The MIT Press

2 total works

According to Paul Shepheard, architecture is the rearranging of the world for human purposes. Sculpture, machines, and landscapes are all architecture-every bit as much as buildings are. In his writings, Shepheard examines old assumptions about architecture and replaces the critical theory of the academic with the active theory of the architect-citizen enamored of the world around him.

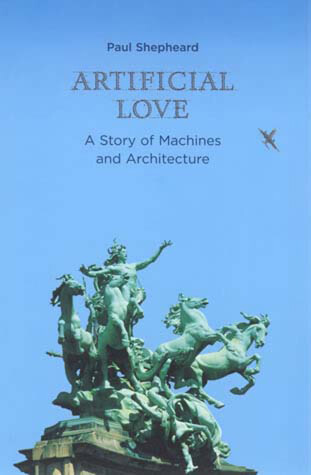

Artificial Love weaves together three stories about architecture into one. The first, about machines as architecture, leads to speculations about technology and the human condition and to the assertion that machines are the sculptures of today. The second story is about the ways that architecture reflects the tribal and personal desires of those who make it. In the West, ideas of community, multiculturalism, and globalization compete furiously, leaving architecture to exist as it always has, as the past in the present. The third story features individual people experiencing their lives in the context of architecture. Here, Shepheard borrows the rhetorical device of Shakespeare's seven ages of man to propose that each person's life imitates the accumulating history of the human species. Shepheard's version of the history of humans is a technological one, in which machines become sculpture and sculpture becomes architecture. For Shepheard, our machines do not separate us from nature. Rather, our technology is our nature, and we cannot but be in harmony with nature. The change that we have wrought in the world, he says, is a wonderful and powerful thing.