Vintage International

5 total works

As a novice reporter in the 1950s, the young Ryzsard Kapuscinski wanted nothing more than to travel outside the borders of Poland. One day, without warning, his editor called him into her office and told him he was being sent to India. `At the end of our conversation, during which I learned that I would indeed be going forth into the world, Tarlowska reached into a cabinet, took out a book, and handing it to me said "Here, a present for the road." It was a thick book with a stiff cover of yellow cloth. On the front, stamped in gold letters, was Herodotus' The Histories.'

Travels with Herodotus records how Kapuscinski set out on his first forays - to India, China and Africa - with the great Greek historian constantly in his pocket. He sees Louis Armstrong in Khartoum, visits Dar-es-Salaam, arrives in Algiers in time for a coup when nothing seems to happen (but he sees the Mediterranean for the first time). At every encounter with a new culture, Kapuscinski plunges in, curious and observant, thirsting to understand its history, its thought, its people. And he reads Herodotus so much that he often feels he is embarking on two journeys - the first his assignment as a reporter, the second following Herodotus' expeditions.

Woven into his accounts of his travels are his retellings of Herodotus' epic stories. His whole life as a reporter is a dialogue with what he calls `world literature's first great work of reportage.' What kind of restless, enquiring traveller was its author? he asks. `Man is by nature a sedentary creature, settled down happily, naturally, on his particular patch of earth ... But to traverse the world for years in order to get to know it, to plumb it, to understand it? And then, later, to put all his findings into words? Such people have always been uncommon.'

How right, and how satisfying, that those words should be among the last written by Ryszard Kapuscinski, the greatest traveller-reporter of our time.

Travels with Herodotus records how Kapuscinski set out on his first forays - to India, China and Africa - with the great Greek historian constantly in his pocket. He sees Louis Armstrong in Khartoum, visits Dar-es-Salaam, arrives in Algiers in time for a coup when nothing seems to happen (but he sees the Mediterranean for the first time). At every encounter with a new culture, Kapuscinski plunges in, curious and observant, thirsting to understand its history, its thought, its people. And he reads Herodotus so much that he often feels he is embarking on two journeys - the first his assignment as a reporter, the second following Herodotus' expeditions.

Woven into his accounts of his travels are his retellings of Herodotus' epic stories. His whole life as a reporter is a dialogue with what he calls `world literature's first great work of reportage.' What kind of restless, enquiring traveller was its author? he asks. `Man is by nature a sedentary creature, settled down happily, naturally, on his particular patch of earth ... But to traverse the world for years in order to get to know it, to plumb it, to understand it? And then, later, to put all his findings into words? Such people have always been uncommon.'

How right, and how satisfying, that those words should be among the last written by Ryszard Kapuscinski, the greatest traveller-reporter of our time.

In Shah of Shahs Kapuscinski brings a mythographer's perspective and a novelist's virtuosity to bear on the overthrow of the last Shah of Iran, one of the most infamous of the United States' client-dictators, who resolved to transform his country into "a second America in a generation," only to be toppled virtually overnight. From his vantage point at the break-up of the old regime, Kapuscinski gives us a compelling history of conspiracy, repression, fanatacism, and revolution.Translated from the Polish by William R. Brand and Katarzyna Mroczkowska-Brand.

'This is a very personal book, about being alone and lost'. In 1975 Kapuscinski's employers sent him to Angola to cover the civil war that had broken out after independence. For months he watched as Luanda and then the rest of the country collapsed into a civil war that was in the author's words 'sloppy, dogged and cruel'. In his account, Kapuscinski demonstrates an extraordinary capacity to describe and to explain the individual meaning of grand political abstractions.

'Only with the greatest of simplifications, for the sake of convenience, can we say Africa. In reality, except as a geographical term, Africa doesn't exist'. Ryszard Kapuscinski has been writing about the people of Africa throughout his career. In astudy that avoids the official routes, palaces and big politics, he sets out to create an account of post-colonial Africa seen at once as a whole and as a location that wholly defies generalised explanations. It is both a sustained meditation on themosaic of peoples and practises we call 'Africa', and an impassioned attempt to come to terms with humanity itself as it struggles to escape from foreign domination, from the intoxications of freedom, from war and from politics as theft.

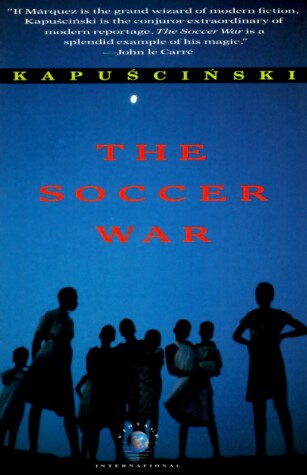

Part diary and part reportage, The Soccer War is a remarkable chronicle of war in the late twentieth century. Between 1958 and 1980, working primarily for the Polish Press Agency, Kapuscinski covered twenty-seven revolutions and coups in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. Here, with characteristic cogency and emotional immediacy, he recounts the stories behind his official press dispatches—searing firsthand accounts of the frightening, grotesque, and comically absurd aspects of life during war. The Soccer War is a singular work of journalism.