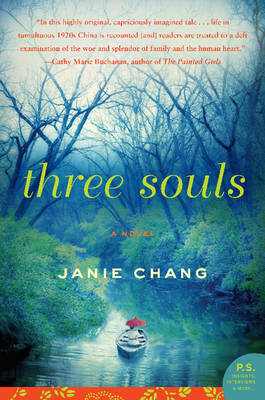

nannah

Written on Jun 2, 2022

Content warnings:

- pedophilia

- substance addiction

- fatphobia

Representation:

- all characters are Chinese

- one secondary character is a gay/bi man

It’s 1935 China and Leiyin has just died, but she and her three souls (yang, yin, and hun) can’t pass into the afterlife. They all must watch her memories to understand what she had done in life to learn what she can do now to make amends. Unfortunately, if she can’t fix the damage soon and ascend to the afterlife, she’ll lose her three souls and wander the world as a mad, hungry ghost.

This is a very easy-to-devour novel and one that kept me up into the well night/morning, despite it not being very action packed. I can’t quite explain it … it’s just very addicting! By far the first half (3/4ths?) is the better part of the story, when Leiyin and her souls relive her memories to find out what it was she’d done that was keeping her in limbo. There’s a clear goal, it’s immediate, and not only that, but we’re also experiencing young Leiyin’s problems and goals as well. Once we learn how Leiyin dies, this drive is lost, and the plot doesn't feel as immediate.

What I also love about this first half--and something I wish would have been explored deeper--is that it shows young Leiyin as a very Western-like protagonist in the way she acts and thinks, and this ultimately leads to her being barred from the afterlife. In a typical US YA novel, she’d be some standard heroine who’d do these same actions--such as disobeying her father multiple times to try to sneak off with her lover instead of being in an arranged marriage, even roping her sister in on an escape attempt--and everything would turn out okay, the father would ultimately understand it’s what she needed to do, hurray individualism, etc. But here, when Leiyin’s choices end up hurting those she loves, their pain is what gets the focus. It’s why she can’t move on.

But there were a couple things that made the reading experience less pleasurable for me. Most noticeably, translating most of the Chinese honorifics. It made dialogue sound horribly awkward and stilted: “Why don’t you come, Eldest Brother”; “Second Son, I approve”; “Consider yourself chaperoned, Third Sister”, etc. And yet a couple honorifics were kept untranslated, like Gong Gong (father-in-law). I promise, we can handle honorifics! Or, at least, we should be able to handle honorifics or names/titles/words in other languages without pitching a fit. There are even some books, like The Firekeeper’s Daughter by Angeline Boulley where no glossary, footnotes, or explanations are provided for readers unfamiliar with the Ojibwe language (the author didn’t want to pander to white readers). Anyway, most importantly, translating the honorifics compromised the sound of the dialogue in this book.

The last thing I have to say is that I wonder why the author chose to make the epilogue an epilogue rather than part of the last chapter (or a separate chapter), because it doesn’t exactly feel like an epilogue, and the previous chapter ending is a terrible way to end the story as is.

But overall, this book is a great read, and I look forward to seeing what else Janie Chang writes/has written!