Reviewed by Amber (The Literary Phoenix) on

Erika Janik seems to me like the type of person who learns a fact, then gets really excited about it and learns everything possible about the subject. She is clearly enthusiastic and while I found Pistols and Petticoats interesting, it was a little too ambitious and scattered for my tastes.

There are several ways to format any non-fiction work. My experience in historical works is that they are approached from a chronological point-of-view. Janik, instead, chooses to take the route of division of subject matter. There are chapters about the first women in real life and fiction, there are chapters about uniforms and dress, job requirements, the social stigmas of being in law enforcement and so forth. If I were a researcher looking for a specific body of information, this would be quite useful. From a read-through standpoint, however, it makes the work feel scattered. Names come up time and again and are not always reintroduced so I would have to keep jumping back to figure out who she was talking about.

Speaking of names, there are a lot of them. Tackling both real-world women and fictional ones, and their authors is a fairly ambitious topic for so small a book and there are a lot of condensed facts. If anything, I would have advised breaking this work into three separate sections and tackling each angle one at a time, just for the reader’s sake. Having to go back and fact check on fictional vs. real life women definitely disrupted the flow.

Detail is something Janik offers in spades. It is immediately clear how passionate she is about her subject, and her desire to share every little bit of what she has learned. There is absolutely nothing vague about her work – you want detail? You got it.

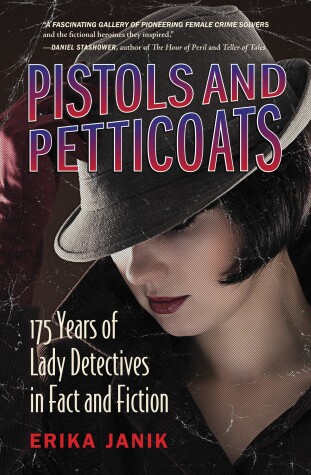

Women in law enforcement is an interesting subject and I do appreciate how Janik has tried to offer even more illumination by wrangling the likes of Miss Marple and Nancy Drew into the mix. I think I was more interested in the history of female detectives in fiction than I was in the real life women, although the included image section in the middle of the book was a nice touch. I never knew, for example, that L. Frank Baum had written a series of adventuring women. I don’t know how thoroughly this subject has been approached before, or if there are any other books quite like this one, but Janik’s passion certainly presents an interesting subject.

I think there are about twenty pages of source material and references in the appendix of this book, and all are great for those who found this book interesting, but wanted to dive more deeply into a singular section of the material – women’s treatment in prisons, for example. Janik is very well researched.

Overall, I just wasn’t blown away by this book. I will not deny that Janik knows her source material and knows it well, and the subject is interesting… but I found the readability very difficult for me. I know this isn’t always evident from my blog and reviews on Goodreads, but I have ready a fair amount of historical non-fiction and don’t attribute the difficulty in reading this to a change in flow from fiction to non-fiction. In fact, I find that formats like this are the types that steer laymen away from history – there are so many names and dates and not a clear lineage of growth of the story (and yes, historical non-fiction definitely has a story). Pistols and Petticoats is a fine book for academics to pick up and peruse, but it may be less accessible to those unprepared to jump into a lot of scattered detail.

First posted on The Literary Phoenix

Reading updates

- Started reading

- 16 July, 2017: Finished reading

- 16 July, 2017: Reviewed