The History of Psychoanalysis

2 total works

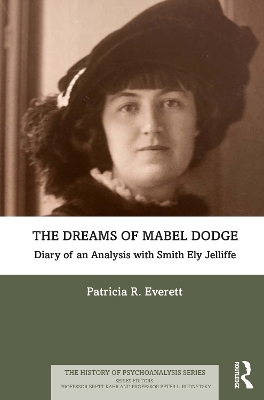

In 1916, salon host Mabel Dodge entered psychoanalysis with Smith Ely Jelliffe in New York, recording 142 dreams during her six-month treatment. Her dreams, as well as Jelliffe’s handwritten notes from her analytic sessions, provide an unusual and virtually unprecedented access to one woman’s dream life and to the private process of psychoanalysis and its exploration of the unconscious.

Through Dodge’s dreams—considered together with Jelliffe’s notes, annotations drawn from her memoirs and unpublished writings, and correspondence between Dodge and Jelliffe during the course of her treatment—the reader becomes immersed in the workings of Dodge’s heart and mind, as well as the larger cultural embrace of psychoanalysis and its world-shattering views. Jelliffe’s notes provide a rare glimpse into the process of dream analysis in an early psychoanalytic treatment, illuminating how he and Dodge often embarked upon an examination of each element of the dream as they explored associations to such details as color and personalities from her childhood.

The dreams, with their extensive annotations, provide compelling and original material that deepens knowledge about the early practice of psychoanalysis in the United States, this period in cultural history, and Dodge’s own intricately examined life. This book will be of great interest to psychoanalysts in clinical practice, as well as scholars of the history of psychoanalysis and students of dreams.