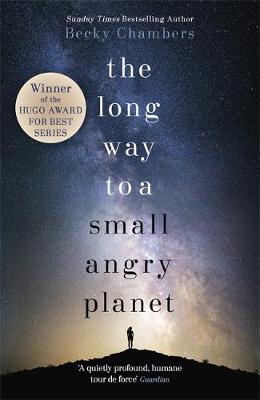

Not only is The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet great sci-fi, but it goes against the sweeping scope of the genre and feels far more compact and homely. It's a character study as much as anything else, and it's written in a way that feels like a realistic depiction of our future in which humans carry with them the same flaws as we have in our current global society. It tackles the small issues with as much detail as the more universal ones ranging from family and personal bias, all the way through to colonialism and xenophobia. It takes from fantastic, story-driven sci-fi of other mediums like the Mass Effect game series and the TV show Firefly, but doesn't feel derivative.

To some Humans, the promise of a patch of land was worth any effort. It was an oddly predictable sort of behavior. Humans had a long, storied history of forcing their way into places where they didn't belong.

Each character was given equal weight in the story. We can probably say that Rosemary, the new clerk on the Wayfarer, is the protagonist, but it is soon obvious that the other characters are equally important, and the narrative jumps between crewmates giving each and every one of them their time to shine. It's about the crew of the Wayfarer as a whole rather than about any of them as individuals. Ashby, the captain is constantly trying to juggle the differences in his crew who come from different planets and cultures. The human crew can't always understand Sissix' (the first mate) species freedom of physical and emotional expression, Their navigator, Ohan, is from a species that experience the world in a unique way, Dr. Chef (the ship's doctor, and chef!) is from a species that is all but extinct, and Lovey is the ship's AI. Each have unique personal and cultural traits that are explored. Even the human crew of Rosemary, Ashby, Kizzy and Jenks (the ship's engineers) and Corbin, the xenophobic Algaeist are completely unique with their own drives and motivations. The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet is as much about the differences between individuals as it is about the bigger differences of culture, race and religion that shape who we are.

For my part, I think that the best explanation is the simplest one. The galaxy is a place of laws. Gravity follows laws. The lifecycles of stars and planetary systems follow laws. Subatomic particles follow laws. We know the exact conditions that will cause the formation of a red dwarf, or a comet, or a black hole. Why, then, can we not acknowledge that the universe follows similarly rigid laws of biology?...I believe this is why many of my peers still cling to the theories of genetic material scattered by asteroids and supernovae. In many ways, the idea of a shared stock of genes drifting through the galaxy is far easier to accept than the daunting notion that none of us may ever have the intellectual capacity to understand how life truly works.

For a book that is essentially about a journey, the pacing is perfect. The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet not particularly action driven. It's moved along by the everyday things that would motivate a commercial vessel. In the background of the plot are universal politics, alliances being formed, wars being fought, and laws being broken. And yet, none of this impacts the crew of the Wayfarer in any way that wasn't entirely believable. There are no high-speed chases, cunning jailbreaks, dramatic exits or space battles. Instead, we follow the Wayfarer with a job to do. Even the personal differences in the crew served to move the plot. There were no breakups or makeups, just so-what?'s and let's-just-try-to-get-along-as-best-we-can's and that's what made The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet so perfect. It was real.