Oxford Archaeology Monograph

2 primary works

Book 4

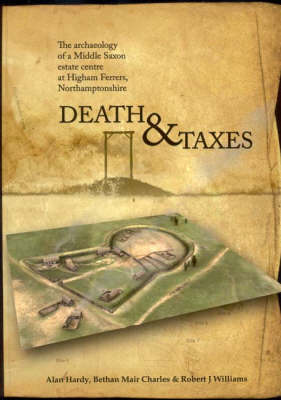

How did Middle Saxon kings govern their estates, and how did the mechanism of early forms of regional administration work? A spectacular site on the outskirts of Higham Ferrers in Northamptonshire has demonstrated that archaeology can add significantly to the debate. Between 1993 and 2003, Oxford Archaeology undertook a major programme of survey and excavation on the outskirts of the town, uncovering extensive remains dating from the Middle Bronze Age to the late medieval period. This volume deals with the Anglo-Saxon and medieval remains, and concentrates on a large 8th-century complex of enclosures and buildings, along with other structures including a large malting oven. It is argued that this represents the infrastructure of a purpose-built tribute centre for a royal estate. The character of the material evidence indicates that wide variety of produce came into complex and was then redistributed rather than consumed on site. The centre administered judicial as well as economic affairs. Evidence of the human remains from an execution site was found - some of it possibly linked to the sudden demise of the tribute centre at the beginning of the 9th century. In addition, the evidence of a well-preserved Reduced Ware pottery manufactory is an indicator of the later role of the area as an industrial estate of the medieval borough of Higham Ferrers.

Book 16

A Road Through the Past

by Alan Hardy, Kelly Powell, Tim Allen, and Michael Donnelly

Published 15 October 2012

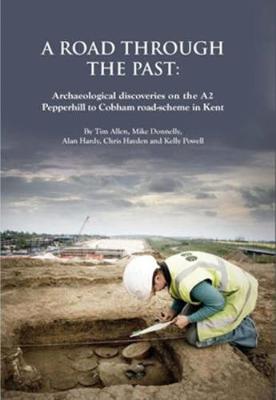

Excavations along the new road line have revealed nearly 6000 years of human activity, from a massive marker post erected by early Neolithic farmers at the head of a dry valley to a bizarre burial of several different animals dating to the sixteenth century AD. Prehistoric discoveries include two enclosures of the middle Bronze Age, both associated with some of the earliest cobbled roads in Kent, a collection of Iron Age storage pits rich in diverse deliberate offerings, and the emergence of a nucleated hamlet in the middle Iron Age.

Most exciting were rich cremation burials of the late Iron Age and early Roman periods, probably successive generations of a local family, whose rise to prominence coincides with the growth of the cult centre at Springhead nearby. The metal vessels include types new to Britain, the pottery stamps suggest the movement of continental potters to Kent, and one grave has the clearest evidence of furniture yet found from early Roman Britain. Medieval settlements of the late 11th-14th centuries mirror the renewed importance of Watling Street after the Norman conquest, and its eventual return to obscurity due to competition from the ferry from London to Gravesend.

Most exciting were rich cremation burials of the late Iron Age and early Roman periods, probably successive generations of a local family, whose rise to prominence coincides with the growth of the cult centre at Springhead nearby. The metal vessels include types new to Britain, the pottery stamps suggest the movement of continental potters to Kent, and one grave has the clearest evidence of furniture yet found from early Roman Britain. Medieval settlements of the late 11th-14th centuries mirror the renewed importance of Watling Street after the Norman conquest, and its eventual return to obscurity due to competition from the ferry from London to Gravesend.