Review also posted at Pages Unbound Book Reviews.

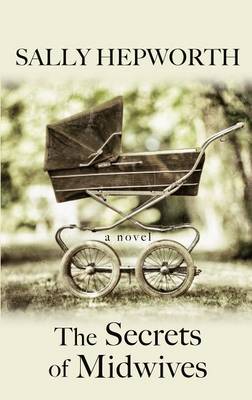

To start, let me say that I understand why this book is being published. Although the ARC cover features a pile of green baby blankets, the final cover has a photo clearly meant to call to mind Call the Midwife and capitalize on the popularity of the television series (a fact that becomes even clearer when one realizes that The Secrets of Midwifes takes place in present-day Rhode Island, with only a few flashback to a time when midwifes were riding bicycles and wearing blue dresses with red cardigans). This book, delineating the history, secrets, and relationships of three generations of women, also has clear book club appeal. I can see that it is going to sell. It is less clear to me how much readers will enjoy the book after they buy it.

The first major issue with The Secrets of Midwives is bad prose. This is, of course, something of a subjective issue. However, I have shown my ARC to enough people and skimmed enough Goodreads reviews to note that I am not in the minority when I say the writing is something the reader will probably have to ignore or overcome in order to enjoy the book. I showed the novel to a friend who refused to stop reading after the first paragraph. I probably would have done the same if I were in a bookstore, skimming the book and deciding whether I wished to purchase and read it. Primarily, I finished reading The Secrets of Midwifes because I received a review copy and felt obligated to do so. To allow other readers to make their own decisions, however, I will quote the first paragraph (AS IT APPEARS IN THE ARC; the finished book may read differently):

I suppose you could say I was born to be a midwife. Three generations of women in my family had devoted their lies to bringing babies into the world; the work was in my blood. But my path wasn’t so obvious as that. I wasn’t my mother—a basket-wearing hippie who rejoiced in the magic of new, precious life. I wasn’t my grandmother—wise, no nonsense, with a strong belief in the power of natural birth, I didn’t even particularly like babies. No, for me, the decision to become a midwife had nothing to do with babies. And everything to do with mothers.

This certainly isn’t the passage of the novel I experienced the most annoyance reading. But it is the place where many readers will have to decide whether they wish to keep going.

In addition to mediocre prose, the book employs a difficult structure, switching each chapter to give the point of view of Neva (the daughter), Grace (the mother), or Floss (the grandmother). This in itself is unproblematic. However, Hepworth does not employ her multiple points of views in (what I would consider) the most profitable way. Readers get the very basics from Hepworth’s technique: they get a window specifically into each woman’s mind. However, there is no obvious reason any woman is narrating any particular chapter. Hepworth literally opens the book with the three meeting for dinner, and switches the point of view in the middle of this dinner. First readers get Neva’s perspective on drinking tea; then they get her mother’s. I don’t think anything is really gained by the switch, and I wish Hepworth would have more thought into who should tell what part of the story, instead of employing a very basic 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 pattern as the characters switch off.

The multiple points of view do highlight one thing, however: the skill and subtlety with which Hepworth draws Grace. Readers are initially introduced to Grace through Neva, who, although fairly close with her mother in one sense (they hang out a lot, talk a lot, etc.) is not actually on good terms with her because she finds her overbeating and obtrusive. Hepworth then gives Grace’s perspective, and somehow manages to convey the sense that, yes, she is a somewhat meddlesome woman who doesn’t know how to leave people alone, while eliciting some sympathy for her because, in her own mind, she always has a rationalization for her actions.

The other characters do not come across quite as nuanced to me. The possible exception is a love interest, and there readers get the pleasure of seeing his actions and complicated decisions simply as actions—he does not get to narrate his own tale.

With prose, structure, and most of the characters disappointing me, I was left reading with the hope that the plot would be interesting. In some ways, it is. The book claims to be about secrets, after all, and there is one primary mover: Who is the father of Neva’s baby? So, while ultimately I was actually bored by most of the plot, I was hooked by the cheap suspense tactic. I wanted to know who the father was. Unfortunately, this tactic can only work on readers once. I know who the father is now and nothing else particularly captivated me about the book; I have no reason ever to reread it.

Neva’s grandmother Floss also has a secret, but I did not find it quite as compelling. In actuality, hers may have been more surprising. The book definitely leads readers to one obvious conclusion, only to hint later that maybe that is not the right answer, after all. However, I was not personally invested in the technicalities of Floss’s past life, and while I think she does have a good reason for having kept that secret, I don’t think it comes across as that persuasive in the narrative. A one-line explanation for why someone has hidden something for her entire life, and then a moving past that moment, is not too provocative.

The Secrets of Midwives is simply not the book for me. With poor prose and a generally flat plot, it did not give me much to read for. The scenes of the actual midwifery will probably be appealing to many readers. However, I think Call the Midwife manages to get themes of the beauty and difficulties of life and motherhood across more compellingly, so anyone who has seen the show—and buys this book because they have seen the show and are now interested in midwives—might be disappointed by the book’s comparative lifelessness. I’m disappointed I could not like the book more, but I predict the book will have a lot of commercial success, my opinion notwithstanding.