Reviewed by brokentune on

Inspired and motivated by Lillelara's review, I found Into the Wild on my library's OverDrive as an audiobook - I had heard that the book The Golden Spruce, which I recently read, was often compared to Into the Wild and really wanted to find out what led to the comparison.

Having read the book, I can't say I see many similarities at all. The Golden Spruce is about an ex-logger turned environmental activist in British Columbia who commits an act of eco terrorism.

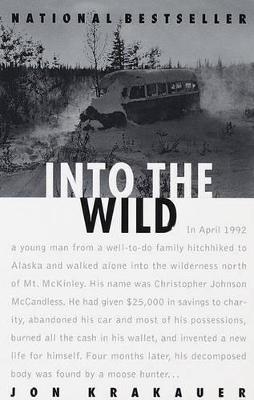

Into the Wild is the story of Chris J. McCandless who who at 24 decides to step out of society and live alone in the wilderness of Alaska.

Both men suffer the consequences of their decisions but this is where the similarities end. Certainly, there were no similarities in their background or motivations.

Before I go off on a rant about Into the Wild, I would like to make clear that my issues with the book are with the writing and the author. The story of Chris McCandless is certainly worth telling and worth thinking about - after all it is quite extraordinary that anyone would choose to go out into the wild and be completely cut off from all human contact. While I'm not sympathetic to McCandless or feel any particular like or dislike towards him for abandoning his family and friends, I respect his attempt (for whatever reason) to live in a way that seemed right to him. Whether he did it out of youthful hubris, out of a peculiar mental disposition, or because he was suffering from some romantic illusion instilled by his love of Thoreau and Tolstoy. At the end of the day, he knew the risks of living in the wild.

My rating of this book is not a reflection of my respect for McCandless' story. The issues I have with the book are with the overindulgent writing and an author who tries to give meaning to McCandless' actions but will over and over try to push his own interpretation of events.

Sure, Krakauer makes a great effort in interviewing a lot of people who may have known McCandless, but instead of presenting the opinions of the people who knew that young man first hand, Krakauer interprets the interviews himself. It may be that he tries to fill pages or it may be that he felt he could add some needed context, but the first time his style of revealing the story really grated on me was when he presented an interview with McCandless' father and then proceeded to dismiss McCandless Snr.'s notions in favour of Krakauer's own ideas of why Chris had chosen to seek seclusion.

Given the choice between a parent's take on the story and Krakauer's - what would make you think Krakauer was in a better position to judge?

This was not the only time that I got to doubt the sincerity of the author. In fact, there were numerous moments throughout the book when I wanted to ring the BS bell.

At one point, Krakauer dismisses several psychological theories that sought to explain McCandless' behaviour. I admit that the theories he mentions sounded far-fetched and seemed to be based on long-disproved Freudian models, but for Krakauer to follow this up with a theory of his own was just extraordinarily arrogant. The aspect of Krakauer's theory that I found particularly vexing was that he tried to sell it on the premise that he, Krakauer, had a deeper understanding of McCandless' frame of mind because he was a mountaineer who could relate to the excitement of facing physical challenges and the mental struggle of keeping it together under harsh conditions. Blah, blah, blah.

What Krakauer does achieve is to conveniently slip in some stories of his own exploits - which have nothing to do with McCandless' story. If ever there was an inappropriate time for self-promotion, this was it.

There was also a point where Krakauer implied that the author of a book on ethnobotany found in McCandless' possession was to blame for his death because she failed to point out in the book that certain seeds were poisonous.

And if this example was not enough, he managed to top this by constantly comparing McCandless' story to that of other adventurers who met with rather sticky ends. Most of these stories were, again, rather unrelated to McCandless. I'm still puzzled why Krakauer thought it would be appropriate to compare McCandless' story to that of the Franklin expedition and go off on a tangent about how Franklin condemned his men to death because of his (Franklin's) stupidity and lack of respect of nature - which is also much unsubstantiated conjecture on Krakauer's part. But who will argue with a self-appointed expert who does not need to cite sources?

In the end, I got the feeling that Krakauer had an agenda in writing this book that tried to make more of McCandless' story than there really was.

In my mind, McCandless was young guy who made a choice and - tragically and fatally for him - it didn't work out. However, there was no conspiracy. There was no one to blame. There also was no dramatic heroism other than that of a guy trying to live as he saw fit. Other than that, we will never know, but this also seemed to have been part of McCandless' plan.

"In 1992, however, there were no more blank spots on the map - not in Alaska, not anywhere. But Chris, with his idiosyncratic logic, came up with an elegant solution to this dilemma: He simply got rid of the map. In his own mind, if nowhere else, the terra would thereby remain incognita." .

Edit - 28.10.15: I corrected some typos.

Reading updates

- Started reading

- 25 October, 2015: Finished reading

- 25 October, 2015: Reviewed