McGill-Queen's/Beaverbrook Canadian Foundation Studies in Art History

4 total works

Jean Paul Riopelle est surtout connu pour les célèbres toiles abstraites de sa maturité artistique. Toutefois, François Marc Gagnon amorce cette histoire fascinante avec les premières peintures et l'adhésion précoce à l'objectivité, avant de sonder la participation de l'artiste à l'automatisme et l'incidence durable de ce mouvement sur son œuvre. Gagnon retrace les premières étapes du cheminement de Riopelle depuis le style figuratif traditionnel enseigné par Henri Bisson, son premier professeur, jusqu'au virage subjectif inspiré par une exposition itinérante d'art hollandais et, en particulier, des toiles de Vincent Van Gogh, ainsi qu'aux expériences automatistes dans un atelier d'une ruelle de Montréal où le peintre travaille en compagnie de Marcel Barbeau et de Jean Paul Mousseau. Dès 1946, Riopelle est un émissaire de l'automatisme à Paris, où il organise la première exposition collective consacrée à ce style. L'auteur montre que malgré la perception d'un désintéressement idéologique, Riopelle a joué un rôle déterminant dans la publication du Refus global, manifeste dont il a dessiné la couverture et qu'il défendra publiquement, alors que la controverse agite les cercles artistiques et intellectuels du Québec. En 1949, après avoir embrassé la notion automatiste d'une peinture sans préconception, Riopelle adopte un style très personnel, où le hasard tient une place prépondérante. L'auteur retrouve cette démarche dans l'œuvre et les témoignages du peintre lui-même, qu'il fait dialoguer habilement avec les textes de philosophes et de théoriciens sur le rôle du hasard dans la créativité. Il propose en outre une analyse formelle du style et de la technique privilégiés par son sujet au moment où il abandonne définitivement le pinceau pour la spatule. Dans ce premier examen approfondi du rapport de Riopelle à la peinture américaine et à Jackson Pollock en particulier, il remet en question l'idée, pourtant largement acceptée, d'une influence de Pollock, qu'il juge peu probante. Cet ouvrage d'érudition, stimulant et clair, dernier de la longue carrière de l'auteur, est porté comme toujours par une écriture brillante. Il se distingue par son originalité, son intégrité et une connaissance approfondie de l'œuvre et du milieu de l'artiste, ce « trappeur supérieur » selon le mot d'André Breton.

From his beginnings as a rural church decorator, to his role as catalyst of the social and artistic manifesto the Refus global, to a career as Canada's pre-eminent practitioner of radical abstraction abroad, Paul-Emile Borduas's short life encompassed the reversals and contradictions of the modern condition. Drawing on a lifetime of published research, Francois-Marc Gagnon's comprehensive biography is a far-reaching exploration of a Quebec cultural figure renowned for both his art and his thought. Gagnon details each period of Borduas's dynamic career - his apprenticeship with Ozias Leduc, his teaching in Montreal and the role within the Automatiste group, his move to New York at the height of the Abstract Expressionist movement, and then, against the current of the times, to Paris, where he created the iconic images of his "cosmic" period. Borduas's relentless search for an authentic art often put him at odds with his surroundings.

As an avant-garde artist in a Montreal art world bound by tradition, his most important work had to be exhibited in makeshift venues; as a surrealist-influenced francophone in New York, he recognized the importance of the major figures of Abstract Expressionism but maintained an independent style and method. A full appreciation of Borduas's radical stance - an artistic and intellectual orientation that was always towards the universal - transforms a Canadian cultural landscape where the narrative of artistic modernism centres on figurative landscape art. An original and rigorously researched work, Paul-Emile Borduas: A Critical Biography provides an English-language readership with a much-needed understanding of a seminal modernist, an exemplary figure in Canadian art, and the origins of modern art in North America.

As an avant-garde artist in a Montreal art world bound by tradition, his most important work had to be exhibited in makeshift venues; as a surrealist-influenced francophone in New York, he recognized the importance of the major figures of Abstract Expressionism but maintained an independent style and method. A full appreciation of Borduas's radical stance - an artistic and intellectual orientation that was always towards the universal - transforms a Canadian cultural landscape where the narrative of artistic modernism centres on figurative landscape art. An original and rigorously researched work, Paul-Emile Borduas: A Critical Biography provides an English-language readership with a much-needed understanding of a seminal modernist, an exemplary figure in Canadian art, and the origins of modern art in North America.

The Codex Canadensis and the Writings of Louis Nicolas

by Louis Nicolas and Francois-Marc Gagnon

Published 29 September 2011

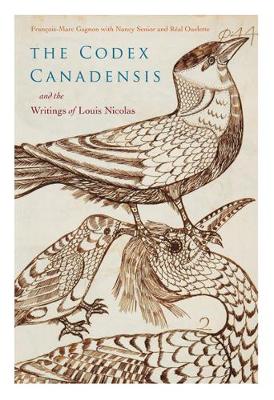

Part art, part science, part anthropology, this ambitious project presents an early Canadian perspective on natural history that is as much artistic and fantastical as it is encyclopedic. Edited and introduced by Francois-Marc Gagnon, The Codex Canadensis and the Writings of Louis Nicolas showcases an intriguing attempt to document the life of the new world - flora, fauna, and aboriginal. The book brings together for the first time the illustrated Codex Canadensis and The Natural History of the New World, following Gagnon's argument that both can be attributed to Louis Nicolas, a French Jesuit priest who travelled throughout Canada between 1664 and 1675. Histoire Naturelle des Indes Occidentales, originally written in classical French, has been put in modern French by Real Ouellet and translated into English by Nancy Senior. The Natural History presents a pre-Linnaean botany and pre-Darwinian account of living things, including hundreds of species of plants and vivid descriptions of wildlife. It is thoroughly annotated, focusing on the contemporary identification of species, as the result of a pan-Canadian collaboration of experts in fields from linguistics to biology and botany.

The Codex Canadensis, currently in the collection of the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, is reproduced in full and provides both a fascinating visual account of wildlife as Nicolas saw it and a rare example of early Canadian art. Gagnon's introduction profiles Louis Nicolas and analyses connections between his work and European examples of natural illustration from the period. The Codex Canadensis and the Writings of Louis Nicolas shows how the wildlife and native inhabitants of the new world were understood and documented by a seventeenth-century European and makes available fundamental documents in the history and visual culture of early North America.

The Codex Canadensis, currently in the collection of the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, is reproduced in full and provides both a fascinating visual account of wildlife as Nicolas saw it and a rare example of early Canadian art. Gagnon's introduction profiles Louis Nicolas and analyses connections between his work and European examples of natural illustration from the period. The Codex Canadensis and the Writings of Louis Nicolas shows how the wildlife and native inhabitants of the new world were understood and documented by a seventeenth-century European and makes available fundamental documents in the history and visual culture of early North America.

The artist Jean Paul Riopelle is best known for his renowned mature abstract style. In this fascinating history, François-Marc Gagnon begins with the artist's first paintings and his early commitment to objectivity to explore Riopelle's involvement with the Automatiste movement and its lasting impact on his work. Gagnon traces Riopelle's early development from the traditional figurative style imparted by his first teacher, Henri Bisson, through a turn toward the subjective on seeing a travelling exhibition of Dutch art that included the works of Vincent van Gogh, to Automatiste experiments in an alley studio in Montreal where he painted with Marcel Barbeau and Jean-Paul Mousseau. As early as 1946, Riopelle was an Automatiste emissary in Paris, organizing the first group show there. In spite of the perception that Riopelle was ideologically disinterested, Gagnon shows that he was in fact instrumental to the publication of Refus global – which includes his art on its cover – and publicly defended the manifesto amid controversy in both artistic and intellectual circles in Quebec. Initially devoted to the Automatiste notion of painting without preconception, by 1949 Riopelle was breaking into a markedly individual style in which the idea of chance was central. Gagnon reads this approach through Riopelle's own work and testimony, placing it in careful conversation with writing by philosophers and theorists on the role of chance in creativity. Gagnon also makes use of formal analysis of Riopelle's style and technique as he abandoned the paintbrush to work exclusively with the spatula. The well-established narrative of Jackson Pollock's influence on Riopelle is tested – and found wanting – in the first extended examination of Riopelle's relationship to American painting and to Pollock in particular. Demonstrating the qualities of scholarship and writing that were the hallmark of Gagnon's long career, his last book is engaging and clear and stands out for its originality, integrity, and profound insight into the work and milieu of the artist that André Breton called "the peerless trapper."