cornerfolds

Written on Nov 14, 2013

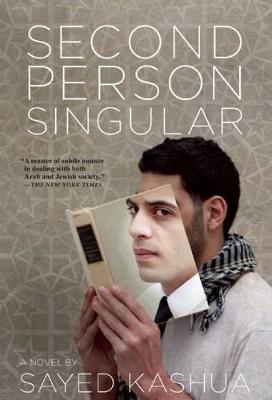

I read this book for my Jewish Studies class because it was the only work of fiction on the list we could choose from. This book was published in April 2012 by Sayed Kashua, an Israeli Arab who lives in Jerusalem. I think that Kashua’s nationality and background had a large role to play in the writing of this book, since both main characters are of similar background.

The book follows two main storylines – that of a married Arab lawyer and a single Arab social worker. The lawyer, after purchasing a book in a used bookstore, finds a note in his wife’s handwriting stating that she enjoyed her night. The lawyer immediately loses his mind trying to figure out whom the note was addressed to, thinking up all kinds of scenarios in which is wife must have been unfaithful to him. After using the resources at his disposal, he finds out that the note was meant for the social worker, though he is now using an assumed name, Yonatan – the name of the incapacitated man he now cares for in his current career. At the end of the book, the lawyer confronts Yonatan and finds out he does not even remember his wife and that the note was written before the lawyer and his wife had even begun dating.

Second Person Singular is meant, primarily, to shed light on the Arab situation amongst a Jewish population in Israel. The discrimination they face, whether bad or, as seen in the school of photography that Yonatan is eventually accepted to, good. When Yonatan applies to the school, he assumes a Jewish identity, stating that the school automatically admits Arabs because there must always be an Arab for each class – a kind of forced assimilation, if you will. Citizens are asked to show their papers in different settings and, though nationality is no longer required to be declared, there is still clear discrimination against the Arab population and favoring of the Jews.

We are shown the inside workings of an Arab marriage, though I think the lawyer’s might be a little extreme, and we also see that gender roles in this part of the world are not necessarily what stereotypes may have led us to believe, though there does seem to be an underlying way of thinking that still has not been completely weeded out, even in the 21st century. In the way Kashua writes, it is clear that there is a lot of internal conflict, even within a supposedly liberal Arab about the way a woman should behave. Though the lawyer has stated that he would even be okay with marrying a woman who was not a virgin, he is enraged by the thought that his wife may have even loved a man before she met him, to the point where he repeatedly calls her a whore and thinks of ways to kill her. Despite his claims to liberalism, he is still, deep down, tied to the “old ways.”

I thought this book was overly dramatic, especially in the way the lawyer reacted to his wife’s note. I do feel that the way Arab life was represented in the book may have been somewhat biased based on the author’s nationality. I would not read this book again and I probably wouldn't recommend it to anyone. It was incredibly boring and took me nearly two months to get through. Steer clear.