Helion Studies in Military History

2 total works

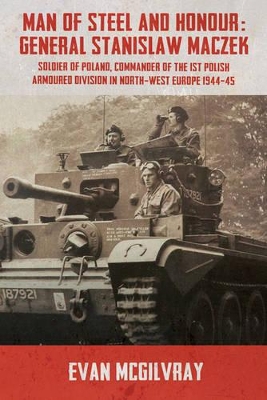

This is a biography of one of the most undervalued commanders of the Second World War, General Stanislaw Maczek, a soldier overlooked by most military historians in the West both because he was Polish and above politics. Unlike most Polish commanders he rocked no boats and after his service was complete in 1947 he retreated into relative obscurity. When he died at the age of 102 he had left a single published book of his war memoirs and little else to the popular imagination. One had to be acquainted with his armoured division, the wartime 1st Polish Armoured Division in order to know anything of the man or even to have even heard of him. This book is an attempt to try to put the historical record right, at least in the English language, and place front and centre into the wartime historiography the story of an extraordinary man.

Maczek's story is the story of 20th Century Poland and begins naturally enough with his birth in 1892, into a Poland that hadn't existed since 1795 when it was trisected between the three empires of Austrian, Russia and Prussia (later Germany). Maczek was born in the Austrian sector, which meant in 1914 he was conscripted into the Imperial Austrian Army, with which he served with great credit on the Italian Front, high in the Alps. It was this experience which was to serve Maczek well in his future career in the Polish Army after 1918. / Maczek should be remembered for his pioneering use of mixed armour and infantry units as well as the early use of commando-style units during the Polish border wars of 1918-1920. However his work was ignored despite its obvious success. He should also be recognised as being the saviour of the Normandy Campaign, which by August 1944 was seriously bogged down. It was feared that the German forces in Normandy might be able to flee over the River Seine and head eastwards towards Germany. A magnificent, stubborn and costly stand by the Polish 1st Armoured Division during August 1944 prevented this happening, and the Normandy Campaign was able to succeed. This is yet to be credited to the Poles in the imagination of the West. Maczek's division was later able to advance into Germany, fighting its way through the Low Countries. Maczek's command of the division and its combat service in North-West Europe 1944-45 is fully described, and represents, in particular, an important contribution to our knowledge of the Normandy Campaign.

After the war, Maczek, now exiled and stateless and with his homeland seized by the Soviet Union, was stripped of his Polish citizenship by the Communists, and was left to bring up his young family on his wages as a barman. This is the story of a man who changed history, fully researched from archival and printed materials, and with a heavy reliance on original Polish language sources. The text is complemented by over 100 previously unpublished photographs, focusing on Maczek and the 1st Polish Armoured Division 1944-45.

Maczek's story is the story of 20th Century Poland and begins naturally enough with his birth in 1892, into a Poland that hadn't existed since 1795 when it was trisected between the three empires of Austrian, Russia and Prussia (later Germany). Maczek was born in the Austrian sector, which meant in 1914 he was conscripted into the Imperial Austrian Army, with which he served with great credit on the Italian Front, high in the Alps. It was this experience which was to serve Maczek well in his future career in the Polish Army after 1918. / Maczek should be remembered for his pioneering use of mixed armour and infantry units as well as the early use of commando-style units during the Polish border wars of 1918-1920. However his work was ignored despite its obvious success. He should also be recognised as being the saviour of the Normandy Campaign, which by August 1944 was seriously bogged down. It was feared that the German forces in Normandy might be able to flee over the River Seine and head eastwards towards Germany. A magnificent, stubborn and costly stand by the Polish 1st Armoured Division during August 1944 prevented this happening, and the Normandy Campaign was able to succeed. This is yet to be credited to the Poles in the imagination of the West. Maczek's division was later able to advance into Germany, fighting its way through the Low Countries. Maczek's command of the division and its combat service in North-West Europe 1944-45 is fully described, and represents, in particular, an important contribution to our knowledge of the Normandy Campaign.

After the war, Maczek, now exiled and stateless and with his homeland seized by the Soviet Union, was stripped of his Polish citizenship by the Communists, and was left to bring up his young family on his wages as a barman. This is the story of a man who changed history, fully researched from archival and printed materials, and with a heavy reliance on original Polish language sources. The text is complemented by over 100 previously unpublished photographs, focusing on Maczek and the 1st Polish Armoured Division 1944-45.

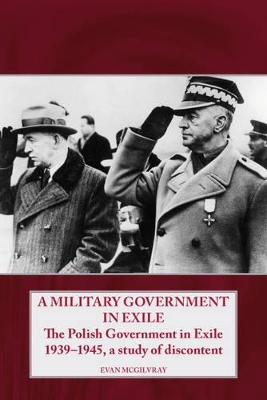

This work examines the nature of the relationship between the British Government and the Polish Government-in-Exile, 1939-1945. The relationship was extremely difficult owing to the extremity of the time and the situations of the two governments. Before 1939 there had been little contact between Poland and Britain, however between 1939 and 1945 the two countries were joined in a common desire for the military defeat of Germany: this was virtually the only common goal that the two governments shared; Polish ambitions to see Poland restored to its pre-war frontiers were not shared with its major allies (Britain, the USA and the Soviet Union) after 1941.

The question of differing objectives caused friction between the Western allies, the Soviet Union and the Polish Government-in-Exile. The Polish Government-in-Exile failed to recognise its true position in the alliance: it was very much a junior partner - just another minor European power and irritant. A key problem in the relationship between the British Government and the Polish Government-in-Exile was bound up in the lack of democracy present in the latter. Between 1926 and 1939 Poland had been ruled by a military clique and the signs were that little had changed in the mindset of many Poles, especially those military officers who arrived in exile after 1939. This situation vexed the British Government, which sought to work with democratically minded Poles, but found this pool to be limited owing to the continuing political influence of the Polish military in exile. This attitude worsened as the war progressed until eventually the Polish Government-in-Exile lost any relevance in the war against Germany.

The question of differing objectives caused friction between the Western allies, the Soviet Union and the Polish Government-in-Exile. The Polish Government-in-Exile failed to recognise its true position in the alliance: it was very much a junior partner - just another minor European power and irritant. A key problem in the relationship between the British Government and the Polish Government-in-Exile was bound up in the lack of democracy present in the latter. Between 1926 and 1939 Poland had been ruled by a military clique and the signs were that little had changed in the mindset of many Poles, especially those military officers who arrived in exile after 1939. This situation vexed the British Government, which sought to work with democratically minded Poles, but found this pool to be limited owing to the continuing political influence of the Polish military in exile. This attitude worsened as the war progressed until eventually the Polish Government-in-Exile lost any relevance in the war against Germany.