity.

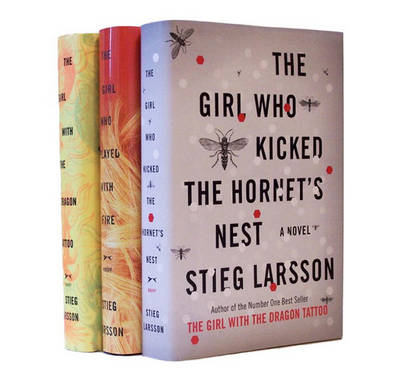

The next two books, The Girl Who Played With Fire, and The Girl Who Kicked The Hornet’s Nest, follow the same story arc. It is essentially a story revolving around clearing Lisbeth Salander of murder charges while they research the case of sex trafficking, and political intrigue in Sweden. Naturally, there is more to the stories than this, but I can’t go into too much detail without ruining the suspense of the books.

The suspense, unfortunately, is all the books have going for them. The real tragedies that occur in the novels, the violence, rape, sex trafficking, etc., are lost entirely in pages of pointless rambling about the sexuality and sexual exploits of the series’ protagonists. The victims of these horrible, dehumanizing crimes, are lost and hardly mentioned, then replaced instead with descriptions of shallow characters, with shallow lives, who have shallow sex, and write shallow articles. The fate of a young Eastern European girl who has been kidnapped and forced into the sex trade is deemed far less critical to the plot than the relationship between a man writing an article on sex trafficking, and his thesis writing girlfriend. They are, after all, ‘the good guys’. Again, the stories of countless women murdered, and tortured in the first book are deemed far less important to the plot than the fact that one woman doesn’t want her secrets told. There is no way this can be redeemed in my eyes. The victims are given no character, and instead, we have to sit through pages of incidental detail about the tiniest moments in the lives of these superficial protagonists and their sex lives.

Larsson’s disgust of sexual violence purportedly inspired the series after he witnessed the gang rape of a young girl when he was 15. He allegedly never forgave himself for failing to help the girl, who’s name was Lisbeth. While this sentiment is admirable, in my opinion the books fail in their objective of absolution. Perhaps these books were meant to be an homage to a woman who was a victim of a terrible crime, but the injustice is furthered by sensationalizing something that affects the lives of so many. Misogyny, sexism, sexual violence - they are all real things. The book doesn’t glorify them, but it gives the reader exactly what the author thinks they want; more of it. Instead of writing sympathetically he – taken from his own website – “knew what ingredients a good detective story should have, and [Larsson] even reluctantly decided to spice it up with a bit of sex as it would probably please his readers.” A bit of sex? These books are some of the most graphically, sexually violent books you will ever read, and that constitutes a bit of sex? Put in there only to “please the readers”? For me, this is raping your characters all over again. If the sex was put in there only to please readers, and what readers want is sexual violence, then the writing thereof is nothing short of exploitative.

The character of Lisbeth herself is interesting, in that she metes out her own form of vigilante justice. She is meant to be a role model, but she is just as typecast and stereotyped as anyone else in the books. The way she dresses, her penchant for fetish style clothes, her genius-level mind, all serve to give an image of a woman who is out of the ordinary; a social outsider. The men in her life judge her, become sexually attracted to her, and in some cases sexually abuse her. There is not a single man in the books who is a friend who is not inexplicably sexually attracted to her, for no other reason than that she is ‘different’. Of course, a sexual relationship has to begin between Blomkvist and Salander, which serves no narrative purpose, and peters out after the end of the first novel as he embarks on several other sexual exploits which in turn serve no narrative purpose. The only man who is her friend and who does not seem to want her sexually is Poison, a fellow computer hacker. But he is described as a fat, socially inept computer geek, with some form of implied agoraphobia who lacks personal hygiene and basic human cleanliness. Therefore, he too fills a stereotype.

Salander is often described as violent, but with her own internal moral compass with its version of North, as if that is meant to make us excuse her behaviour and actions. She is a social outcast because she has made herself one. Her moral compass points to Nietzsche’s Superman Theory all over again. While Salander has been through a lot, she is not above the law, she cannot do whatever she wishes, and she cannot treat people however she wants. While she understandably has issues with authority, these issues are exacerbated by her actions to the point of psychopathic. She is described as sociopathic and socially incompetent, and I am inclined to agree with those sentiments. She is encouraged at every turn, and her illegal activities are hushed up because they prove useful to the journalist protagonists. She is not likeable, she is not a role model, and I don’t think she serves as a good illustration of the power that women can hold, especially in combating sexual violence. Most judicial systems do fail to punish the perpetrators of heinous crimes adequately, but ultimately the real victory goes beyond just punishment. Victims often lack support, so a colossal personal win is how they carve a place for themselves in a world that betrayed them. Some things can never be forgotten, forgiven and excused, but the triumph lies in not letting it ruin, and control your life. In Salander’s case, this is precisely what has happened. Her entire personality and all her actions are driven by her inability to combat her demons and come through her experiences personally victorious.

The plots of the three novels are odd. Each follows the formula of a simple case turning in to something bigger. These novels are different in the cases they pursue, but they become overshadowed by the personal lives of the protagonists. Research into sex trafficking is dominated by the double murder of a journalist and his academic girlfriend, as well as the pickle Lisbeth Salander finds herself in regarding her supposed role in the killings. While eventually, the stories tie in to be part of the one big whole, this is just another case where things turn out just a little too conveniently. Everything is one big coincidence after another, and ultimately the fate of an unnamed Eastern European victim of sex trafficking is deemed less important than Salander’s ultimate revenge and pardon, or Millennium Magazines annual sales.

I could continue and complain about the rambling, detailed, completely unnecessary descriptions of almost every detail, mainly of her ‘gear’. I am not kidding when we find out that she owns an Apple iBook 600 with a 25GB hard drive, and 420MB of RAM (outdated as most of the technology is from 2002), an Apple iMac G3, and the long, incredibly detailed description of her Apple PowerBook G4, which we’re told has an aluminium casing, and “PowerPC 7451 processor with an AltiVec Velocity Engine, 960 MB RAM and a 60 GB hard drive” (The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, page 216). I’m a techie, but even I think that these descriptions are unnecessary. They don’t serve the plot in any way; the specs were already outdated by the time the books were released and so failed to impress on any permanent level. If you’re interested in some more detailed descriptions of gadgets, or even just a trip down electronics memory lane, check out this website: The Girl With The Insanely Long Gear List. This doesn’t even begin to mention the significant number of times that IKEA is mentioned. Apparently, no other furniture stores exist in Sweden, because we are subjected to a long product list of IKEA furniture with which the characters furnish their homes and offices. They even using IKEA to give directions, i.e. turn left when you get to the IKEA. Also, I have the feeling that a company called Billy’s was possibly paying Larsson to plug their ‘Pan Pizza’s’ as every time Lisbeth Salander makes herself a meal, instead of just stating that she ate a frozen pizza, it is mentioned every time that is was ‘Billy’s Pan Pizza’. Unnecessary. One day I will go through these books and count ever time those words are mentioned, every time coffee is mentioned, and every time someone talks

about someone that they’ve slept with, especially Blomkvist. I have a feeling I’d reach the word count of one whole novel.

All in all, the books are gripping, the plot drives you forward, you’re interested in what happens, but I still can’t like them. They fly in the face of everything they’re trying to achieve, using sexual violence to increase sales, rather than to raise awareness. These books have been described as feminist, finally giving women several strong, female, literary role models, but I disagree. All I see is a man who chose to exploit women in his own way to gain literary fame, in the guise of writing strong female characters. Characters who, like so many others, eventually do come to rely on the men in their lives. Perhaps that’s the real tragedy; the idea of the ‘us and them’ mentality. It doesn’t need to be. Women don’t need to be fine without men, the same way that men don’t need to be fine without women. We can need each other, not as gendered beings, but as people. Our survival and sanity depend on it.