Casemate Short History

5 total works

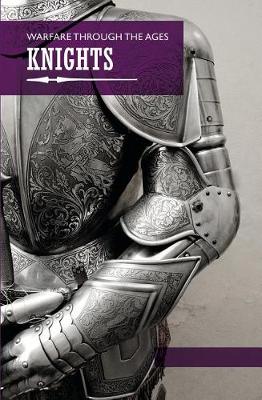

Originally warriors mounted on horseback, knights became associated with the concept of chivalry as it was popularised in medieval European literature. Knights were expected to fight bravely and honourably and be loyal to their lord until death if necessary. Later chivalry came to encompass activities such as tournaments and hunting, and virtues including justice, charity and faith. The Crusades were instrumental in the development of the code of chivalry, and some crusading orders of knighthood, such as the Knights Templar, have become legend.

Boys would begin their knightly training at the age of seven, learning to hunt and studying academic studies before becoming assistants to older knights, training in combat and learning how to care for a knight's essentials: arms, armour, and horses. After fourteen years of training, and when considered master of all the skills of knighthood, a squire was eligible to be knighted.

In peacetime knights would take part in tournaments. Tournaments were a major spectator sport, but also an important way for knights to practice their skills - knights were often injured and sometimes killed in melees.

Knights figured large in medieval warfare and literature. In the 15th century knights became obsolete due to advances in warfare, but the title of 'knight' has survived as an honorary title granted for services to a monarch or country, and knights remain a strong concept in popular culture.

This short history will cover the rise and decline of the medieval knights, including the extensive training, specific arms and armour, tournaments and the important concept of chivalry.

Boys would begin their knightly training at the age of seven, learning to hunt and studying academic studies before becoming assistants to older knights, training in combat and learning how to care for a knight's essentials: arms, armour, and horses. After fourteen years of training, and when considered master of all the skills of knighthood, a squire was eligible to be knighted.

In peacetime knights would take part in tournaments. Tournaments were a major spectator sport, but also an important way for knights to practice their skills - knights were often injured and sometimes killed in melees.

Knights figured large in medieval warfare and literature. In the 15th century knights became obsolete due to advances in warfare, but the title of 'knight' has survived as an honorary title granted for services to a monarch or country, and knights remain a strong concept in popular culture.

This short history will cover the rise and decline of the medieval knights, including the extensive training, specific arms and armour, tournaments and the important concept of chivalry.

Just over a decade after the first successful powered flight, fearless pioneers were flying over the battlefields of France in flimsy biplanes. As more aircraft took to the skies, their pilots began to develop tactics to take down enemy aviators. Though the infantry in their muddy trenches might see aerial combat as glorious and chivalric, the reality for these 'Knights of the Sky' was very different and undeniably deadly: new Royal Flying Corps subalterns in 1917 had a life expectancy of 11 days.

In 1915 the term 'ace' was coined to denote a pilot adept at downing enemy aircraft, and top aces like the Red Baron, Rene Fonck and Billy Bishop became household names. The idea of the ace continued after the 1918 Armistice, but as the size of air forces increased, the prominence of the ace diminished. But still, the pilots who swirled and danced in Hurricanes and Spitfires over southern England in 1940 were, and remain, feted as 'the Few' who stood between Britain and invasion. Flying aircraft advanced beyond the wildest dreams of Great War pilots, the 'top' fighter aces of World War II would accrue hundreds of kills, though their life expectancy was still measured in weeks, not years.

World War II cemented the vital role of air power, and post-war innovation gave fighter pilots jet-powered fighters, enabling them to pursue duels over huge areas above modern battlefields. This entertaining introduction explores the history and cult of the fighter ace from the first pilots through late 20th century conflicts, which leads to discussion of whether the era of the fighter ace is at an end.

In 1915 the term 'ace' was coined to denote a pilot adept at downing enemy aircraft, and top aces like the Red Baron, Rene Fonck and Billy Bishop became household names. The idea of the ace continued after the 1918 Armistice, but as the size of air forces increased, the prominence of the ace diminished. But still, the pilots who swirled and danced in Hurricanes and Spitfires over southern England in 1940 were, and remain, feted as 'the Few' who stood between Britain and invasion. Flying aircraft advanced beyond the wildest dreams of Great War pilots, the 'top' fighter aces of World War II would accrue hundreds of kills, though their life expectancy was still measured in weeks, not years.

World War II cemented the vital role of air power, and post-war innovation gave fighter pilots jet-powered fighters, enabling them to pursue duels over huge areas above modern battlefields. This entertaining introduction explores the history and cult of the fighter ace from the first pilots through late 20th century conflicts, which leads to discussion of whether the era of the fighter ace is at an end.

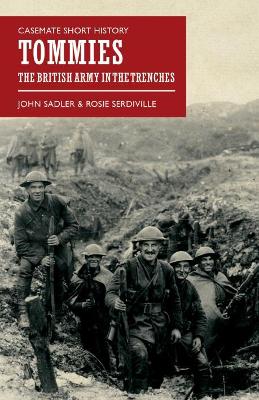

British soldiers have been known as Tommies for centuries, but the nickname is particularly associated with the British infantryman in the trenches of World War I.

In August 1914, a small professional force of British soldiers crossed the Channel to aid the French and Belgians as the German army advanced. As it became apparent that the war would not, in fact, be over by Christmas, a vast drive for volunteer soldiers began.

As enthusiasm for enlistment tailed off, eventually conscription was introduced in order to replenish the forces weakened by years of bloodshed. By 1918 the British Army was transformed, fielding 5.5 million men on the Western Front alone. These Tommies fought an entirely new type of war, living in vast trench systems, threatened by death from the air and gas attack as well as by bullet, bomb, or bayonet.

This introduction explores the experience of Tommies on the Western Front, explaining how their war evolved and changed from the mobile battles of August 1914 to the final days of the war, and discussing daily life as an infantryman on the front line using first-hand accounts, contemporary poems, and songs.

In August 1914, a small professional force of British soldiers crossed the Channel to aid the French and Belgians as the German army advanced. As it became apparent that the war would not, in fact, be over by Christmas, a vast drive for volunteer soldiers began.

As enthusiasm for enlistment tailed off, eventually conscription was introduced in order to replenish the forces weakened by years of bloodshed. By 1918 the British Army was transformed, fielding 5.5 million men on the Western Front alone. These Tommies fought an entirely new type of war, living in vast trench systems, threatened by death from the air and gas attack as well as by bullet, bomb, or bayonet.

This introduction explores the experience of Tommies on the Western Front, explaining how their war evolved and changed from the mobile battles of August 1914 to the final days of the war, and discussing daily life as an infantryman on the front line using first-hand accounts, contemporary poems, and songs.

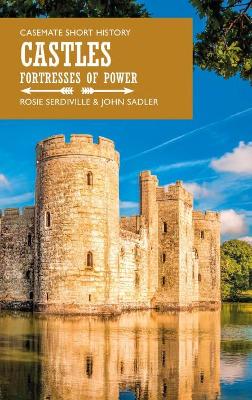

Fortified structures have been in existence for thousands of years. In ancient and medieval times castles were the ultimate symbol of power, dominating their surroundings, and marking the landscape with their imposing size and impregnable designs. After the Norman conquest of England, castles exploded in popularity amongst the nobility, with William the Conqueror building an impressive thirty-six castles between 1066-1087, including Windsor Castle is one example of such a castle which survives today, a monument of the remarkable architecture designed and developed in medieval England.

This concise and entertaining short history explores the life of the castle, one that often involved warfare and sieges. The castle was a first and foremost a fortress, the focus of numerous clashes which took place in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Castles became targets of sieges, such as that organised by Prince Louis of France against Dover castle in 1216, and were forced to adopt greater defensive measures.

Also explored is how they evolved from motte-and-bailey to stone keep castles, in the face of newly-developed siege machines and trebuchets. The trebuchet named Warwolf, which Edward I had assembled for his siege of Scotland’s Stirling Castle, reportedly took three months to construct and was almost four hundred feet tall on completion. With features such as ‘murder-holes’ for throwing boiling oil at the attackers, the defenders in the castle fought back in earnest. Alongside such violence, the castle functioned as a residence for the nobles and their servants, often totalling several hundred in number. It was the location for extravagant banquets held in the great hall by the lord and lady, and the place where the lord carried out his administrative duties such as overseeing laws and collecting taxes.

This concise and entertaining short history explores the life of the castle, one that often involved warfare and sieges. The castle was a first and foremost a fortress, the focus of numerous clashes which took place in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Castles became targets of sieges, such as that organised by Prince Louis of France against Dover castle in 1216, and were forced to adopt greater defensive measures.

Also explored is how they evolved from motte-and-bailey to stone keep castles, in the face of newly-developed siege machines and trebuchets. The trebuchet named Warwolf, which Edward I had assembled for his siege of Scotland’s Stirling Castle, reportedly took three months to construct and was almost four hundred feet tall on completion. With features such as ‘murder-holes’ for throwing boiling oil at the attackers, the defenders in the castle fought back in earnest. Alongside such violence, the castle functioned as a residence for the nobles and their servants, often totalling several hundred in number. It was the location for extravagant banquets held in the great hall by the lord and lady, and the place where the lord carried out his administrative duties such as overseeing laws and collecting taxes.

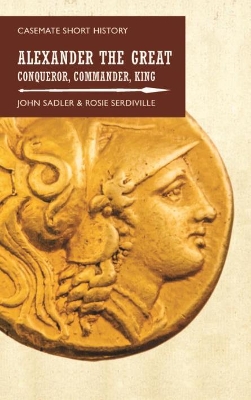

Alexander was perhaps the greatest conquering general in history. In just over a generation, his northern Greek state of Macedon rose to control the whole of the vast Persian Empire. It was the legacy of his father, Philip, that launched Alexander on a spectacular career of conquest that planted Hellenic culture across most of Asia. In a dozen years Alexander took the whole of Asia Minor and Egypt, destroyed the once mighty Persian Empire, and pushed his army eastwards as far as the Indus. No-one in history has equalled his achievement. Julius Caesar, contemplating his hero’s statue, is said to have wept because by contrast he had accomplished so little.

Much of Alexander’s success can be traced to the Macedonian phalanx, a close-ordered battle formation of sarissa-wielding infantry that proved itself a war-winning weapon. The army Alexander inherited from his father was the most powerful in Greece, highly disciplined, trained and loyal only to the king. United in a single purpose, they fought as one. Alexander recognized this and is quoted as saying, “Remember upon the conduct of each depends the fate of all.” Cavalry was also of crucial importance in the Macedonian army, as the driving force to attack the flanks of the enemy in battle. A talented commander, able to anticipate how his opponent would think, Alexander understood how to commit his forces to devastating effect, and was never defeated in battle. He also developed a corps of engineers that utilised catapults and siege towers against enemy fortifications. Alexander led from the front, fighting with his men, eating with them, refusing water when there was not enough, and his men would quite literally follow him to the ends of the (known) world, and none of his successors was able to hold together the empire he had forged. Although he died an early death his fame and glory persist to this day.

This concise history gives an overview of Alexander’s life from a military standpoint, from his early military exploits to the creation of his empire and the legacy left after his premature death.

Much of Alexander’s success can be traced to the Macedonian phalanx, a close-ordered battle formation of sarissa-wielding infantry that proved itself a war-winning weapon. The army Alexander inherited from his father was the most powerful in Greece, highly disciplined, trained and loyal only to the king. United in a single purpose, they fought as one. Alexander recognized this and is quoted as saying, “Remember upon the conduct of each depends the fate of all.” Cavalry was also of crucial importance in the Macedonian army, as the driving force to attack the flanks of the enemy in battle. A talented commander, able to anticipate how his opponent would think, Alexander understood how to commit his forces to devastating effect, and was never defeated in battle. He also developed a corps of engineers that utilised catapults and siege towers against enemy fortifications. Alexander led from the front, fighting with his men, eating with them, refusing water when there was not enough, and his men would quite literally follow him to the ends of the (known) world, and none of his successors was able to hold together the empire he had forged. Although he died an early death his fame and glory persist to this day.

This concise history gives an overview of Alexander’s life from a military standpoint, from his early military exploits to the creation of his empire and the legacy left after his premature death.