NIAS Monographs

1 primary work

Book 153

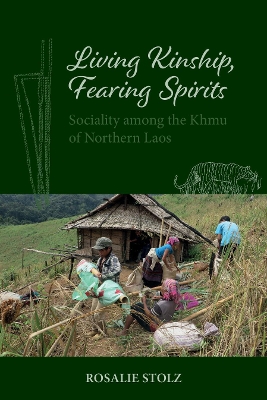

How can we conceive of kinship and sociality in the rapidly transforming uplands of mainland Southeast Asia? How to write about kinship in a way that neither falls into the trap of taking for granted kinship phenomena nor ignores the body of knowledge from earlier research? This in-depth study uses its rich findings from extensive fieldwork among the Khmu, upland dwellers of northern Laos, to bridge the divide between classical ethnography and modern approaches to kinship studies.

Here, the author offers a fresh perspective on kinship by, first of all, stepping backwards and delving into how it is actually lived locally in northern Laos. She highlights that not only the beginning of life but also its ending deserves our attention when considering the relevance of kinship. Indeed, to a considerable extent, living kinship is about death. The context of kinship and sociality among the Khmu is significant here, these being framed by ties of matrilateral cross-cousin marriage and patrilineal descent - concepts on which this study casts new light.

Dr Stolz explores this complexity in an absorbing series of intimate and self-reflective accounts. These touch upon a variety a topics, beginning with the language of kinship, then proceeding to examine the house, the changing importance of kinship throughout the life cycle, the key roles that gifting and commensality play, the meaning of work and, finally, to offer glimpses of the intricacies of village sociality and its cosmological dimensions. The underlying approach here is asking how the nature and praxis of kinship bring us closer to understanding what it means to live kinship - not just in upland northern Laos but in other societies as well. This is a significant study, one of long-term significance.

Here, the author offers a fresh perspective on kinship by, first of all, stepping backwards and delving into how it is actually lived locally in northern Laos. She highlights that not only the beginning of life but also its ending deserves our attention when considering the relevance of kinship. Indeed, to a considerable extent, living kinship is about death. The context of kinship and sociality among the Khmu is significant here, these being framed by ties of matrilateral cross-cousin marriage and patrilineal descent - concepts on which this study casts new light.

Dr Stolz explores this complexity in an absorbing series of intimate and self-reflective accounts. These touch upon a variety a topics, beginning with the language of kinship, then proceeding to examine the house, the changing importance of kinship throughout the life cycle, the key roles that gifting and commensality play, the meaning of work and, finally, to offer glimpses of the intricacies of village sociality and its cosmological dimensions. The underlying approach here is asking how the nature and praxis of kinship bring us closer to understanding what it means to live kinship - not just in upland northern Laos but in other societies as well. This is a significant study, one of long-term significance.