French List

10 total works

This is a tale of dramatic episodes, told through intermingling voices and the atmospherics of the austere Breton landscape. Ultimately, it is a story of obsessional love and of a parallel sibling bond that is equally strong.

Forty-eight brilliant and sensual color images accompany the text, as Quignard questions the origin of our being and explains the unexplainable, while noted translator Chris Turner lends a crisp voice to the entire collection.

As in the previous volumes in this series published by Seagull, Roving Shadows and The Silent Crossing, the text is a rich mix of anecdote and reflection, of aphorism and quotation, of enigmatic glimpses of the present and confident, pointed borrowings from the past - particularly the European classical past in which the author is so much at home. But when Quignard raids the murkier corners of the human record, he does so not as a historian but as an antiquarian. He is not someone interested in the world for its prim and proper historical narratives (after all, as he points out, 'In the USSR, for example, in the middle of last century, the past was completely unpredictable. For fifty years what had happened in the past changed from one day to the next.'). He is in pursuit, rather, of those stories which repeat and echo across time, stories which, if not literally timeless, dance to a rhythm that we do not ordinarily contemplate, a rhythm that channels a force which seems at times to exceed our everyday conceptions of the transcendent by many orders of magnitude.

This powerful transformation from celebration to fear is a change whose consequences, Quignard argues, we are still dealing with today, making "Sex and Terror" an intriguing reconsideration of ancient Rome that transcends its history.

By reading this fragmentary, episodic assemblage of intimate experiences and borrowed tales, we open up a space of liberty, creating for the reader space for meditation and, perhaps, liberation.

The whole, written in a musical style not far removed from that of Couperin, whose piano composition "Les Ombres" errantes lends the book its title, coheres into a work of literature that reverberates in the psyche long after one has laid it down. "The Roving Shadows" is a rare and wondrous tour de force that cements Quignard's reputation in contemporary world literature. Available now for the first time in English, this boldly adventurous work will find a new and welcoming audience.

So writes Pascal Quignard of his monumental book series, Last Kingdom. In the latest volume, The Fount of Time, he focuses on the paradoxically immediate presence in our lives of the deepest, most distant past. He explores this subject through a multitude of mediums: fragments of autobiography; curious folktales; literary snippets; historical anecdotes both classical and modern; ruminations on biology, archaeology, and linguistics. Using all of these forms, he confronts dimensions of human experience which, though customarily conveyed in legend, myth, and dreams, run somehow beneath the everyday world and yet are part of our most tangible reality.

To enter Quignard’s horizonless time-space is to embrace a rich vision in which the totality of human history and culture is placed disconcertingly on a single footing. In The Fount of Time we are able to glimpse—whether through obscure cultural detail or unusual anecdote—“another world beneath the world.”

In Pascal Quignard’s writing, philology hunts for wild game in a dark forest. The Unsaddled, which features horses as its central figure, is no exception. Taking off from puns, multifarious imagery, and metaphorical meanings—“to be baffled,” “to be thrown”—that the book’s title provides, Quignard focuses on life-changing moments. We meet George Sand (whose father died after being thrown from his horse), Saint Paul, Abelard, Agrippa d’Aubigné, and countless other writers, philosophers, theologians, or kings who fell off their horses—not to forget Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was knocked over by a dog. Being “unsaddled” can also be associated, as Quignard shows in regard to Nietzsche, with an “overturning” of values. Scenes of war, hunting, “fleeing” or sexuality—“When lovers have a horse ride, they gallop in another world”—come before our eyes, each time from those unsettling vantage points that Quignard knows how to find. As ever, he ranges far and wide in his intense quest, taking examples from across human history, from the neolithic age to his own childhood memories of postwar Le Havre in northern France.

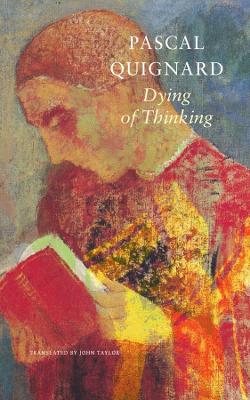

Dying of Thinking is the ninth volume of Pascal Quignard’s Last Kingdom series. It explores three themes: how thought and death coincide, how thought is close to melancholy, and how thought takes shelter near traumatism. One who thinks, Quignard shows us, “compensates” for a very ancient abandonment. Even as a dream is a meaning whose disorderly, condensed, paradoxical images intuit something which has preceded sleep and which returns in them, thought is a meaning which uses words that are written, re-transcribed, dissected, etymologized and neologized. Throughout the Last Kingdom series, Quignard has sought to experience another way of thinking, one that has nothing to do with philosophy, a way of attaching himself “literally” to texts and of progressing by decomposing the imagery of dreams. Dying of Thinking is the heart of this quest.