Africa List

1 total work

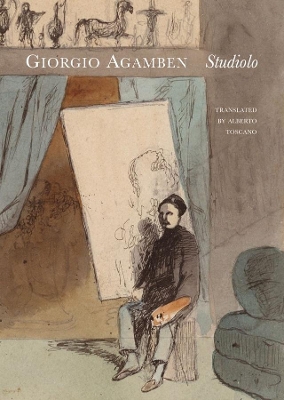

A brief study of select Western art from Italy's foremost philosopher.

In Renaissance palaces, the studiolo was a small room to which the prince withdrew to meditate or read, surrounded by paintings he particularly loved. This book is a kind of studiolo for its author, Giorgio Agamben, as he turns his philosophical lens on the world of Western art.

Studiolo is a fascinating take on a selection of artworks created over millennia; some are easily identifiable, others rarer. Though they were produced over an arc of time stretching from 5000 BCE to the present, only now have they achieved their true legibility. Agamben contends that we must understand that the images bequeathed by the past are really addressed to us, here and now; otherwise, our historical awareness is broken. Notwithstanding the attention to details and the critical precautions that characterize the author's method-they provoke us with a force, even a violence, that we cannot escape. When we understand why Dostoevsky feared losing his faith before Holbein's Body of the Dead Christ, when Chardin's Still Life with Hare is suddenly revealed to our gaze as a crucifixion or Twombly's sculpture shows that beauty must ultimately fall, the artwork is torn from its museological context and restored to its almost prehistoric emergence. These artworks are beautifully reproduced in color throughout Agamben's short but significant addition to his scholarly oeuvre in English translation.

In Renaissance palaces, the studiolo was a small room to which the prince withdrew to meditate or read, surrounded by paintings he particularly loved. This book is a kind of studiolo for its author, Giorgio Agamben, as he turns his philosophical lens on the world of Western art.

Studiolo is a fascinating take on a selection of artworks created over millennia; some are easily identifiable, others rarer. Though they were produced over an arc of time stretching from 5000 BCE to the present, only now have they achieved their true legibility. Agamben contends that we must understand that the images bequeathed by the past are really addressed to us, here and now; otherwise, our historical awareness is broken. Notwithstanding the attention to details and the critical precautions that characterize the author's method-they provoke us with a force, even a violence, that we cannot escape. When we understand why Dostoevsky feared losing his faith before Holbein's Body of the Dead Christ, when Chardin's Still Life with Hare is suddenly revealed to our gaze as a crucifixion or Twombly's sculpture shows that beauty must ultimately fall, the artwork is torn from its museological context and restored to its almost prehistoric emergence. These artworks are beautifully reproduced in color throughout Agamben's short but significant addition to his scholarly oeuvre in English translation.