Native American Resources

1 total work

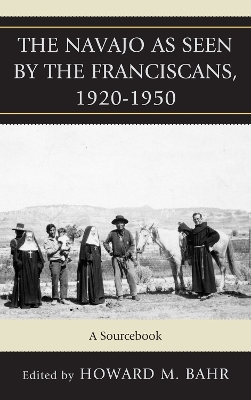

Continuing where the author's previous volume left off, The Navajo as Seen by the Franciscans, 1920-1950: A Sourcebook picks up the story of one of the great cultural confluences in American history. It reflects, from the standpoint of the Franciscan missionaries, the joining of two starkly different ways of life. The years between 1920 and 1950 were not tame times for the Navajos. They were faced with epidemics, a federal education policy that sometimes fostered "child stealing," the era of stock-reduction and the attendant impoverishment of the entire tribe, Navajo political reorganization, a failed mid-1930s attempt to shift Navajo education from boarding schools to day schools, and continual deep underfunding of Navajo programs until the U.S. Congress, spurred by unprecedented media attention to Navajo poverty, in 1950 passed the Navajo-Hopi Rehabilitation Bill.

Consisting of both primary—first-hand accounts of families visited, events observed, and actions taken in which the writer participated directly—and secondary—the historical record based on the writings of others—sources of Franciscan writings, the Franciscan literature sampled in this book mirrors the Navajo of the early and mid-20th century. The texts created by the Franciscans and their associates in the course of their labors, constitute a seldom-quoted, little-read, generally difficult-to-access literature of enormous importance to the history of Navajo-white relations. Many of the Franciscans who came to the reservation stayed there for their entire working lives, spending decades learning the Navajo language and serving the population. Their writings to each other, whether published in mission journals or preserved in their correspondence, present an intimate view of Navajo life as observed by missionaries dedicated to serving the Navajo, burying their dead, serving as their advocates with the institutions of white America, teaching their children, and trying themselves to learn the Navajo language.

Consisting of both primary—first-hand accounts of families visited, events observed, and actions taken in which the writer participated directly—and secondary—the historical record based on the writings of others—sources of Franciscan writings, the Franciscan literature sampled in this book mirrors the Navajo of the early and mid-20th century. The texts created by the Franciscans and their associates in the course of their labors, constitute a seldom-quoted, little-read, generally difficult-to-access literature of enormous importance to the history of Navajo-white relations. Many of the Franciscans who came to the reservation stayed there for their entire working lives, spending decades learning the Navajo language and serving the population. Their writings to each other, whether published in mission journals or preserved in their correspondence, present an intimate view of Navajo life as observed by missionaries dedicated to serving the Navajo, burying their dead, serving as their advocates with the institutions of white America, teaching their children, and trying themselves to learn the Navajo language.