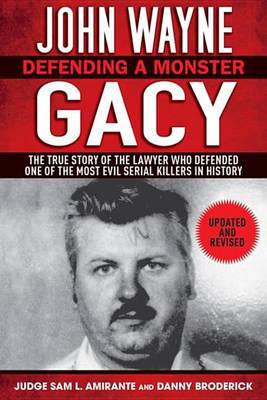

So, this book is written by Gacy's lawyer. He opens the book talking about the Constitution and the Sixth Amendment.

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

He is a firm believer that everyone, even someone as horrible as John Wayne Gacy, deserve the right to an attorney. Now, he knew Gacy in passing prior to taking his case and didn't know exactly what was going on at the very beginning. Once he learned more, he stuck to his guns that even Gacy deserved counsel. Even when people issues death threats to him and his family, including his children (I do not understand how anyone can think issuing death threats to children would ever put you on the right side of history).

He tells the story of Gacy's past by starting with how the final kill that got the cops following him. This boy was Rob Piest, fourteen years old. He was working part-time at a drug store when he learns that Gacy pays really well to help with construction work. Rob wanted to get more money to buy a Jeep that he's had his eye own. So he approaches Gacy about a job, saying he would do anything for money. Gacy took that as not just construction work but also sexual favors. When Rob turns him down on the sexual part, Gacy looses it. Prior to Rob Piest, Gacy took boys from the fringes that didn't have people with the resources to look for them. He was taking prostitutes and the like.

The author goes into all the talks that he had with Gacy throughout the investigation and then the trial. It doesn't take long to figure out that Gacy isn't sane. At one point he comes to the office of his attorney and his co-counsel and goes into a drunken, rambling confession of everything that he had done. He would go into a tirade about how he wasn't gay (using a lot of gay slurs that I will not include here) and then quickly go into the first time he had sex with a man. A friend convinced him that a blowjob was the same no matter who was giving it. But he did have sex with men too.

I know these are really long snippets, but I think it really gives insight into Gacy.

After returning from Joliet and the bridge over the Des Plaines River, with Gacy incessantly begging to go to the cemetery, the next stop was Gacy's house. Gacy had admitted that there was at least one body buried on his property that was not in the crawl space, and the prosecution wanted to know exactly where it was. Further, when an accused person points out where the bodies are buried, whether figuratively or actually, it strengthens the State's case. In the event that the defendant later recants and denies his involvement in a crime, the prosecution has evidence that the defendant knew or was aware of information that only the perpetrator could possibly know.

I had advised against all of this, of course, but Gacy was on his "frolic." No one could convince him that he should stop doing the job that the police are paid to do. Frankly, as crazy as this sounds to you and me, Gacy loved the limelight; he loved the attention. It didn't seem to matter that the reason that he had the limelight trained on him was that the prosecution was building a case for murder. He was in his element. How weird was that?

Gacy's entire block had been cordoned off from all except public officials, cops, and those that were unlucky enough to have a house on it. There was a lull in the activity because jurisdictional concerns were being sorted out and new warrants were being obtained to allow a complete and extensive search of the house and excavation of the crawl space. We pulled up, and a brand-new flurry of activity was generated throughout the members of the press and others that were hanging around on the fringes of the crime scene.

Gacy was brought into his garage.

If you've ever wondered what your first concern would be when you are brought back home after being charged with the murder of a missing boy and you are the prime suspect in the murder of many, many others, well … apparently, if your name is John Wayne Gacy, your first concern would be the fact that the police that had been conducting a search of your home had left some things—some tools and some other items—out of place in your meticulously kept garage. Gacy immediately started bitching about this mundane issue as if he was going to be back in an hour or so and he was going to have to clean up the mess all by himself. He began picking up items and placing them gingerly into their predesignated spots on walls and in drawers. If not for the solemn gravity of the situation, which was completely lost on this strange little man, it would have been hilariously funny. What was wrong with this guy?

Finally, someone reminded my client that he was not there to clean the garage.

There were moments during this time, this experience, that stand out in my memory. It is all an incredible experience, of course, a tornado of activity. My first case as a private criminal defense attorney was becoming quite an interesting ride. But some moments stand out. What Gacy did next caused one of those moments.

He took a can of black spray paint and drew a box on the concrete floor of his garage. Then he drew an X in the middle of the box.

"Dig here," he said. It was like he was pointing out the spot where a buried water meter could be found. If the foreman of a crew charged with the responsibility of digging a trench for a water main was totally bored with his job, he couldn't have said it more nonchalantly, more offhandedly.

"Do you know who is buried here?" one of the guys asked.

"Yeah … Butkovitch."

John Butkovitch had eaten dinner at John Gacy's house. This kid was a particular friend to Gacy's ex-wife Carol. Little John, she called him. There was Big John and Little John. What a kooky pair, always together. John knew this kid's father. John had helped decorate Little John's new apartment. Little John was a regular visitor, a valued employee, a friend.

Now he was under concrete in Gacy's garage.

What was wrong with this guy?

As it turns out, Jack Hanley was a real person—sort of. Plus, he was really a cop. It seems that Gacy and Officer Hanley had met sometime while John was working at Bruno's, a restaurant where he worked for a while as a short-order cook after he was released from the prison in Anamosa. Of course, Officer Hanley's name wasn't actually Jack, but in John Gacy's wandering, lost mind, it was. Officer Hanley was not a homicide detective either. However, if you asked John, he would tell you that he was.

Without explanation, John Gacy would occasionally use this name when cruising Bughouse Square. He always believed that it was much cooler to say he, John Gacy, was a homicide cop named Detective Jack Hanley, a suave badass who solved the unsolvable crimes, rather than the truth—that he was a dumpy, boring smalltime contractor who lived with his mother in the suburbs. Now in his defense, John Gacy was not the first guy in the world who has told a little white lie in an attempt to get laid. I have seen a lot of multimillionaires with really bad shoes and worse haircuts in meat markets and watering holes. Most of these stories fade with the morning sunlight as the alcohol is metabolized and eliminated from the body.

For some unexplainable reason, though, John Gacy decided that it would be in his best interest to claim that Jack Hanley was his alter ego, his second personality. Unlike other men who have lied in pursuit of poontang, John seemed to adopt Jack as a second persona. So when John was flitting from cop to cop and prosecutor to prosecutor confessing his awful crimes like a bumblebee goes from flower to flower, he was telling many of them that John Gacy did not commit these grotesque acts—Jack Hanley did.

Now please keep in mind that Gacy did not mention the name Jack Hanley during the endless drunken ramblings that spewed forth during his soul-searching confession at my office with Leroy Stevens. However, he suddenly had a second personality buried deep inside when he told his story to the police. This was simply Gacy being Gacy. John always knew best, you know, or so he thought. These were self-serving statements—a silly, uninformed attempt to set into motion some sort of flimsy departure from reality.

What this accomplished, together with the fact that Mr. Gacy could not simply just keep his mouth shut, was to set in stone the only defense available to him. Motta and I would have no choice in the matter. We would be required to assert the insanity defense at trial. It was John himself that left us no other alternative. Oh yeah, there was one other reason why we were limited to asserting the insanity defense: John Wayne Gacy was certifiably, without a doubt, with all certainty batshit, bonkers, cuckoo, crazy, insane. This fact would become painfully obvious over time.

Narration

The narration of this book was really good. I know from talking to Lorelei King about her narration of Ted Bundy's book how hard it is to read about the horrible stuff these people have done in their life. I'm sure Robin Bloodworth would feel the same way. He did a great job.