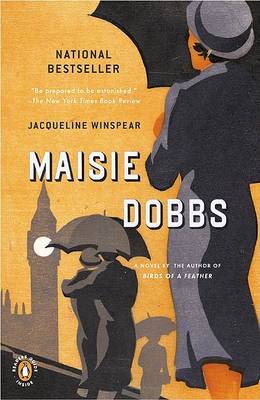

brokentune

Written on Sep 23, 2019

I know, I have issues with historical fiction. I fully acknowledge this and I give books quite a bit of the benefit of my doubt for that exact reason.

However, let's take a look at a paragraph from Maisie Dobbs that has impressed me particularly:

Once across the bridge, Maisie descended into the depths of Westminster underground railway station and took the District Line to Charing Cross station. The station had changed names back and forth so many times, she wondered what it would be called next. First it was Embankment, then Charing Cross Embankment, and now just Charing Cross, depending upon which line you were traveling. At Charing Cross she changed trains, and took the Northern Line to Goodge Street station, where she left the underground, coming back up into the sharp morning air at Tottenham Court Road. She crossed the road, then set off along Chenies Street toward Russell Square. Once across the square, she entered Guilford Street, where she stopped to look at the mess the powers that be had made of Coram’s Fields. The old foundling hospital, built by Sir Thomas Coram almost two hundred years before, had been demolished in 1926, and now it was just an empty space with nothing to speak of happening to it. “Shame,” whispered Maisie, as she walked another few yards and entered Mecklenburg Square.

Named in honor of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, who became queen consort upon her marriage to George III of England, the gracious Georgian houses of the square were set around a garden protected by a wrought-iron fence secured with a locked gate. Doubtless a key to the lock was on a designated hook downstairs at the Davenham residence, in the butler’s safekeeping. In common with many London squares, only residents had access to the garden.

Maisie jotted a few more lines in her notebook, taking care to reflect that she had been to the square once before, accompanying Maurice Blanche during a visit to his colleague, Richard Tawney, the political writer who spoke of social equality in a way that both excited and embarrassed Maisie. At the time it seemed just as well that he and Maurice were deep in lively conversation, so that Maisie’s lack of ease could go unnoticed.

While waiting at the corner and surveying the square, Maisie wondered if Davenham had inherited his property. He seemed quite out of place in Mecklenburg Square, where social reformers lived alongside university professors, poets, and scholars from overseas. She considered his possible discomfort, not only in his marriage but in his home environment. As Maisie set her gaze on one house in particular, a man emerged from a neighboring house and walked in her direction. She quickly feigned interest in a window box filled with crocus buds peeking through moist soil. Their purple shoots seemed to test the air to see if it was conducive to a full-fledged flowering. The man passed. Maisie still had her head inclined toward the flowers when she heard another door close with a thud, and looked up.

The impression is not a good one. You see, the reason this section particularly stuck with me is that I have a particular soft spot for Mecklenburgh Square. It's where Sayers lived when she penned the first Wimsey novel. It's also where Sayers establishes her other main character, Harriet Vane. Apart from Sayers, there are numerous other writers of note that lived in this area. So, when I was in London earlier this year, I made a point of visiting the place.

Not only is it "Mecklenburgh", with an "h", rather than "Mecklenburg" (unless you're referring to Sayers' fictionalised "Mecklenburg Sq."), but most of the houses have a gap between the windows and the pavement, which is fenced off.

The buildings don't really have windowsills wide enough to hold window boxes - and this is the usual style all around the square from what I remember. As the buildings wound be the same as described in Maisie Dobbs' setting, I doubt this has changed since 1929.

There are window boxes, but if a person is standing near one, the person would be standing at an entrance. And staring at a window box standing at the front door of a house without seeming to want to enter or knock...Well, I'm sorry but I can't think of many things that look even more suspicious.

Also, why do we need the lessons in London tube stations and the history of the square itself? What has any of this to do with the story?

This sort of Oh-look-how-much-research-I've-done-info-dumping has happened throughout the book so far, and of course we also have the dreaded descriptions of fashion. I can't stand descriptions of fashion details that have no relevance to the scene.

Like this one:

“I see. Mr. Davenham, this is a delicate situation. Before I proceed, I must ask for you to make a commitment to me—”

“Whatever do you mean?”

“A commitment to your marriage, actually. A commitment, perhaps, to your wife’s well-being and to your future.”

Christopher Davenham stirred uneasily in his chair and folded his arms.

“Mr. Davenham,” said Maisie, looking out of the window, “it’s a very fine day now, don’t you think? Let’s walk around Fitzroy Square. We will be at liberty to speak freely and also enjoy something of the day.”

Without waiting for an answer, Maisie rose from her chair, took her coat from the stand, and passed it to Christopher Davenham who, being a gentleman, stifled his annoyance, took the coat, and held it out for Maisie. Placing her hat upon her head and securing it with a pearl hatpin, Maisie smiled up at him. “A walk will be lovely.”

So, here is a client with a tricky problem, and we switch the focus from the conversation to a hat pin? WTF?

And don't get me started on Maisie's trying to fix the man's marriage...how well would this have gone down in 1929...unless you're Parker Pyne, Agatha Christie's famous "detective of the heart"?

So, yeah, this book so far lacks all credibility for me and the over-indulgence in pointless detail is distracting from any of the interesting aspects of the novel such as how people dealt with war wounds - physical and mental. There was much promise in this, but little has been made of it so far.

In short, this is an example of why I prefer non-fiction history or, particularly with respect to book set between 1900 and 1945, books written at the actual time.