Graeco-Roman Memoirs

2 primary works

Book 94

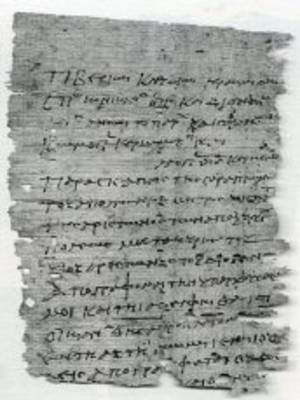

This volume publishes a selection of texts prepared to highlight recent work on the "Oxyrhynchus Collection" in Part I, papyri of the Old and New Testaments. Part II offers "Comedy Old and New: Aristophanes", a sizeable chunk of Menander's Epitrepontes and another from his Georgos. Part III presents previously unknown Greek literature, including a new papyrus of Empedocles; a work by Thrasyllus (Tiberius' court astrologer and philosopher in residence) on the classification of Plato's dialogues - together with Dictys of Crete's account of the Trojan War in unpretentious prose, complete with its 'author's' own subscription. These add two new papyri of the Greek original to the two already known. They show more clearly the relation of the Greek original to the Latin version, casting doubt on the status of the letter as a straightforward translation. In 4939, a distraught lover laments his girlfriend's untimely passing at considerable length in hexameter verse. A glimpse of the sleek, dark underbelly of Greek culture is afforded by a slice of Lollianos' novel "Phoinikika"; a fragment of Hellenistic history may be the earliest textual attestation of the histories of Timagenes.

Part IV showcases texts of previously known Greek literature of the Roman period uncommon among the papyri, while Part V presents texts at the subliterary level. On the documentary side, in part VI we find themes of extortion in petitions; a military muster, in Latin; a letter on recovery from illness in high-flown Greek; a certified copy of a petition to a prefect, which besides its impressive format has interesting though enigmatic implications for the use of Roman Law. 4965 is a Manichaean letter. 4956 is a census declaration, written in a standard scribal book-hand; 4967 contains a new but unread notarial signature. In 4966 we get what is possibly the first Egyptian member of the senate at Constantinople; and in 4967 the terms of employment of a public herald.

Part IV showcases texts of previously known Greek literature of the Roman period uncommon among the papyri, while Part V presents texts at the subliterary level. On the documentary side, in part VI we find themes of extortion in petitions; a military muster, in Latin; a letter on recovery from illness in high-flown Greek; a certified copy of a petition to a prefect, which besides its impressive format has interesting though enigmatic implications for the use of Roman Law. 4965 is a Manichaean letter. 4956 is a census declaration, written in a standard scribal book-hand; 4967 contains a new but unread notarial signature. In 4966 we get what is possibly the first Egyptian member of the senate at Constantinople; and in 4967 the terms of employment of a public herald.

Book 104

Volume LXXXIII of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri continues our publication of biblical texts, including what is only the second Egyptian witness to the Epistle of Philemon as well as further early witnesses to the text of Mark and Luke, and an amateur copy of excerpts from Ezekiel's Exagoge. Other sections offer new fragments from two popular genres: trials from the Acta Alexandrinorum, notably the trial of the former Prefect Titianus before Hadrian (an event sensational enough to reach the Historia Augusta); and adventures from the Greek Novel, including the Crimean narrative of Calligone and the Amazons. There is also a glimpse of the anonymous copyists to whom we owe our texts, practising the various graphic styles from which their customers could choose. Other documents contribute a mass of detail to the social and economic history of Roman and Byzantine Egypt, such as an official letter about the tax-grain destined to supply Rome; a tax-receipt that attests a Jewish community at Oxyrhynchus in the late fourth century; and, quite an extraordinary object, part of a ceremonial painted with a laurel wreath and a Latin inscription that celebrates the twentieth anniversary of some fourth-century emperor. The final section of the volume contains art: a fine pen-and-ink drawing of a rampant goat, and seven sketches on a single sheet, including a cockerel and a peacock, a wild boar, and a unicorn. As the Artemidorus papyrus has renewed discussion of drawing as an art in the Greek world, with some finding its own spread of drawings so striking as to suggest forgery, the new examples from Oxyrhynchus now demonstrate comparable technique and similar subject-matter in papyri of undoubted authenticity.