Master Drawings

1 total work

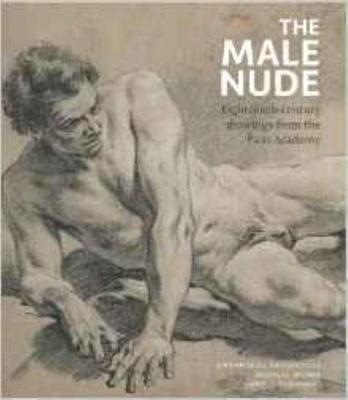

The Male Nude

by Camille Debrabant, George Brunel, and Emmanuelle Brugerolles

Published 3 October 2013

Painting in 18th-century France was centred on the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris, where the drawing of the male human figure was at the core of the curriculum. Only after mastering the copying of drawings and engravings, and then casts of antique sculptures, would the student be allowed to progress to drawing the nude figure in the life class. The drawings produced there were so associated with the Academy that they came to be known as "académies".

Accompanying a groundbreaking exhibition at the Wallace Collection, this publication includes remarkable drawings by Rigaud, Boucher, Nattier, Pierre, Carle van Loo, Gros, and Jean-Baptiste Isabey. Variety and beauty are omnipresent. The works show figures - sometimes single, sometimes two together - in an enormous variety of poses and in various degrees of light and shade. The study of physiognomic expression was also taught at the Academy, and the facial expressions of the figures always complement the poses they adopt, whether they show serenity, exertion, pleasure, or anger.

The catalogue of over 40 masterpieces from the Academy collection - now belonging to theÉcole des Beaux-arts - is introduced with three essays by distinguished scholars. Emmanuelle Brugerolles and Camille Debrebant write about the teaching methods at the Academy, to which no female artists were admitted and all models were male. (This practice in itself went on to create problems for artists, who, lacking the necessary training to portray the female form, were compelled to search out models, not always in the most respectable settings.) They consider the complete collection of 600 drawings made over a period of some 150 years. Exceptional in its size and consistency, the Beaux-arts collection remains an extraordinary testimony to teaching methods and artistic doctrines that, though they are no longer current, still offer food for thought.

Georges Brunel's essay, 'Art and Manner', highlihgts some features of the artistic doctrine, which, while remaining stable for a century and a half, from 1650 to 1800, was nevertheless modified over time, each period reflecting its own sense of form and artistic expectations. The foundation of academic teaching in the imitation of nature, the quest for beauty, and the study of the Antique did not change. But these notions can all be interpreted in many different ways. Is nature simply what is there to be seen, does beauty lie in the faithful reproduction of what is seen, does the Antique constitute the ultimate artistic reference point and touchstone of artistic merit and, ultimately, can there be art without"manner"?

Accompanying a groundbreaking exhibition at the Wallace Collection, this publication includes remarkable drawings by Rigaud, Boucher, Nattier, Pierre, Carle van Loo, Gros, and Jean-Baptiste Isabey. Variety and beauty are omnipresent. The works show figures - sometimes single, sometimes two together - in an enormous variety of poses and in various degrees of light and shade. The study of physiognomic expression was also taught at the Academy, and the facial expressions of the figures always complement the poses they adopt, whether they show serenity, exertion, pleasure, or anger.

The catalogue of over 40 masterpieces from the Academy collection - now belonging to theÉcole des Beaux-arts - is introduced with three essays by distinguished scholars. Emmanuelle Brugerolles and Camille Debrebant write about the teaching methods at the Academy, to which no female artists were admitted and all models were male. (This practice in itself went on to create problems for artists, who, lacking the necessary training to portray the female form, were compelled to search out models, not always in the most respectable settings.) They consider the complete collection of 600 drawings made over a period of some 150 years. Exceptional in its size and consistency, the Beaux-arts collection remains an extraordinary testimony to teaching methods and artistic doctrines that, though they are no longer current, still offer food for thought.

Georges Brunel's essay, 'Art and Manner', highlihgts some features of the artistic doctrine, which, while remaining stable for a century and a half, from 1650 to 1800, was nevertheless modified over time, each period reflecting its own sense of form and artistic expectations. The foundation of academic teaching in the imitation of nature, the quest for beauty, and the study of the Antique did not change. But these notions can all be interpreted in many different ways. Is nature simply what is there to be seen, does beauty lie in the faithful reproduction of what is seen, does the Antique constitute the ultimate artistic reference point and touchstone of artistic merit and, ultimately, can there be art without"manner"?