MIT Press

4 total works

"Let us listen to the counsels of American engineers. But let us beware of American architects!" declared Le Corbusier, who like other European architects of his time believed that he saw in the work of American industrial builders a model of the way architecture should develop. It was a vision of an ideal world, a "concrete Atlantis" made up of daylight factories and grain elevators.In a book that suggests how good Modern was before it went wrong, Reyner Banham details the European discovery of this concrete Atlantis and examines a number of striking architectural instances where aspects of the International Style are anticipated by US industrial buildings.

The Architecture of H. H. Richardson and His Times, second edition

by Henry-Russell Hitchcock

His heritage was the romantic generation that had contemptuously renounced the austerity of the classical revival and, in the search for stylistic stimulation, had borrowed indiscriminately from the rich bazaar of historic and exotic styles, the Gothic, Italianate, Norman, Byzantine. By the time Richardson had completed his education at Harvard and at the École des Beaux-Arts, this mixed architectural diet had played havoc with the American taste.

In his maturity he developed a personal style that resolved the dilemma in which he found himself: his own good taste and judgment demanded utility, spatial tangibility, function; his public demanded pictorial surface effects. His reconciliation of these disparities resulted in his finest works: Trinity Church, Boston; the Marshall Field Wholesale Store, Chicago; the Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail, Pittsburgh; Sever Hall, Cambridge.

At the time of his death technological advances had made the skyscraper feasible, and in the succeeding years architectural form was virtually dictated by these advances. Richardson's mastery of traditional composition, mortar, polychromy, and ornament was largely forgotten. Today in the search for aesthetic expression of fine materials and (integral) ornament, Richardson's work is relevant once more for practical as well as historical purposes.

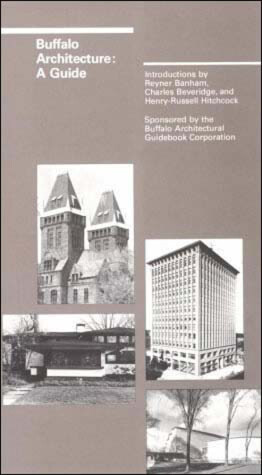

Buffalo Architecture

by Reyner Banham, Charles Beveridge, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, and Buffalo Architectural Guidebook Corporation

Buffalo's rich architectural and planning heritage has attracted the attention of several prominent historians, whose work here is accompanied by over 250 illustrations and photographs.

For its size, the city of Buffalo, New York, possesses a remarkable number and variety of architectural masterpieces from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: Adler and Sullivan's Prudential building, H. H. Richardson's massive Buffalo State Hospital, Richard Upjohn's Sr. Paul's Episcopal Cathedral, five prairie houses by Frank Lloyd Wright, and building by Daniel Burnham, Albert Kahn, and the firms of McKim, Mead, and White, and Lockwood, Green and Company, among others.

These structures by prominent "outsiders" served to spur the efforts of local architects, builders, and craftsmen, and all of them built within the context of the city-wide park and parkway system designed by Frederick Law Olmsted. In addition, the city and its environs exhibit representative works by more recent architects, among them Eero and Eliel Saarinen, Walther Gropius, Marcel Breuer, Paul Rudloph, Minoru Yamasaki, and the firm of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill.

Buffalo's rich architectural and planning heritage has attracted the attention of several prominent historians, capable of the challenge of evaluating its significance. Reyner Banham is one of the world's leading authorities on the theory and practice of architecture, and he has written extensively on design in the industrial age (and Buffalo's innovative manufacturing plants and grain elevators are important exemplars of such design). Charles Beveridge, whose essay covers the park and parkway system, is editor of the Olmsted papers at The American University. And Henry Russell Hitchcock is the dean of American architectural historians, and the organizer of a 1940 exhibition on Buffalo's built environment.

Their essays are followed by seven sections that delineate the city's neighborhoods, each provided with a map, neighborhood history, and a full complement of photographs with descriptive building captions. An eighth section, "Lost Buffalo," describes demolished buildings, chief among them Wright's great Larkin administration building, while the remaining sections venture out of town, exploring Erie and Niagara Counties, other parts of Western New York, and southern Ontario.