The Fonthill Complete A. G. Macdonell

7 total works

The Autobiography of a Cad is a hilarious mock memoir of the life and times of one Edward Fox-Ingleby. It ranges from his earliest memories of his father's Midlands estate, through Eton, Oxford, and the Great War, to his defining moment: his installation as a Tory minister in the 1930s. A rotter and a chancer of the first order, Fox-Ingleby will do anything to get what he wants--power, money, and of course, lashings of the fairer sex. His memoir, an attempt to legitimize his detestable life, is prone to bouts of grand prolix and riddled with misogyny, bigotry, and more than the odd sleight of hand. Turning a perpetually blind eye to his devious and malicious acts, Fox-Ingleby chooses instead to portray himself as a gentleman misunderstood. But this despicable cad is always just one step away from having his Machiavellian plots uncovered, making this a marvelous tale of seedy intrigue.

In 1934, at the peak of the Great Depression, A. G. Macdonell embarked on a journey across America. This travelogue is the deliciously scathing product of that adventure: a vivid and unflinchingly honest record of life in the cities and the slums, on the roads, railways, and the vast open plains. "The hot breath of the Apocalyptic Horsemen is on my neck, and I still wake up on occasions in peaceful England, cold with terror from the dream that I am once again upon the road." By the time he departed for America, Macdonell was an international celebrity, and as such, he was afforded a privileged glimpse into both the glamour and the gritty reality of 1930s America. With brutal humour he glides effortlessly between lavish dinners and dances at the Plaza Hotel, passionate football games comparable to the 'less pleasing features' of the First World War, and the humbling 'Spirit of the Pioneers' buried deep within the poverty-stricken cattle ranges of Montana. While his descriptions can be savage and mocking, Macdonell is also affectionate, compassionate, and startlingly insightful.In A Visit to America, he gamely captures all that is beautiful and repulsive about a country gripped in economic turmoil; fascinating and timeless, it is an indulgence not to be missed.

A fascinating thrill with unusual twists - a 'Buchanesque' tale Writing under the pseudonym Neil Gordon, A. G. Macdonell wrote several crime and thriller novels. In the classic genre of '20s and '30s crime fiction, Macdonell managed to introduce a different element, unusual twists that keep the reader captivated and anxious to discover what came next. The Factory on the Cliff begins with a spoilt golf holiday at a coastal golf-links hotel in Aberdeenshire. 'George Templeton's car refused to start on the self-starter. He jumped out impatiently and gave the handle a mighty twist. The engine back-fired and dislocated his thumb and he found himself unable to play golf for the remainder of his holiday.' Unable to play golf with his friends, he resorts to country walks and stumbles upon suspicious goings-on at a cliff-top farmstead where there are numerous outbuildings. The story moves from Scotland to London, and then to a small village in the Home Counties. In a fast-moving thriller which in some degree resembles John Buchan's The Thirty-Nine Steps, George Templeton and his friends foil an international plot to mass-poison many countries in the World.

Macdonell uses his usual skill, well-dosed with ingenious twists, and a fast moving story-line, to keep the reader riveted to the book. Chase, conspiracy, espionage, quick-thinking initiative and much adventure with Irishmen and Russians thrown in, keeps the adventure in a high gear from beginning to end. New Introduction by Alan Sutton

Macdonell uses his usual skill, well-dosed with ingenious twists, and a fast moving story-line, to keep the reader riveted to the book. Chase, conspiracy, espionage, quick-thinking initiative and much adventure with Irishmen and Russians thrown in, keeps the adventure in a high gear from beginning to end. New Introduction by Alan Sutton

Flight from a Lady is probably Macdonell's most enigmatic works. It is fictional, but hardly reads like a novel. The plot is the story of a very wealthy young man escaping from the clutches of a woman - a woman so determined that the man goes to great lengths to cover his tracks and avoid being trapped by her, the she-wolf. He charters a plane - a Douglas - crewed by a young Dutch charter crew, and off he goes, to France, Italy, Greece, the Middle East and to India. War was looming (the book was published in 1939, just prior to the Second World War) and with his usual prescience Macdonell foretells the future, correctly predicting what was to come. The book is written as if a series of letters, and if were not a novel it would make a wonderful travelogue, for Macdonell, well-educated and well-travelled, makes a good travel narrator. He reminisces on the past, he provides political commentary, and generally uses the loose fabric ofhis novel to voice his pet themes. His reflection on his youthful travels in Germany are an example: It was unfair of us - and we knew it. But we resolutely put the unfairness out of our minds.

The mark tumbled, and the Austrian crown tumbled, and the Hungarian crown tumbled, and we brandished our pound notes and wallowed in the misfortunes of others. We bought their wine for a few pence and their cigars for a farthing and their theatre tickets for an old song, and boasted about it, while they were half-starved and desperately frightened for the future. But they never once reproached us for our profiteering and our arrogance - and never, through all the semi-starvation and the fear, did the sound of laughter entirely die away in the Salzkammergut. It is unbelievable to think of now. In those days we had just finished fighting a bloody war against those very people. We had been trained on Europe's pet curriculum of Hatred. We had been told by innumerable fat sergeant-majors and over-Kummelled major-generals that there was no good Hun except a dead Hun. New introduction by Alan Sutton

The mark tumbled, and the Austrian crown tumbled, and the Hungarian crown tumbled, and we brandished our pound notes and wallowed in the misfortunes of others. We bought their wine for a few pence and their cigars for a farthing and their theatre tickets for an old song, and boasted about it, while they were half-starved and desperately frightened for the future. But they never once reproached us for our profiteering and our arrogance - and never, through all the semi-starvation and the fear, did the sound of laughter entirely die away in the Salzkammergut. It is unbelievable to think of now. In those days we had just finished fighting a bloody war against those very people. We had been trained on Europe's pet curriculum of Hatred. We had been told by innumerable fat sergeant-majors and over-Kummelled major-generals that there was no good Hun except a dead Hun. New introduction by Alan Sutton

For those who have read and enjoyed Macdonell's humorous and affectionate book England Their England, this book, My Scotland, will come as a shock. There are some lighter moments with the occasional flash of the Macdonell genius, but these apart it is a choleric tirade in a style which is not apparent in his other books. At the time of writing he was going through a messy divorce - brought about through his own extra-marital adventures - and this may have added to his mood. He was born in India, brought up in London, educated at Winchester, provided with further excellent character-forming life-experience in France in muddy conditions, and then spent his working life in London. His formal address on his War Record documentation is Bridgefield, Bridge of Don, Aberdeen, but it does not seem that he ever spent a great deal of time in Scotland. Therefore, the spleen and invective coming from someone who adopted England seems out of character. The only explanation is that it came about as the pent-up frustration out of forty years of hearing comments which he viewed as his national heritage being treated as a joke.

From those that knew him he was remembered as a complex individual, 'delightful - but quarrelsome and choleric' (this was by Alec Waugh, who called him the Purple Scot). J. B. Morton (Beachcomber) remembered him as a man of conviction, with a quick wit and enthusiasm and, surprising in a military man, 'a sense of compassion for every kind of unhappiness'. What is surprising, given his depth of knowledge of the English, and the fact that they joke about anything, is that he took it so seriously. Nevertheless, despite Macdonell's exhortations for a 'clamour for independence' towards the end of the book, he did not practice what he preached, and instead of 'leading from the front' by preaching his new gospel from Edinburgh, he remained in England for the remainder of his days. For all those who feel that Scotland has been 'hard-done-by' this is a must-buy book. New introduction by Alan Sutton

From those that knew him he was remembered as a complex individual, 'delightful - but quarrelsome and choleric' (this was by Alec Waugh, who called him the Purple Scot). J. B. Morton (Beachcomber) remembered him as a man of conviction, with a quick wit and enthusiasm and, surprising in a military man, 'a sense of compassion for every kind of unhappiness'. What is surprising, given his depth of knowledge of the English, and the fact that they joke about anything, is that he took it so seriously. Nevertheless, despite Macdonell's exhortations for a 'clamour for independence' towards the end of the book, he did not practice what he preached, and instead of 'leading from the front' by preaching his new gospel from Edinburgh, he remained in England for the remainder of his days. For all those who feel that Scotland has been 'hard-done-by' this is a must-buy book. New introduction by Alan Sutton

Writing under the pseudonym Neil Gordon, A. G. Macdonell wrote several crime and thriller novels. In the classic genre of '20s and '30s crime fiction, Macdonell managed to introduce a different element, unusual twists that keep the reader captivated and anxious to discover what came next. Silent Murders begins with murder of an elderly tramp on the road between King's Langley and Berkhampstead. Nobody really knows who the tramp was or what his background was. To his gentlemen-of-the-road peers he was known as 'Stuck-up Sam'. The only unusual aspect of the crime was a square of cardboard tied to the last surviving button of the tramp's ragged overcoat and on which was written the word 'Three.' The next victim could not have been different; for the gentleman silently shot through the open window of a taxi, stationery in traffic, was Mr Aloysius Skinner, Chairman of the Imperial Cochineal Company. A clue, for what it was worth, was a piece of white cardboard on which was printed in ink the single word 'Four', presumably thrown through the open window by the murderer.

Another murder took place at a quiet family tennis party in suburbia, with the host's elder brother being the unfortunate victim of the bullet. The police assumed the bullet was intended for the host, Mr Henry Maddock, a gentleman of great wealth with a dubious background in Africa from where poverty had changed with peculiar suddenness to riches. But with skill, ingenious twists, and a fast moving story-line, a tale is woven to show that not all was what it seemed...New Introduction by Alan Sutton

Another murder took place at a quiet family tennis party in suburbia, with the host's elder brother being the unfortunate victim of the bullet. The police assumed the bullet was intended for the host, Mr Henry Maddock, a gentleman of great wealth with a dubious background in Africa from where poverty had changed with peculiar suddenness to riches. But with skill, ingenious twists, and a fast moving story-line, a tale is woven to show that not all was what it seemed...New Introduction by Alan Sutton

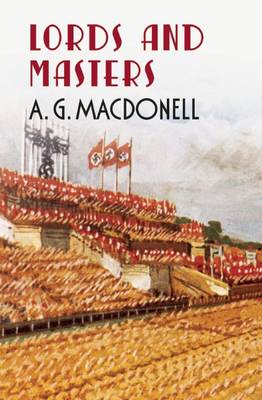

Lords and Masters is a work of fiction, but with mastery and style Macdonell uses his undoubted journalistic skill to unmask much that was unpleasant in the West End Society circles of the early 1930s. He exposes the hypocrisy of the monied class and with biting satire weaves a tale of intrigue, turning it into a thriller. His character depiction of the unscrupulous war-profiteer Sir Montagu Anderton-Mawle is a masterpiece and his ability to so ably define all that is wrong in the world - as relevant today as it was in the 1930s - reveals a genius in the art of narrative composition. Although written in 1936, Macdonell was early in seeing that war was becoming inevitable and in Lords and Masters he foresaw with frightening prescience how events would unfold. He was correct in foreseeing the attack on Singapore, but was happily wrong in regard to Japanese attacks on San Francisco and Montreal. The book is built around the character of James Hanson, a steel millionaire, and the cynical manoeuvrings of those who would seek to profiteer out of human misery. James' youngest daughter, Veronica, is a Nazi-lover, presumably modelled on Unity Mitford. "Veronica, dear," said Mrs.

Hanson admiringly, "aren't you being a little impertinent?" "No, seriously, Daddy, that atrocity stuff is all rot. Hitler wouldn't allow it for a moment. He isn't that sort of man. A few Jews have been beaten up perhaps, but that's nothing. Veronica, who heartily despised the physical appearance of any male under about six-foot-three, was not so narrow-minded as to despise male intelligence simply because it was encased in a relatively dwarfish body. After all, no one could call the Fuehrer particularly handsome, and yet what a mammoth intellect he had got! Dr. Goebbels was positively ugly, but look how he scattered the non-Aryans with his inner fires of patriotism and genius! Happily for Macdonell, England was not invaded in 1940, otherwise he might have been on the list of those to be rounded up.

Hanson admiringly, "aren't you being a little impertinent?" "No, seriously, Daddy, that atrocity stuff is all rot. Hitler wouldn't allow it for a moment. He isn't that sort of man. A few Jews have been beaten up perhaps, but that's nothing. Veronica, who heartily despised the physical appearance of any male under about six-foot-three, was not so narrow-minded as to despise male intelligence simply because it was encased in a relatively dwarfish body. After all, no one could call the Fuehrer particularly handsome, and yet what a mammoth intellect he had got! Dr. Goebbels was positively ugly, but look how he scattered the non-Aryans with his inner fires of patriotism and genius! Happily for Macdonell, England was not invaded in 1940, otherwise he might have been on the list of those to be rounded up.