Reviewed by Briana @ Pages Unbound on

Beyond her fairly normal boy obsession, a lot of Casey’s life is unbelievable—and not just because she happens to travel in time. It is the mechanics of this that come across as a bit sketchy. For one thing, she poofs around a lot, from the present to the past and back to the present again. Eventually it is explained that she appears back in the same moment in the present, so her “absence” should not be too noticeable, but later she seems to worry about this and other things that supposedly were not a problem before. The best bet is to ignore these small inconsistencies if possible.

The portrayal of the past also oscillates from good to okay. At times the 1860s are quite believable. At other times, the characters’ speech sounds unfortunately stilted, and Casey does things that she probably should not be allowed to do. Usually the native nineteenth-century dwellers tell Casey her plans are unseemly for a young woman, but they offer a few solutions that actually seem equally questionable. Yes, Casey should not walk around alone at night near a tavern, but is it much better for her to be riding a horse by herself with a black man? Strauss has the generalities of the time period down, and maybe my own knowledge of history tends to the general, but the book seems as though it could have achieved just a little more if a Civil War expert had gone through it.

The discussion of the implications of Casey’s time travel is where Strauss actually shines on the subject. In the beginning, it does not seem as though Casey thinks much about this, and her persistence in shouting down the injustices toward blacks and women in the nineteenth century is mildly annoying (because most readers agree with her and do not need the lecture). However, she eventually makes this intriguing statement: “I used to think that maybe I’m here to try to fix an injustice, undo an evil, but then I figured maybe I could just end up setting the course for an even greater injustice.” At the point this quote shows up, it is almost unexpectedly profound. But once it does, the book goes on to at least briefly address a few more serious issues, such as adoption, abortion, and guilt and redemption.

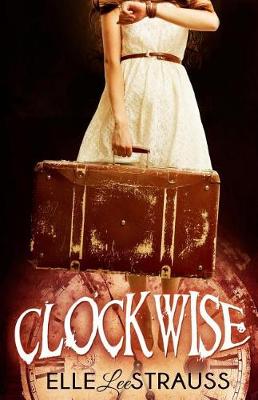

Clockwise starts out a lighthearted and just a little bit fluffy, and it retains its sense of whimsy and Casey’s creative outlooks throughout the whole book. But somewhere in all the fun, Strauss has some interesting things to say about purpose and life, and that combination makes it a worthwhile read.

This review was also posted at Pages Unbound Book Reviews.

Reading updates

- Started reading

- 11 January, 2012: Finished reading

- 11 January, 2012: Reviewed