nannah

Written on Jun 10, 2022

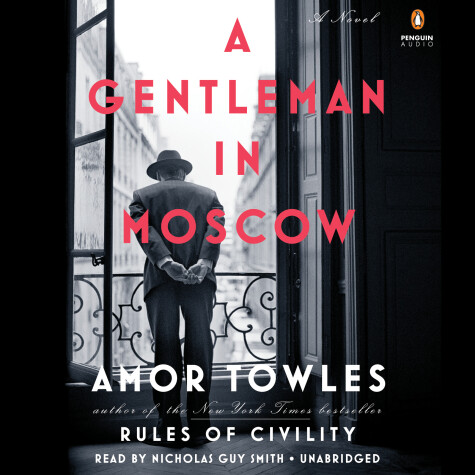

Charming but almost unbearably twee, A Gentleman in Moscow is the sugar-coated account of a wealthy aristocrat who is remarkably allowed to live by the Bolsheviks and sentenced to live out the rest of his life in a fancy hotel in 1922 Russia.

Content warnings:

- cissexism

- romani slur

- suicide

Representation:

- N/A

Count Alexander Rostov is condemned as an unrepentant aristocrat by the Bolsheviks, but a revolutionary poem he wrote years ago saves his life. Instead of being shot, he’s put under “house arrest” in the Metropol, a fancy hotel in Moscow. Despite a rocky beginning, he begins to think of himself as the “luckiest man in the world” after creating friendships with the guests and staff.

Okay, so I was completely charmed by maybe the first 150-200 pages by the Count and the gorgeous prose. The Count quickly became a favorite character when he discerned the musical key of his bedsprings by jumping on them -- but my love for him didn’t last. He was just so gratingly good at everything, and he thought it his duty to educate everyone, even interrupting people’s dinners to do so (which doesn’t really strike me as something that’s particularly gentlemanly, but what do I know). His character arc is fairly flat too, as are the other character arcs, which in a 450-page book with very little plot, is incredibly aggravating.

I’m aware of what this book is about and what it’s trying to say … and it having been published (and/or popular) when much of the world was in lockdown from the pandemic makes its themes that much more meaningful. So many people just wanted an escape, something hopeful and lovely, and this book is all of that. Reading about the Count, also in a “lockdown” of sorts, finding and making his own happiness in the small things is very satisfying.

But knowing that it was all happening in the comfy, plush Metropol while out in the rest of Russia most people were dying and starving and suffering (courtesy of a few footnotes written in the same cheerful style) made me very uncomfortable. And it felt like a very ugly choice to have the focus be on situations such as the Count lamenting over the fact that because of the awful Bolsheviks, all the bottles of wine in his favorite Metropol restaurant are now unlabeled (how will he ever find the right one to pair with his fancy meal now?!).

What really began to bother me about three-fourths of the way through the book was the way the Count, who already seemed a bit too talented and polished and perfect and adored, only seemed to befriend people who were also wildly talented. We have his lover, a famous actress; his daughter, a piano prodigy; and the two close friends he makes at the hotel: a world-class chef and the skilled maître d’. But we never really get a close-enough look at them to see any flaws--or any deeper characterization--besides what can be used to offer the Count or enrich his own characterization.

The Count did go through some growth, which … thank god, because he was incredibly selfish, full of himself, and insufferable throughout most of the novel. He did learn to live a little more, risk a little more, etc., but while that might work in a story set somewhere else, it was baffling here. His friends at the restaurant where he eventually worked had tough lives outside the Metropol (shown via a few sections in their povs--which were some of my favorite parts), but the Count never asked about their lives or showed any concern for them or even the outside world at all--until it directly concerned him or his life, of course.

But all this isn’t to say I absolutely hated everything about this book. The writing is superb. Amor Towles knows what he’s doing there. The story was never boring to read, even if it progressed at a slow pace, because of that. I loved experiencing his writing style.

I also adored the beekeeper, even if his part was very small. The two scenes when the Count went up to see him, a character who was so very different from who he was, stuck with me the most. They’re the most vivid scenes that come to mind when I think of the book and what I liked.

I just wished there would be some kind of commentary or contrast made between the Count’s sheltered and almost fantasy-like world inside the Metropol and the harsh reality outside it. Throughout the entire novel, the Count never once thought about his past or his class with a critical eye. But I get it: that’s not what this book was about. It's obviously found a loving audience, which is great, but it didn’t resonate with me.

Content warnings:

- cissexism

- romani slur

- suicide

Representation:

- N/A

Count Alexander Rostov is condemned as an unrepentant aristocrat by the Bolsheviks, but a revolutionary poem he wrote years ago saves his life. Instead of being shot, he’s put under “house arrest” in the Metropol, a fancy hotel in Moscow. Despite a rocky beginning, he begins to think of himself as the “luckiest man in the world” after creating friendships with the guests and staff.

Okay, so I was completely charmed by maybe the first 150-200 pages by the Count and the gorgeous prose. The Count quickly became a favorite character when he discerned the musical key of his bedsprings by jumping on them -- but my love for him didn’t last. He was just so gratingly good at everything, and he thought it his duty to educate everyone, even interrupting people’s dinners to do so (which doesn’t really strike me as something that’s particularly gentlemanly, but what do I know). His character arc is fairly flat too, as are the other character arcs, which in a 450-page book with very little plot, is incredibly aggravating.

I’m aware of what this book is about and what it’s trying to say … and it having been published (and/or popular) when much of the world was in lockdown from the pandemic makes its themes that much more meaningful. So many people just wanted an escape, something hopeful and lovely, and this book is all of that. Reading about the Count, also in a “lockdown” of sorts, finding and making his own happiness in the small things is very satisfying.

But knowing that it was all happening in the comfy, plush Metropol while out in the rest of Russia most people were dying and starving and suffering (courtesy of a few footnotes written in the same cheerful style) made me very uncomfortable. And it felt like a very ugly choice to have the focus be on situations such as the Count lamenting over the fact that because of the awful Bolsheviks, all the bottles of wine in his favorite Metropol restaurant are now unlabeled (how will he ever find the right one to pair with his fancy meal now?!).

What really began to bother me about three-fourths of the way through the book was the way the Count, who already seemed a bit too talented and polished and perfect and adored, only seemed to befriend people who were also wildly talented. We have his lover, a famous actress; his daughter, a piano prodigy; and the two close friends he makes at the hotel: a world-class chef and the skilled maître d’. But we never really get a close-enough look at them to see any flaws--or any deeper characterization--besides what can be used to offer the Count or enrich his own characterization.

The Count did go through some growth, which … thank god, because he was incredibly selfish, full of himself, and insufferable throughout most of the novel. He did learn to live a little more, risk a little more, etc., but while that might work in a story set somewhere else, it was baffling here. His friends at the restaurant where he eventually worked had tough lives outside the Metropol (shown via a few sections in their povs--which were some of my favorite parts), but the Count never asked about their lives or showed any concern for them or even the outside world at all--until it directly concerned him or his life, of course.

But all this isn’t to say I absolutely hated everything about this book. The writing is superb. Amor Towles knows what he’s doing there. The story was never boring to read, even if it progressed at a slow pace, because of that. I loved experiencing his writing style.

I also adored the beekeeper, even if his part was very small. The two scenes when the Count went up to see him, a character who was so very different from who he was, stuck with me the most. They’re the most vivid scenes that come to mind when I think of the book and what I liked.

I just wished there would be some kind of commentary or contrast made between the Count’s sheltered and almost fantasy-like world inside the Metropol and the harsh reality outside it. Throughout the entire novel, the Count never once thought about his past or his class with a critical eye. But I get it: that’s not what this book was about. It's obviously found a loving audience, which is great, but it didn’t resonate with me.