Casemate Illustrated Special

2 total works

World War I witnessed unprecedented growth and innovation in aircraft design, construction, and as the war progressed - mass production. Each country generated its own innovations sometimes in surprising ways - Albatros Fokker, Pfalz, and Junkers in Germany and Nieuport, Spad, Sopwith and Bristol in France and Britain.

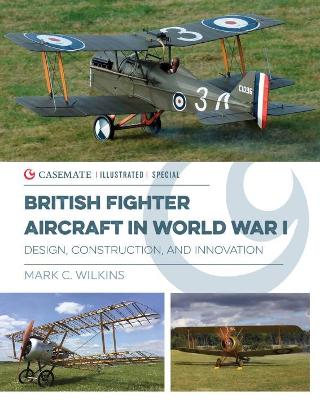

This book focuses on the British approach to fighter design, construction, and mass production. Initially the French led the way in Allied fighter development with their Bleriot trainers then nimble Nieuport Scouts - culminating with the powerful, fast gun platforms as exemplified by the Spads. The Spads had a major drawback however, in that they were difficult and counter-intuitive to fix in the field. The British developed fighters in a very different way; Tommy Sopwith had a distinctive approach to fighter design that relied on lightly loaded wings and simple functional box-girder fuselages. His Camel was revolutionary as it combined all the weight well forward; enabling the Camel to turn very quickly - but also making it an unforgiving fighter for the inexperienced. The Royal Aircraft Factory's SE5a represented another leap forward with its comfortable cockpit, modern instrumentation, and inline engine - clearly influenced by both Spads and German aircraft.

Each manufacturer and design team vied for the upper hand and deftly and quickly appropriated good ideas from other companies – be they friend or foe. Developments in tactics and deployment also influenced design - from the early reconnaissance planes, to turn fighters, finally planes that relied upon formation tactics, speed, and firepower. Advances were so great that the postwar industry seemed bland by comparison.

This book focuses on the British approach to fighter design, construction, and mass production. Initially the French led the way in Allied fighter development with their Bleriot trainers then nimble Nieuport Scouts - culminating with the powerful, fast gun platforms as exemplified by the Spads. The Spads had a major drawback however, in that they were difficult and counter-intuitive to fix in the field. The British developed fighters in a very different way; Tommy Sopwith had a distinctive approach to fighter design that relied on lightly loaded wings and simple functional box-girder fuselages. His Camel was revolutionary as it combined all the weight well forward; enabling the Camel to turn very quickly - but also making it an unforgiving fighter for the inexperienced. The Royal Aircraft Factory's SE5a represented another leap forward with its comfortable cockpit, modern instrumentation, and inline engine - clearly influenced by both Spads and German aircraft.

Each manufacturer and design team vied for the upper hand and deftly and quickly appropriated good ideas from other companies – be they friend or foe. Developments in tactics and deployment also influenced design - from the early reconnaissance planes, to turn fighters, finally planes that relied upon formation tactics, speed, and firepower. Advances were so great that the postwar industry seemed bland by comparison.

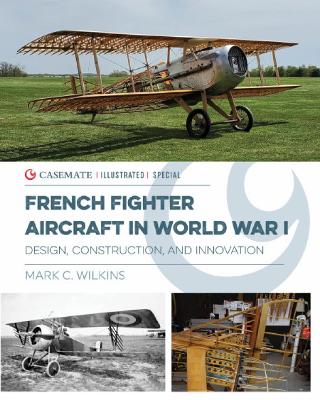

During the first decade of the 20th century, France led the way in aircraft design and achievements. After the outbreak of World War I, France produced trailblazing designs early – the Morane Saulnier monoplanes, Nieuport fighters, and then the Spads – clearly leading the way in terms of trends in aviation. Although the Fokker Eindeckers were the first 'point and shoot' aircraft, the Nieuport 11, while lacking interrupter gear, was the first maneuverable and cleanly designed fighter that featured ailerons and responsive controls on all axes. The Nieuports were so successful that Germany co-opted the sesquiplane with their Albatros line of fighters. The Spad VII was the first Allied fighter to employ an inline engine, and by extension influenced the design path of the S.E.5a and the Dolphin. French construction methodology was eclectic – the Nieuports were straightforward in their construction, as were the British, but the Spad was a labor-intensive yet rugged and finely built aircraft – requiring many different skill sets to produce. Moreover, Spads were built under license by many companies in France as well as in Britain. Finally, French engines were in demand for not only their own aircraft, but for much of the British aviation industry as well. This fully illustrated book will complement the author’s titles on the German and French fighter aircraft.