The Margellos World Republic of Letters

4 primary works

Book 1

"Michel Leiris is the author of the most significant and arresting work of autobiography to have been written in the twentieth century."--John Sturrock "For me his work is not only a document that enriches our knowledge of man, but also a personal testament that touches me deeply."--Francis Bacon ' Scratches' is the first volume in Michel Leiris's monumental four-volume autobiography, 'Rules of the Game.' In this volume, the celebrated French writer examines his inventory of memories, explores the language of his childhood, weaves anecdotes from his private life with his old and recent ideas. In the end, he so mercilessly scrutinizes what was familiar that its familiarity drops away and it blossoms into something exotic. As Leiris recollects his childhood, his father's recording machine becomes a miraculous object and the letters of the alphabet--from A (or the double ladder of a house painter) to I (a soldier standing at attention) to X (the cross one makes on something whose secret one will never penetrate)--come magically to life.

Also here are evocations of Paris under the occupation, his journey to Africa, and meditations on his fear of death, which he tried to exorcise through his autobiographical writings.

Also here are evocations of Paris under the occupation, his journey to Africa, and meditations on his fear of death, which he tried to exorcise through his autobiographical writings.

Book 2

"I read with fervor the literary works of Michel Leiris and in particular the four volumes of 'Rules of the Game'...He is incontestably one of the greatest writers of the century."--Claude Livi-Strauss In this second volume of his acclaimed four-volume autobiography, 'Rules of the Game'--now available for the first time in English--Leiris comes to terms with self-reflection as disillusionment. In the midst of doubts about his own motives in writing an autobiography, he recalls that life, after all, has delights worth remembering: sights at the end of the world and the beginning of time, palm trees, breadfruit trees, colossal ferns. But even these things surrounded people living in miserable conditions. What could be said of human life, or of his own life, when his memory was unreliable, his eyesight failing, his mood in the bottom of a hole?

"In Leiris's' Rules of the Game' Volume 2, I found again those qualities that had riveted me in Volume 1: those spirals of words coiling in on themselves and unrolling again into infinity, drilling onto the abysses of the past and the heart, yet glittering there in broad daylight, reflecting from image to image toward a secret that vanishes at the very instant it seems it must appear, the search having no other outcome than itself in the slow revolution of its thousand mirrors."--Simone de Beauvoir

"In Leiris's' Rules of the Game' Volume 2, I found again those qualities that had riveted me in Volume 1: those spirals of words coiling in on themselves and unrolling again into infinity, drilling onto the abysses of the past and the heart, yet glittering there in broad daylight, reflecting from image to image toward a secret that vanishes at the very instant it seems it must appear, the search having no other outcome than itself in the slow revolution of its thousand mirrors."--Simone de Beauvoir

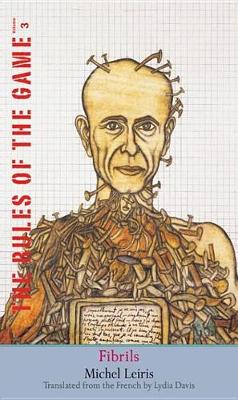

Book 3

A major publishing event: the third volume of Michel Leiris's renowned autobiography, now available in English for the first time in a brilliant translation by Lydia Davis

A beloved and versatile author and ethnographer, French intellectual Michel Leiris is often ranked in the company of Proust, Gide, Sartre, and Camus, yet his work remains largely unfamiliar to English-language readers. This brilliant translation of Fibrils, the third volume of his monumental autobiographical project The Rules of the Game, invites us to discover why Levi-Strauss proclaimed him "incontestably one of the greatest writers of the century."

Leiris's autobiographical essay, a thirty-five-year project, is a primary document of the examined life in the twentieth century. In Fibrils, Leiris reconciles literary commitment with social/political engagement. He recounts extensive travel and anthropological work, including a 1955 visit to Mao's China. He also details his suicidal "descent into Hell," when the guilt over an extramarital affair becomes unbearable. A ruthless self-examiner, Leiris seeks to invent a new way of remembering, probe the mechanisms of memory and explore the way a life can be told.

A beloved and versatile author and ethnographer, French intellectual Michel Leiris is often ranked in the company of Proust, Gide, Sartre, and Camus, yet his work remains largely unfamiliar to English-language readers. This brilliant translation of Fibrils, the third volume of his monumental autobiographical project The Rules of the Game, invites us to discover why Levi-Strauss proclaimed him "incontestably one of the greatest writers of the century."

Leiris's autobiographical essay, a thirty-five-year project, is a primary document of the examined life in the twentieth century. In Fibrils, Leiris reconciles literary commitment with social/political engagement. He recounts extensive travel and anthropological work, including a 1955 visit to Mao's China. He also details his suicidal "descent into Hell," when the guilt over an extramarital affair becomes unbearable. A ruthless self-examiner, Leiris seeks to invent a new way of remembering, probe the mechanisms of memory and explore the way a life can be told.

Book 4

The fourth and final volume of Michel Leiris’s renowned autobiography, now available in English for the first time, translated by Richard Sieburth

“Reading Frail Riffs, appearing in English nearly fifty years after its initial French publication, I realize how much our attraction to autobiography owes to Leiris . . . a quiet virtuoso of French prose.”—Alice Kaplan, New York Review of Books

Ex-surrealist and maverick anthropologist Michel Leiris (1901–1990) crafted his multivolume autobiography over the course of thirty-five years, profoundly influencing generations of French writers, from Sartre and Beauvoir to Modiano and Ernaux. In this fourth and final volume, Richard Sieburth completes the project of bringing Leiris’s monumental experiment in self-portraiture into English.

With wit and playfulness, Leiris assembled a scrapbook of fragments—journal extracts, travel notes, transcriptions of dreams, poems—to document the vagaries of a life committed to the difficult marriage of poetry and revolutionary politics, which he witnessed firsthand in Mao’s China, Castro’s Cuba, and on the Paris streets in May ’68.

Frail Riffs is a jazz improvisation on the twilight of a life, at once a painstaking self-examination and a chronicle of a century. As Leiris wrote, it is “neither a private diary nor a formal work, neither an autobiographical narrative nor a work of the imagination, neither prose nor poetry, but all this at the same time. . . . A perpetual work in progress.”

“Reading Frail Riffs, appearing in English nearly fifty years after its initial French publication, I realize how much our attraction to autobiography owes to Leiris . . . a quiet virtuoso of French prose.”—Alice Kaplan, New York Review of Books

Ex-surrealist and maverick anthropologist Michel Leiris (1901–1990) crafted his multivolume autobiography over the course of thirty-five years, profoundly influencing generations of French writers, from Sartre and Beauvoir to Modiano and Ernaux. In this fourth and final volume, Richard Sieburth completes the project of bringing Leiris’s monumental experiment in self-portraiture into English.

With wit and playfulness, Leiris assembled a scrapbook of fragments—journal extracts, travel notes, transcriptions of dreams, poems—to document the vagaries of a life committed to the difficult marriage of poetry and revolutionary politics, which he witnessed firsthand in Mao’s China, Castro’s Cuba, and on the Paris streets in May ’68.

Frail Riffs is a jazz improvisation on the twilight of a life, at once a painstaking self-examination and a chronicle of a century. As Leiris wrote, it is “neither a private diary nor a formal work, neither an autobiographical narrative nor a work of the imagination, neither prose nor poetry, but all this at the same time. . . . A perpetual work in progress.”