WWII Historic Battlefields

6 total works

The Normandy Battlefields: D-Day & the Bridgehead ended as the Allies fought to expand their D-Day foothold. In Bocage and Breakout, Leo Marriott and Simon Forty take the story forward as the success of the invasion continued into the Cotentin, with Cherbourg falling on 29 June, before it bogged down in face of determined German defense and the bocage countryside—innumerable small fields surrounded by hedgerows, each one hiding anti-tank weapons, mortars and machine guns. As US First Army fought its way south, on the eastern edges of the bridgehead, British and Canadian forces were fighting a war of attrition around Caen facing the bulk of the German armor as division after division was fed into Normandy. Like a pressure cooker, the fighting intensified until, seven weeks after D-Day, Operation ‘Cobra’ broke the German line. Quickly Patton’s Third Army, operational from 1 August, flooded through the gap exploiting the German confusion, encircling what was left of the German armies in the Falaise Pocket and advancing quickly through into Brittany. Three weeks later, the Battle of Normandy was over, the routed German Army—without most of its heavy weapons left in the Falaise Pocket or on the banks of the Seine—was retreating helter skelter back towards Germany and the Low Countries pursued by the Allies in a reverse of the 1940 Blitzkrieg campaign.

The three months of war in June–July 1944 were brutal, with losses of front-line troops as heavy as in World War I. The German defense was tenacious, particularly in face of Allied air supremacy. The Allies struggled to get into a position to allow their more mobile forces room for maneuver and and the fighting was ferocious.

When victory came, it came at a cost: 209,672 casualties among the ground forces, including 36,976 killed and 19,221 missing. The Allied air forces lost 16,714 airmen. The corresponding German losses were even more significant: some 450,000 men, of whom 240,000 were killed or wounded. More important to the Germans were the losses of heavy equipment—tanks, assault guns, artillery, personnel carriers. As an example, 12th SS Panzer Division had lost 94% of its armor, nearly all of its artillery and 70% of its vehicles. With c20,000 men and 150 tanks before the campaign, after Falaise it had 300 men and 10 tanks.

Mixing text, maps and images, many of them specially commissioned including aerial photography, The Normandy Battlefields: Bocage and Breakout explains and interprets the complexities of the Normandy campaign in an original and cohesive package.

The three months of war in June–July 1944 were brutal, with losses of front-line troops as heavy as in World War I. The German defense was tenacious, particularly in face of Allied air supremacy. The Allies struggled to get into a position to allow their more mobile forces room for maneuver and and the fighting was ferocious.

When victory came, it came at a cost: 209,672 casualties among the ground forces, including 36,976 killed and 19,221 missing. The Allied air forces lost 16,714 airmen. The corresponding German losses were even more significant: some 450,000 men, of whom 240,000 were killed or wounded. More important to the Germans were the losses of heavy equipment—tanks, assault guns, artillery, personnel carriers. As an example, 12th SS Panzer Division had lost 94% of its armor, nearly all of its artillery and 70% of its vehicles. With c20,000 men and 150 tanks before the campaign, after Falaise it had 300 men and 10 tanks.

Mixing text, maps and images, many of them specially commissioned including aerial photography, The Normandy Battlefields: Bocage and Breakout explains and interprets the complexities of the Normandy campaign in an original and cohesive package.

The speed of the German Blitzkrieg in 1940 and the relative ease with which they brushed aside Allied defenses meant four years of occupation. But in June 1944—this time with American forces—the Allies finally returned for a rematch. The destruction of German forces in Normandy’s Falaise pocket, on August 14,was as quick as the Blitzkrieg had been: by September British troops were in Ghent and Liege; Canadian forces liberated Ostend, and in northeast France Patton's Third Army was moving rapidly to the German border, taking Rheims on August 29 and Verdun on the 30th. Paris was liberated on August 25th.

The liberation of the Low Countries would not prove as straightforward, however. Operation Market Garden—Montgomery's brave thrust toward the Rhine at Arnhem—started on September 17 and hoped to end German resistance at a stroke. But it ended in failure on the 25th with over 6,000 paratroopers captured.

V-1 flying bombs had meantime been launched from northern France and the Low Countries from August 1944. During September the more frightening German V-2s began raining in. In late October, belated operations began to clear the Scheldt Estuary and open the port of Antwerp to the Allies, and took nearly a month. Belgium was almost free of the Nazi yoke and the Netherlands looked likely to be cleared before Christmas.

Then, on December 16, came Hitler's last roll of the dice: a major German counter-offensive in the Ardennes aiming to split the Allied armies and retake Antwerp. It turned out to be their last try: the American defenders held, and finally with better weather, Patton's army and Allied air superiority told. With the Germans having shot their last bolt, in the spring the Rhine was gained.

Race to the Rhine, a companion volume to The Normandy Battlefields, links modern aerial photography with contemporary illustrations to provide a modern interpretation of the battles, replete with maps, diagrams and photos. It is now 70 years since Western Europe was freed from its occupation, and this book provides a graphic view of how it was accomplished. For those interested in visiting the sites, it supplies a guide to the places that best represent the battles today.

The liberation of the Low Countries would not prove as straightforward, however. Operation Market Garden—Montgomery's brave thrust toward the Rhine at Arnhem—started on September 17 and hoped to end German resistance at a stroke. But it ended in failure on the 25th with over 6,000 paratroopers captured.

V-1 flying bombs had meantime been launched from northern France and the Low Countries from August 1944. During September the more frightening German V-2s began raining in. In late October, belated operations began to clear the Scheldt Estuary and open the port of Antwerp to the Allies, and took nearly a month. Belgium was almost free of the Nazi yoke and the Netherlands looked likely to be cleared before Christmas.

Then, on December 16, came Hitler's last roll of the dice: a major German counter-offensive in the Ardennes aiming to split the Allied armies and retake Antwerp. It turned out to be their last try: the American defenders held, and finally with better weather, Patton's army and Allied air superiority told. With the Germans having shot their last bolt, in the spring the Rhine was gained.

Race to the Rhine, a companion volume to The Normandy Battlefields, links modern aerial photography with contemporary illustrations to provide a modern interpretation of the battles, replete with maps, diagrams and photos. It is now 70 years since Western Europe was freed from its occupation, and this book provides a graphic view of how it was accomplished. For those interested in visiting the sites, it supplies a guide to the places that best represent the battles today.

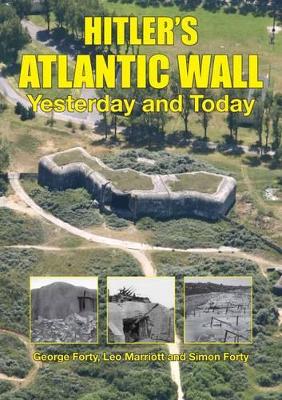

Masters of the continent, the Nazis realized that they would have to defend their gains, and once the United States entered the war, redoubled their efforts. Using forced and slave labor they built a chain of defensive positions, coastal batteries, and beach defenses from the top of Norway to the Franco-Spanish border. However, as was so typical of the Nazis, while the bunkers and batteries seem impressively constructed, and the Atlantic Wall has left a permanent reminder of the years of Nazi domination, it was crippled by lack of strategic planning, internal bickering, and a multitude of command structures that did not communicate with each other effectively. In June 1944 the Allies burst through the wall, and while it took many lives to break the crust of the German defenses, the vaunted Atlantic Wall proved ineffective save for the fortresses the Allies bypassed and subdued later. Using the same formula as in their books on The Normandy Battlefields and Race to the Rhine, Leo Marriott and Simon Forty combine bespoke aerial photography with old photographs, maps, and current illustrations to provide a pictorial analysis of the subject—Around 500 illustrations ensure the subject is well covered. After opening sections on the construction of the wall, the defensive plan, and the different structures that were built, Hitler’s Atlantic Wall yesterday and today provides a survey of the key locations and what can be seen today—including many of the museums that interpret them. The bulk of the book is divided geographically by country, dealing with France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway. After 70 years, the Atlantic Wall is still a remarkable reminder of the war years, and one that continues to fascinate.

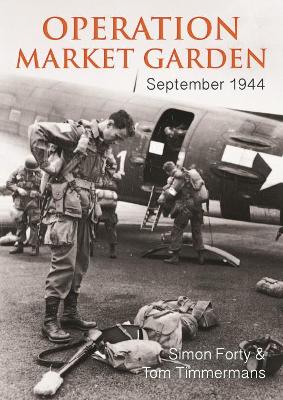

The battle of Normandy ended as the Allied armies crossed the Seine at the end of August 1944, a month after Operation Cobra had broken the stalemate. The Allies harried the retreating Germans, who left their tanks and heavy weapons south of the Seine, and by mid-September the Allies were coming up against the defences of Germany itself, the impressive Westwall.

As far as the Allies were concerned, the Germans were beaten. The scent of immediate victory was in the air, the only question was where to apply the coup de grace. Logistics demanded that this should be a single thrust rather than Eisenhower’s broad front approach. Montgomery—the architect of victory in Normandy—proposed a daring plan to circumvent the Westwall, thrust towards Berlin, and make use of the newly created 1st Allied Airborne Army. The plan was simple: use the Paratroopers to hold key bridges along a single route along which British XXX Corps would make an advance that would be “rapid and violent, and without regard to what is happening on the flanks.” US 101st Airborne would land north of Eindhoven; 82nd Airborne at Nijmegen; British 1st Airborne at Arnhem—the so-called “bridge too far.”

Unfortunately, the plan was flawed, the execution imperfect, and the Germans far from beaten. In spite of the audacious actions of the Paratroopers who would cover themselves with glory, Operation Market Garden showed that the German ground forces would still provide the Allies with stiff opposition in the West.

And then, in 1977, A Bridge Too Far came out. With levels of realism that wouldn’t be approached for twenty years, the movie produced a view of the battle that subverted reality and permeated public perception. Just as George C. Scott produced the definitive Patton, so A Bridge Too Far provided an unnuanced view of the battles that historians have battled to correct ever since.

As with its companion volumes on D-Day, the Bocage, and the Ardennes battlefields, this book provides a balanced, up-to-date view of the operation making full use of modern research. With over 500 illustrations including many maps, aerial and then and now photography, it will provide the reader with an easy-to-read, up-to-date examination of each part of the operation, benefitting from on-the-ground research by Tom Timmermans, who lives in Eindhoven.

As far as the Allies were concerned, the Germans were beaten. The scent of immediate victory was in the air, the only question was where to apply the coup de grace. Logistics demanded that this should be a single thrust rather than Eisenhower’s broad front approach. Montgomery—the architect of victory in Normandy—proposed a daring plan to circumvent the Westwall, thrust towards Berlin, and make use of the newly created 1st Allied Airborne Army. The plan was simple: use the Paratroopers to hold key bridges along a single route along which British XXX Corps would make an advance that would be “rapid and violent, and without regard to what is happening on the flanks.” US 101st Airborne would land north of Eindhoven; 82nd Airborne at Nijmegen; British 1st Airborne at Arnhem—the so-called “bridge too far.”

Unfortunately, the plan was flawed, the execution imperfect, and the Germans far from beaten. In spite of the audacious actions of the Paratroopers who would cover themselves with glory, Operation Market Garden showed that the German ground forces would still provide the Allies with stiff opposition in the West.

And then, in 1977, A Bridge Too Far came out. With levels of realism that wouldn’t be approached for twenty years, the movie produced a view of the battle that subverted reality and permeated public perception. Just as George C. Scott produced the definitive Patton, so A Bridge Too Far provided an unnuanced view of the battles that historians have battled to correct ever since.

As with its companion volumes on D-Day, the Bocage, and the Ardennes battlefields, this book provides a balanced, up-to-date view of the operation making full use of modern research. With over 500 illustrations including many maps, aerial and then and now photography, it will provide the reader with an easy-to-read, up-to-date examination of each part of the operation, benefitting from on-the-ground research by Tom Timmermans, who lives in Eindhoven.

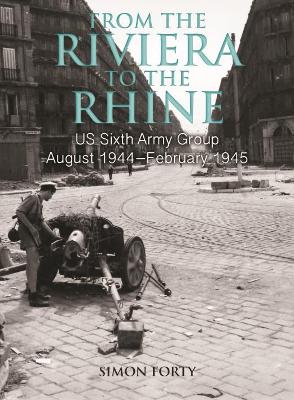

Two months after D-Day, just as the battle of Normandy was reaching its climax, with all eyes on the Falaise Pocket, the Allies unleashed the second invasion of France not in the Pas de Calais but the French Riviera. Immaculately planned, effectively undertaken, the Allies quickly broke out of their bridgehead, drove 400 miles into France in three weeks, and liberated 10,000 square miles of French territory while inflicting 143,250 German casualties. On September 10 they linked up with Patton’s Third Army and advanced into the Vosges Mountains, taking Strasbourg and holding the area against the Germans’ final big attack in the west: Operation Nordwind in January 1945.

US Seventh Army and 6th Army Group undertook a successful campaign placing a third Allied army group with its own independent supply lines, in northeastern France at a time when the two northern Allied army groups were stretched to the limit. Without this force the Allies would have struggled to hold the frontage to Switzerland and Third Army would have been exposed to attack in its southern flank—something that could have had disastrous repercussions particularly during the Ardennes offensive of December 1944.The images of palm trees and azure seas obscure our view of this campaign. It was no cakewalk. The Germans knew the Allies were coming and had strong defences in the area. A shortage of landing craft, vehicles, and matériel meant that the US Seventh and French First armies were restricted in the assault. The heavy fog and anti-glider defences made for a difficult airborne assault, but it was carried out effectively, the amphibious assault was textbook in execution and the invasion of southern France ended up as a significant victory.

But the story of 6th Army Group wasn’t finished. Taking up a position on the east flank of Third Army it fought its way through the Vosges and withstood the Germans’ last throw: Operation Nordwind—the vain attempt to relieve pressure on the Ardennes assault by attacking in the Vosges. Heavy fighting pressed hard towards Strasbourg but the Allies were ultimately victorious, inflicting severe losses on the Germans.

US Seventh Army and 6th Army Group undertook a successful campaign placing a third Allied army group with its own independent supply lines, in northeastern France at a time when the two northern Allied army groups were stretched to the limit. Without this force the Allies would have struggled to hold the frontage to Switzerland and Third Army would have been exposed to attack in its southern flank—something that could have had disastrous repercussions particularly during the Ardennes offensive of December 1944.The images of palm trees and azure seas obscure our view of this campaign. It was no cakewalk. The Germans knew the Allies were coming and had strong defences in the area. A shortage of landing craft, vehicles, and matériel meant that the US Seventh and French First armies were restricted in the assault. The heavy fog and anti-glider defences made for a difficult airborne assault, but it was carried out effectively, the amphibious assault was textbook in execution and the invasion of southern France ended up as a significant victory.

But the story of 6th Army Group wasn’t finished. Taking up a position on the east flank of Third Army it fought its way through the Vosges and withstood the Germans’ last throw: Operation Nordwind—the vain attempt to relieve pressure on the Ardennes assault by attacking in the Vosges. Heavy fighting pressed hard towards Strasbourg but the Allies were ultimately victorious, inflicting severe losses on the Germans.

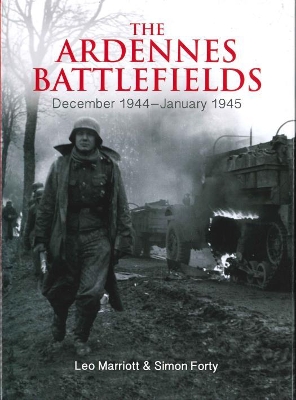

Just after its seventieth anniversary, the Battle of the Bulge has lost none of its impact. The largest battle fought by US troops on the continent of Europe started in a surprise attack on December 16, 1944, by four German armies, spearheaded by the cream of the German Panzer forces. Under the cover of bad weather and heavy snow, Hitler’s last roll of the dice was intended to retake Antwerp, split the Allies, divide their political leadership, and force peace in the West, thus allowing the German forces to concentrate on defeating the Red Army. Strategic pipedream or not, the attack was furious and drained the Eastern Front of reinforcements: 12 armored and 29 infantry divisions, some 2,000 tanks and assault guns—mainly PzKpfw IVs (800), Panthers (750) and Tigers (250 including some of the new King Tigers)— spearheaded the assault, which smashed into the American First and Ninth Armies.

Near-complete surprise was achieved thanks to a combination of Allied overconfidence, preoccupation with offensive plans, and poor reconnaissance. The Germans attacked where least expected—the forested Ardennes—a weakly defended section of the Allied line, taking advantage of the weather conditions, which grounded the Allies’ overwhelmingly superior air forces. The Allied response was magnificent. Initial reverses brought out the best of Eisenhower’s armies, which fought with determination and grit against the enemy and the elements. The harsh battles are best summed up by the defense of the northern shoulder around the Elsenborn Ridge, the battle for St. Vith, and in the south the siege of Bastogne, where the town’s commander, Gen. McAuliffe, rejected German calls for surrender with the pithy reply: “Nuts.”

Within ten days the German attack had been nullified. Patton, at the time planning an attack further south, wheeled his Third Army round in a brilliant maneuver that relieved Bastogne and set up a counterattack which would drive the Germans back behind the Rhine. The Ardennes Battlefields includes details of what can be seen on the ground today—hardware, memorials, museums, and cemeteries—using a mixture of media to provide an overview of the campaign: maps old and new highlight what has survived and what hasn’t; then and now photography allows fascinating comparisons with the images taken at the time; aerial photos give another angle to the story. The fifth book by Leo Marriott and Simon Forty provides a different perspective to this crucial battlefield.

Near-complete surprise was achieved thanks to a combination of Allied overconfidence, preoccupation with offensive plans, and poor reconnaissance. The Germans attacked where least expected—the forested Ardennes—a weakly defended section of the Allied line, taking advantage of the weather conditions, which grounded the Allies’ overwhelmingly superior air forces. The Allied response was magnificent. Initial reverses brought out the best of Eisenhower’s armies, which fought with determination and grit against the enemy and the elements. The harsh battles are best summed up by the defense of the northern shoulder around the Elsenborn Ridge, the battle for St. Vith, and in the south the siege of Bastogne, where the town’s commander, Gen. McAuliffe, rejected German calls for surrender with the pithy reply: “Nuts.”

Within ten days the German attack had been nullified. Patton, at the time planning an attack further south, wheeled his Third Army round in a brilliant maneuver that relieved Bastogne and set up a counterattack which would drive the Germans back behind the Rhine. The Ardennes Battlefields includes details of what can be seen on the ground today—hardware, memorials, museums, and cemeteries—using a mixture of media to provide an overview of the campaign: maps old and new highlight what has survived and what hasn’t; then and now photography allows fascinating comparisons with the images taken at the time; aerial photos give another angle to the story. The fifth book by Leo Marriott and Simon Forty provides a different perspective to this crucial battlefield.