Veronica 🦦

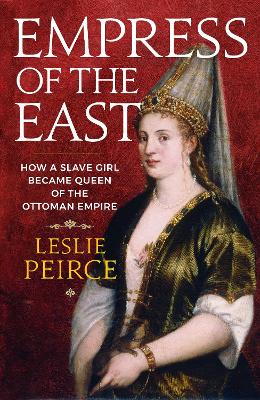

Despite its interesting subject matter, Peirce’s [b:Empress of the East: How a European Slave Girl Became Queen of the Ottoman Empire|33773618|Empress of the East How a European Slave Girl Became Queen of the Ottoman Empire|Leslie Peirce|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1484074638s/33773618.jpg|54651456] is a terribly written & biased piece that lacks structure, neglecting to include important information at logical junctures. More alarmingly, she distorts & exaggerates historical fact to embellish her subject’s power & influence, caters to fans of the ruthless second wave feminism trope, & ultimately tries to spin history into a fairytale rags-to-riches story. In the attempt to exonerate Hürrem & frame her as a heroine worth rooting for, Peirce presents her as far too brilliant, far too powerful, & far too perfect. Peirce’s Hürrem can do no wrong; she is intelligent, politically aware, & a keen manipulator of circumstance, but at the same time indisputably innocent of charges leveled against her - not even to ensure one of her sons would take the throne. Conversely, those who stood against Hürrem’s success like Mahidevran, Ibrahim, & Mustafa are consistently painted in a far more negative light. Their importance is watered down, their merits are downplayed, & their figures presented dismissively order to serve the narrative & make Hürrem look better.

When compared to her academic work, Empress falls flat on itself. While the prose is easy to read, Peirce’s writing falters as she attempts to write for a general audience. Rather than providing a scholarly analysis backed up by historical evidence, she favors a biased narrative that relies heavily on speculative “imagining”, value judgments, & tenuous yet sweeping claims. Her use of romantic & idyllic language drags down her writing rather than lift it up, & uncritically attempts to frame Hürrem & Süleyman’s relationship as a love story. The concluding statement of the introduction provides no better example of Peirce’s modus operandi, in which she asserts the Ottoman Sultanate’s survival was largely “bolstered by the reforms she introduced”, a process “generated along with the Ottoman empire’s greatest love story.”

This language is typical in the book. Peirce forces the reader to see the Ottoman world through her lens & adopt her wishful imagings, instead of allowing them to form their own views & imagine independently. Her “speculation” includes comparisons that make little sense, all the while implying that Hürrem “must have thought” of such things herself! Peirce notes that women forced into sexual servitude may not have viewed their status positively, yet at one point abhorrently tries to justify it because of the “compensations” - that these women “must” have known they probably wouldn’t have had easy lives or happy marriages in their homelands, & would be comforted that, even as palace slaves, they could at least live in the lap of luxury: “An emotionally & sexually fulfilling marriage had not necessarily been in store for them in their hometowns & villages. The common practice of arranged marriage could saddle them with husbands who were unattractive, considerably older, or even brutal. Mostly peasants, they were more likely than not destined for a life of daily toil - perhaps poverty - early death. The dynastic family to which they now belonged at least kept them in luxurious comfort - good health.”

Of course, no one knows what Hürrem thought during certain events; suggestions that she would have connected herself to other women in history, or compare the converted Ayasofya to her own experience, do not belong in a biography. Peirce can speculate - draw conclusions based on the facts that she has. However, she can’t lead readers to imagine that Hürrem ever thought of what architectural endeavors she might take on should she succeed with Süleyman, sympathized with Anne Boleyn, or compared herself to Gürcü Hatun (a Christian-born consort beloved by a Muslim ruler) - Byzantine royals like Eirene; that Süleyman instructed her in the art of war, tutored her as a diplomat, or gave her a say in how the design of the new palace harem, especially whilst Süleyman’s mother Hafsa was alive. There’s no evidence for any of these things. Such fanciful scenarios are better suited for a work of historical fiction - & considering how Peirce omits pertinent information she herself described in The Imperial Harem to suit the narrative, she might as well have written a novel!

Empress gives the impression that it was by marrying Süleyman that Hürrem became a “queen” & obtained the stature that she had. However, this is not the case. Although Peirce mentions that noblewomen married Ottoman sultans in prior centuries, she neglects to inform the reader that because royal wives were barred from having children, they were not as powerful as their slave counterparts who did. “Women without sons were women without households & therefore women of no status,” she summarized in Harem. Because the Ottomans granted greater prestige to women who bore a son over a childless one, limiting reproduction limited access to political power: “Royal wives were deprived of this most public mark of status [the patronage of public buildings], presumably because they lacked the qualification that appears to have entitled royal concubines to this privilege: motherhood. The suppression of the capacity of royal wives to bear children is an example of the Ottoman policy of manipulating sexuality & reproduction as a means of controlling power. To deny these women access to motherhood, the source of female power within the dynastic family, was to diminish the status of the royal houses from which they came.”

Peirce gives the example of Sittişah (Sitti) Hatun, who married Mehmed the Conqueror. She describes Sitti’s wedding to Mehmed, an event surrounded by great pomp & circumstance. However, she neglects to inform the reader that Sitti’s marriage to Mehmed bore no children. Franz Babinger writes that although she had wed to the great conqueror himself, the childless Sitti was ultimately powerless & died lonely & forsaken. As Peirce explained in 1993, unions such as that of Sitti & Mehmed were largely symbolic & strictly political in nature: “Although their careers as consorts of the sultans often began with the ceremonial of elaborate weddings, royal brides were ciphers in these events. What counted was the ceremony itself & what it symbolized: less the union of male & female than a statement of the relationship between two states. The function of the bride, particularly in view of the non role that awaited her as the sultan’s wife, was to symbolize the subordinate status of the weaker state.”

There is no question that Hürrem & Süleyman’s marriage rattled Ottoman society. Nevertheless, it is alarming that Peirce, who once authored a seminal work on the structure & politics of the harem, omits the fact that it was motherhood & not marriage that empowered a woman in the dynastic family. Such gaps in knowledge might lead those previously unfamiliar with the Ottoman harem to believe that marriage made Hürrem a “queen” & gave her political power, going so far to describe her & Süleyman as a “reigning couple” at one point. (Bizarrely, she does discuss abortion in Empress, yet avoids writing about dynastic family politics beyond mentioning “political planning”.)

Far more perturbing is Peirce’s insistence that Hürrem did more than she actually did for the empire. She claims that it was Hürrem who played a pivotal role in “moving the Ottoman Empire into modern times” & allowed the sultanate to survive through reforms she introduced. While she certainly paved the way in some regards for the women who followed her, Peirce overestimates Hürrem’s impact on the history of the Ottoman empire. There are other influential figures who helped preserve the sultanate, other forces that allowed it to flourish. Furthermore, Peirce downplays external factors that allowed for Hürrem’s ascent in the first place - namely the absence of a valide after 1534, not to mention Süleyman’s lasting infatuation for her - in favor of emphasizing her purportedly “unique” qualities of endurance, intelligence, & being a survivor.

Peirce goes on to anachronistically frame Hürrem as a feminist figure. In one passage, she describes her as a “forward-thinking equal opportunity employer” who “challenged women’s etiquette” because she wanted a female scribe for her foundation. Peirce’s language suggests that it was Hürrem alone who bolstered women’s opportunities, yet she does not present any evidence that Hürrem introduced or influenced any social or political reforms for women of the time. Yet perhaps most erroneous is Peirce’s claim that credits Hürrem with the start of “a more peaceable system of identifying the next sultan”. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Following their Hürrem’s death, her sons Selim & Bayezid became entangled in a civil war that ultimately ended with the deaths of Bayezid & his children. Even in the absence of prolonged violence, subsequent secession crises of the sixteenth century were resolved through the execution of the new sultan’s brothers, including infants. It was only with the ascent of thirteen-year-old Ahmed in 1603 that this tradition was set aside for dynastic concerns, although the practice of fratricide did not cease entirely.

When Peirce isn’t falling over to frame Hürrem as a wonder woman, she dismisses those who stood in opposition to her ascent, such as Mahidevran, Süleyman’s previous consort & mother of his firstborn son, Mustafa. Peirce takes a dim view of Mahidevran, presenting her as a jealous woman who needed to be reminded of her duties as mother of a prince. She is depicted a woman worried about losing a man’s favor, rather than a woman who, by all historical accounts, was deeply concerned for her son’s future. Early in Süleyman’s reign, the ambassador Pietro Bragadin reported that Mustafa was his mother’s “whole joy” at their residence in Istanbul. Later, the crucial role Mahidevran played in supporting her son at his provincial governorships was detailed by visiting diplomats. In 1540, Bassano noted her guidance in “[making] himself loved by the people” at his court in Diyarbakır. Mahidevran’s efforts to protect Mustafa, as well as the bond between mother & son, were observed by Bernardo Navagero in 1553: “[Mustafa] has with him his mother, who exercises great diligence to guard him from poisoning & reminds him every day that he has nothing else but this to avoid, & it is said that he had boundless respect & reverence for her.”

Ibrahim Pasha is another figure disparaged by Peirce’s negative bias. A friend from Süleyman’s youth who quickly ascended to the rank Grand Vizier, Ibrahim was not only a skilled & cultured diplomat admired by his counterparts in Europe, but a talented administrator & commander. Eric R. Dursteler writes, “During this time, by all accounts, Ibrahim ruled the day-to-day affairs of the empire effectively. Süleyman seems to have been content to give Ibrahim nearly unlimited power & autonomy in running the Ottoman state, & all matters of any significance passed directly through his hands. [...] If Ibrahim's initial ascent was due to his personal ties to Süleyman, in his years as grand vizier, he proved himself a capable diplomat & an effective political & military leader. In 1524, Süleyman sent Ibrahim to Egypt to restore order following an uprising led by a rebellious Ottoman official sent to rule the earlier conquered province. Ibrahim reorganized legal & fiscal institutions, punished mutinous officials & subjects with severity, established schools, restored mosques, &, by all accounts, restored peace & order to the region.”

Conversely, Peirce describes Ibrahim as “dispensable”, implies that he was holding Süleyman back from achieving his greatest accomplishments, & states “other minds were better suited” to administer the empire as Grand Vizier. When comparing her portrayal of Ibrahim to that of Rüstem Pasha, Mihrimah Sultan’s husband - & Hürrem’s son-in-law - Peirce’s bias becomes clear. She fawns over Rüstem while being completely dismissive of Ibrahim.

Finally, there is Mustafa: the son of Hürrem’s rival Mahidevran & Süleyman’s oldest living son. Empress paints Mustafa as a brat, calling him “a proud child whose sense of entitlement was apparently both acute & insecure." Peirce recounts an ambassadorial report describing the young prince’s jealousy over his father’s relationship with Ibrahim - a story she previously featured in Harem: ‘The sultan sent İbrahim the gift of a beautiful saddle for his horse with jewels & all; & Mustafa, aware of this, sent word to İbrahim to have one like it made for him ; [İbrahim] understood this & sent him the said saddle, & said to him, ‘now listen, if the sultan learns of this, he will make you send it back.”

Peirce’s two treatments of the same story is telling. In Harem, the account illustrates “İbrahim’s kindly patience in soothing the child Mustafa’s jealousy of his father’s affection for his favorite”, with Peirce noting that the relationship “seems to have consolidated” over time - particularly with the emergence of his half-brothers as a greater threat. In Empress, on the other hand, Peirce only concludes that such incidents “may simply reflect a jealousy on Mustafa’s part of anyone close to his father” without mention of the relationship improving, nor of Mustafa recognizing his true rivals to survival.

Whenever Peirce describes Mustafa’s intelligence & his worthiness, she emphasizes that these are the opinions of his contemporaries. It’s as though she wants to disagree, but can’t because historical evidence only points to Mustafa being how he is remembered to be: an intelligent & a worthy heir to the throne. Mustafa was the clear favorite among the people & the army. In Harem, Peirce notes that “Mustafa was universally desired to follow his father to the throne” according to Venetian reports in 1550 & again in 1552. He was more popular than Selim or Bayezid, Hürrem’s living sons who were contenders to the throne. Mehmed, Hürrem’s firstborn, could have been a match for Mustafa had he lived longer, but in the absence of evidence this is mere speculation.

Mustafa’s execution did indeed stain Hürrem’s name. She & Rüstem Pasha were blamed by contemporaries for orchestrating the downfall of the beloved heir apparent. Peirce predictably sets out to clear Hürrem’s name & exonerate her of involvement in the tragedy, but instead of focusing on a lack of hard evidence, she illogically places blame on Mustafa for his own demise. Writing that previous historians studying the topic “largely failed to consider Mustafa’s part in the affair”, Peirce points out the prince’s popularity & that people were already hailing him as “sultan” - something Süleyman would undoubtedly find threatening. Perhaps Mustafa was the victim of his own success, but it would be deeply unfair to blame him for meriting praise & adoration from others, which could only be earned through excelling in his princely duties.

Had Mustafa won the throne after Süleyman died, Ottoman tradition would dictate the deaths of Hürrem’s sons - even Cihangir, said to be fond of his eldest half-brother. According to Navagero, Süleyman reminded Cihangir of this reality, warning his son that “Mustafa will become the sultan & will deprive [you & your brothers] of your lives.” Per the Ottoman practice of institutionalized fratricide, someone would have to die.

Beyond the fact that her sons would face near-certain death had he ascended the throne, a victory for Mustafa would deprive Hürrem of power, leaving her to face the fate that had befallen Mahidevran after her son’s death: destitute & cast aside. As Thys-Senocak explained in [b:Ottoman Women Builders: The Architectural Patronage of Hadice Turhan Sultan|514467|Ottoman Women Builders The Architectural Patronage of Hadice Turhan Sultan|Lucienne Thys-Senocak|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1359624052s/514467.jpg|502432]: “Unlike her European counterparts, the prestige & political legitimacy that an Ottoman valide possessed was derived from her position as the mother of the reigning sultan, rather than through her position as the widow of the deceased sultan [...] Once the father of her son was dead, the valide’s sole source of power & legitimation was through her son, the reigning sultan.” If Mustafa took the throne after Süleyman’s death, Hürrem would have lost not only her sons, but also her status.

The fate of a mother was thus closely bound to the survival of her son. It was not only a mother’s duty to ensure that her son was a contender to the throne, but through his mother’s influence that he survived. A prince’s mother was his mediator, his guardian, his most steadfast ally; it was she who sought to safeguard him from potentially hostile forces, including his own father. While imperial lalas (tutors) ensured that a prince was prepared to take the throne, it was the mother who acted as “an effective agent for her son through her connections with the imperial court, her wealth, & her status as a royal consort & as the most honored person at the provincial court after her son.”

Hürrem, however, did not accompany her sons to their provincial governorships to fulfill the principal role of a prince’s mother. Once again bucking established practice, she remained in Istanbul with Süleyman during this time save for the occasional visit.

Herein lies the irony of Peirce’s Hürrem. Only remotely involved with her sons’ provincial careers, painting Hürrem as an innocent flower who never intrigued at court would mean she did nothing to protect, promote, or prepare them at one of the most crucial points of their lives. If she did not have a hand in anything, whether at sanjak or in Istanbul -- not even to eliminate their biggest competition -- what did Peirce’s Hürrem do to ensure her sons’ success and survival? It is only in the epilogue of Empress that she briefly notes Hürrem’s involvement in ensuring one of her sons received aid he might need. Nevertheless, in the quest to exonerate her subject, Peirce inadvertently makes it seem Hürrem neglected her chief responsibility as mother of the sultanate’s heirs. Even with multiple sons and no precedent to follow, one would think she would’ve done anything to help or protect them -- and by extension, herself. Yet Peirce provides no evidence or examples of Hürrem’s involvement in educating or preparing her sons for rulership.

Ultimately, Empress of the East only does Hürrem a disservice by presenting her as a proto-feminist, empowered heroine r