Metaphorosis Reviews

Summary

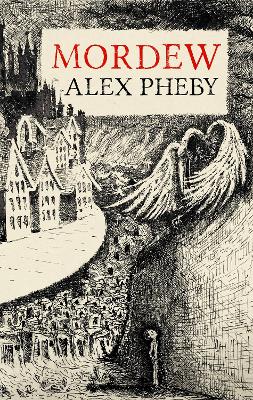

Nathan lives in the slums of Mordew, the Master's city, and feeds himself, his prostitute mother, and dying father scavenging from the Living Mud that surrounds him. But he has a Spark that catches the Master's eye, and there's quite a lot more about Nathan and his origin than meets the eye.

Review

Mordew is a fascinating book with intriguing characters in a complex world. It’s unfortunately also a book that’s severely unbalanced. I’ll start by noting that my e-book (or the conversion of it to EPUB) gave its length as 814 pages. In fact, it’s just over 400, plus almost 300 glossary entries, plus a few dozen pages of (fairly vague) in-world philosophy or mysticism. I found the latter (and the initial dramatis personae) somewhat clumsy.

The book is divided into four or five parts, and the first is rock solid and captivating – the introduction to our protagonist and his world. After that, though, the book loses its way a bit. Nathan, who has grown up through hard times and choices, instantly reverts to a biddable child. There are some throwaway comments late in the book that try to paper this over, but it’s an awkward stumbling block that takes us well out of the immersive book we’ve enjoyed until then. Then there’s an interlude, and two more parts that, to my mind, are extremely rushed and hectic. While I see now that there’s a sequel novel, I think Mordew itself could, and probably should, have been broken into at least two books to give the action time to breathe, and Nathan time to develop. As is, the reader just has to take the plot on faith. This is exacerbated by the fact that, through most of the book, Nathan is much more acted upon than actor. When he does act, his choices often feel fairly random.

“The future of fantasy starts here,” says the front-cover blurb. I think it’s more accurate, though, to see Mordew as a throwback to the gothic novels of old, and particularly to Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast. But despite the similarities to Gormenghast, I think Mordew stands as its own book, and it’s disappointing to see its cover lean so heavily on Peake’s own artistic style. I do admit that, the further I got in the book, the more I thought Pheby owed to Peake, and the more I thought this was deliberate.

There’s a lot here to like, and I do expect to pick up the next book in time. However, if the first quarter of the book deserves five stars, the remainder is less convincing. There are also a fair number of punctuation and grammatical/typographical errors – a surprise in a book that’s been through two publishers and several editions. Some might be considered stylistic choices, but some are clearly just wrong.