The German List - (Seagull Titles CHUP)

5 total works

In the historic tradition of calendar stories and calendar illustrations, author and film director Alexander Kluge and celebrated visual artist Gerhard Richter have composed "December", a collection of thirty-nine stories and thirty-nine snow-swept photographs for the darkest month of the year. In stories drawn from modern history and the contemporary moment, from mythology, and even from meteorology, Kluge toys as readily with time and space as he does with his characters. In the narrative entry for December 1931, Adolf Hitler avoids a car crash by inches. In another, we relive Greek financial crises. There are stories where time accelerates, and others in which it seems to slow to the pace of falling snow. In Kluge's work, power seems only to erode and decay, never grow, and circumstances always seem to elude human control. When a German commander outside Moscow in December of 1941 remarks, "We don't need weapons to fight the Russians but a weapon to fight the weather," the futility of his struggle is painfully present.

Accompanied by the ghostly and wintry forest scenes captured in Gerhard Richter's photographs, these stories have an alarming density, one that gives way at unexpected moments to open vistas and narrative clarity. Within these pages, the lessons are perhaps not as comforting as in the old calendar stories, but the subversive moralities are always instructive and perfectly executed.

Accompanied by the ghostly and wintry forest scenes captured in Gerhard Richter's photographs, these stories have an alarming density, one that gives way at unexpected moments to open vistas and narrative clarity. Within these pages, the lessons are perhaps not as comforting as in the old calendar stories, but the subversive moralities are always instructive and perfectly executed.

Max Weber famously described politics as "a strong, slow drilling through hard boards with both passion and judgment." Taking this as his inspiration, Alexander Kluge brings readers yet another literary masterpiece. Drilling through Hard Boards is a kaleidoscopic meditation on the tools available to those who struggle for power. Weber's metaphorical drill certainly embodies intelligent tenacity as a precondition for political change. But what is a hammer in the business of politics, Kluge wonders, and what is a subtle touch? Eventually, we learn that all questions of politics lead to a single one: what is political in the first place? In the book, Kluge masterfully unspools more than one hundred vignettes, through which it becomes clear that the political is more often than not personal. Politics are everywhere in our everyday lives, so along with the stories of major political figures, we also find here the small, mostly unknown ones: Elfriede Eilers alongside Pericles, Chilean miners next to Napoleon, a three-month-old baby beside Alexander the Great. Drilling through Hard Boards is not just Kluge's newest fiction, it is a masterpiece of political thought.

On October 5, 2012, the German national newspaper Die Welt published its daily issue—but things looked . . . different. Quieter. The sensations of the day, forgotten as soon as they’re read, were missing, replaced with an unprecedented calm, extracted with care from the chaos of the contemporary.

That calm was the work of Gerhard Richter, who had been granted control over Die Welt for that single day, taking over and imprinting all thirty pages of the newspaper with his personal stamp: images from quiet moments amid unquiet times, the demotion of politics from its primary position, the privileging of the private and personal over the public, and, above all, artful, moving contrasts between sharpness and softness. He had created an unprecedented work of mass art.

Among the many people to praise the work was writer Alexander Kluge, who instantly began writing stories to accompany Richter’s images. This book, the second collaboration between Kluge and Richter, brings their stories and images together, along with new words and artworks created specifically for this volume. The result, Dispatches from Moments of Calm, is a beautiful, meditative interval in the otherwise unremitting press of everyday life, a masterpiece by two acclaimed artists working at the height of their powers.

That calm was the work of Gerhard Richter, who had been granted control over Die Welt for that single day, taking over and imprinting all thirty pages of the newspaper with his personal stamp: images from quiet moments amid unquiet times, the demotion of politics from its primary position, the privileging of the private and personal over the public, and, above all, artful, moving contrasts between sharpness and softness. He had created an unprecedented work of mass art.

Among the many people to praise the work was writer Alexander Kluge, who instantly began writing stories to accompany Richter’s images. This book, the second collaboration between Kluge and Richter, brings their stories and images together, along with new words and artworks created specifically for this volume. The result, Dispatches from Moments of Calm, is a beautiful, meditative interval in the otherwise unremitting press of everyday life, a masterpiece by two acclaimed artists working at the height of their powers.

On April 8, 1945, several American bomber squadrons were informed that their German targets were temporarily unavailable due to cloud cover. As it was too late to turn back, the assembled ordnance of more than two hundred bombers was diverted to nearby Halberstadt. A midsized cathedral town of no particular industrial or strategic importance, Halberstadt was almost totally destroyed, and a then-thirteen-year-old Alexander Kluge watched his town burn to the ground. Translated by Martin Chalmers, Kluge's Air Raid is a touchstone event in German literature of the postwar era. Incorporating photographs, diagrams, and drawings, Kluge captures the overwhelming rapidity and totality of the organized destruction of his town from numerous perspectives, bringing to life both the strategy from above and the futility of the response on the ground. Originally published in German in 1977, this exquisite report, fragmentary and unfinished, is one of Kluge's most personal works and one of the best examples of his literary technique. Now available for the first time in English, Air Raid appears with additional new stories by the author and features an appreciation of the work by W. G. Sebald.

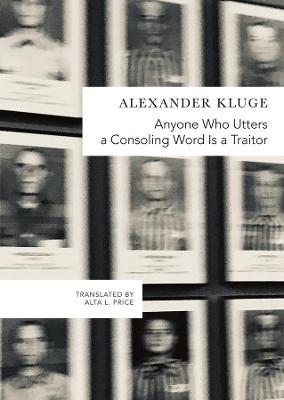

A book about bitter fates—both already known and yet to unfold—and the many kinds of organized machinery built to destroy people.

Alexander Kluge’s work has long grappled with the Third Reich and its aftermath, and the extermination of the Jews forms its gravitational center. Kluge is forever reminding us to keep our present catastrophes in perspective—“calibrated”—against this historical monstrosity. Kluge’s newest work is a book about bitter fates, both already known and yet to unfold. Above all, it is about the many kinds of organized machinery built to destroy people. These forty-eight stories of justice and injustice are dedicated to the memory of Fritz Bauer, a determined fighter for justice and district attorney of Hesse during the Auschwitz Trials. “The moment they come into existence, monstrous crimes have a unique ability,” Bauer once said, “to ensure their own repetition.” Kluge takes heed, and in these pages reminds us of the importance of keeping our powers of observation and memory razor sharp.

Alexander Kluge’s work has long grappled with the Third Reich and its aftermath, and the extermination of the Jews forms its gravitational center. Kluge is forever reminding us to keep our present catastrophes in perspective—“calibrated”—against this historical monstrosity. Kluge’s newest work is a book about bitter fates, both already known and yet to unfold. Above all, it is about the many kinds of organized machinery built to destroy people. These forty-eight stories of justice and injustice are dedicated to the memory of Fritz Bauer, a determined fighter for justice and district attorney of Hesse during the Auschwitz Trials. “The moment they come into existence, monstrous crimes have a unique ability,” Bauer once said, “to ensure their own repetition.” Kluge takes heed, and in these pages reminds us of the importance of keeping our powers of observation and memory razor sharp.