Medieval History and Archaeology

1 total work

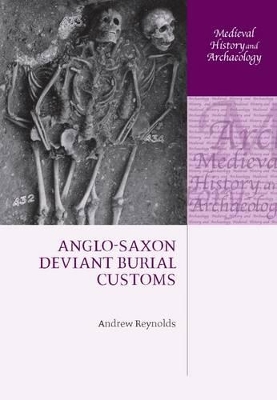

Anglo-Saxon Deviant Burial Customs is the first detailed consideration of the ways in which Anglo-Saxon society dealt with social outcasts. Beginning with the period following Roman rule and ending in the century following the Norman Conquest, it surveys a period of fundamental social change, which included the conversion to Christianity, the emergence of the late Saxon state, and the development of the landscape of the Domesday Book.

While an impressive body of written evidence for the period survives in the form of charters and law-codes, archaeology is uniquely placed to investigate the earliest period of post-Roman society, the fifth to seventh centuries, for which documents are lacking. For later centuries, archaeological evidence can provide us with an independent assessment of the realities of capital punishment and the status of outcasts.

Andrew Reynolds argues that outcast burials show a clear pattern of development in this period. In the pre-Christian centuries, 'deviant' burial remains are found only in community cemeteries, but the growth of kingship and the consolidation of territories during the seventh century witnessed the emergence of capital punishment and places of execution in the English landscape. Locally determined rites, such as crossroads burial, now existed alongside more formal execution cemeteries. Gallows

were located on major boundaries, often next to highways, always in highly visible places.

The findings of this pioneering national study thus have important consequences on our understanding of Anglo-Saxon society. Overall, Reynolds concludes, organized judicial behaviour was a feature of the earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, rather than just the two centuries prior to the Norman Conquest.

While an impressive body of written evidence for the period survives in the form of charters and law-codes, archaeology is uniquely placed to investigate the earliest period of post-Roman society, the fifth to seventh centuries, for which documents are lacking. For later centuries, archaeological evidence can provide us with an independent assessment of the realities of capital punishment and the status of outcasts.

Andrew Reynolds argues that outcast burials show a clear pattern of development in this period. In the pre-Christian centuries, 'deviant' burial remains are found only in community cemeteries, but the growth of kingship and the consolidation of territories during the seventh century witnessed the emergence of capital punishment and places of execution in the English landscape. Locally determined rites, such as crossroads burial, now existed alongside more formal execution cemeteries. Gallows

were located on major boundaries, often next to highways, always in highly visible places.

The findings of this pioneering national study thus have important consequences on our understanding of Anglo-Saxon society. Overall, Reynolds concludes, organized judicial behaviour was a feature of the earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, rather than just the two centuries prior to the Norman Conquest.