The Collected Works of Langston Hughes

9 total works

Collected Works of Langston Hughes v. 8; Later Simple Stories

by Langston Hughes

In Volume 8 of The Collected Works of Langston Hughes, the genial Harlem everyman, Jesse B. Semple returns with his more cosmopolitan bar buddy, Ananias Boyd. Social climber Joyce Lane is now Mrs. Jesse B. Semple, and Simple has minimized his flirtatious contacts with other women. Despite these ongoing characters, the later Simple stories are very different from the earlier Simple tales. The later stories evoke the historical and social context within which they were written, a politically dangerous time for the fictional adventures and fantasies of the main characters.

The Later Simple Stories returns to print Hughes's third and fourth Simple collections, Simple Stakes a Claim and Simple's Uncle Sam, along with some episodes Hughes did not include in any of his books. Simple Stakes a Claim was published in 1957, and it reflects the troubled and troublesome era of the Cold War and McCarthy hearings. Simple's Uncle Sam appeared in 1965, and it captures the turbulent decade when black Americans asserted their rights, including the privilege to call themselves "Black" and wear their hair in natural styles. The nonviolent strategies of civil disobedience and the violent strategies of urban rioting had converged to amplify African American voices as they demanded justice.

The innocent humor of the earlier Simple stories is replaced here by new strengths. Remarkably powerful female characters emerge in this volume. We observe Cousin Minnie's self-preservation skills and her willingness to riot to defend her rights as a citizen. We read about Simple's cousin Lynn Clarisse, who is a social activist educated at Fisk University. And we see Joyce herself emerge from her prim niche to display pride and knowledge about her African heritage.

The Later Simple Stories rounds out Hughes's presentation of Jesse B. Semple and the various people of his world. Simple and his foil still make us chuckle, but more important, they make us think. While these episodes often focus on particularities of the times, they also articulate broader truths that remain valuable.

Langston Hughes was among the Harlem Renaissance authors who traveled widely during the 1920s. In the first volume of his autobiography, The Big Sea, covering the years through 1931, Hughes offers recollections of his childhood in Kansas, his high school years in Cleveland, his sojourn with his father in Mexico, and his initial reactions to New York City and Harlem.

Commentaries on the "Black Renaissance" in Harlem and Washington, D.C., are intertwined with recollections of his student years at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, his travels through the South, and his association as a "younger generation" poet with the New York and Harlem literary establishment represented by the magazines Crisis and Opportunity. Personal memories of Jessie Fauset, Countee Cullen, Jean Toomer, W. E. B. Du Bois, Wallace Thurman, Alain Locke, Carter G. Woodson, Vachel Lindsay, A'Lelia Walker, and others are augmented by allusions to such celebrities as Duke Ellington, Florence Mills, Eubie Blake, Florence Embry, Josephine Baker, Bert Williams, Theodore Dreiser, Ethel Barrymore, and Bessie Smith. Hughes addresses such controversial issues as his literary and personal disagreements with Zora Neale Hurston over their play Mule Bone, Carl Van Vechten's problematic novel Nigger Heaven, racial matters at Lincoln University, the Jim Crow laws in the South, and the failures of white patronage. Furthermore, Hughes refers to the sources of a blues poetry aesthetic, his visit to Cuba, and the struggle to complete his first novel, Not without Laughter. A rare autobiographical presentation of the Harlem Renaissance from the perspective of an insider, The Big Sea is a veritable catalog of notables. In addition, it offers a "black perspective" on the expatriate life in Europe during the Jazz Age.

The Collected Works of Langston Hughes v. 3; Poems 1951-1967

by Langston Hughes

The Collected Works of Langston Hughes v. 10; Fight for Freedom and Related Writing

by Langston Hughes

The Collected Works of Langston Hughes v. 5; Plays to 1942 - ""Mulatto"" to ""The Sun Do Move

by Langston Hughes

The Collected Works of Langston Hughes v. 7; Early Simple Stories

by Langston Hughes

The Collected Works of Langston Hughes v. 12; Works for Children and Young Adults - Biographies

by Langston Hughes

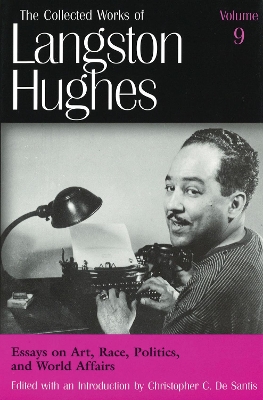

Among the most prolific of American writers, Langston Hughes gained international attention and acclaim in nearly every genre of writing. While scholars and general readers have enjoyed relatively easy access to most of his writings, Hughes's work in one genre "the essay" has gone largely unnoticed. From his radical pieces praising revolutionary socialist ideology in the 1930s to the more conservative, previously unpublished "Black Writers in a Troubled World," which he wrote a year before his death, Hughes used the essay form as a vehicle through which to comment on the contemporary issues he found most pressing at various stages of his career.

Hughes generated some of his most powerful critiques of economic and racial exploitation and oppression through his masterful essays. It was the essay as a literary form that allowed Hughes to document the essential contributions made by African Americans to literature, music, film, and theater, and to chronicle the immense difficulties black artists faced in gaining recognition, fair remuneration, and professional advancement for these contributions. Finally, it was in certain essays that Hughes most fully represented the unique and endearing persona of the blues-poet-in-exile.

Many of the essays and other pieces of short nonfiction included in this volume have long been out of print and will be new to most readers. Through them, Langston Hughes reaffirmed a belief in the political potential of African American writers that remained consistent throughout his forty-six-year professional writing career: "Ours is a social as well as a literary responsibility." Such a belief resounds everywhere in this volume "a true testament of a man committed to the capabilities of language to generate social awareness and, ultimately, to compel social change."