American Made Music

4 total works

To Do This, You Must Know How traces black vocal music instruction and inspiration from the halls of Fisk University to the mining camps of Birmingham and Bessemer, Alabama, and on to Chicago and New Orleans. In the 1870s, the Original Fisk University Jubilee Singers successfully combined Negro spirituals with formal choral music disciplines, and established a permanent bond between spiritual singing and music education. Early in the twentieth century there were countless initiatives in support of black vocal music training conducted on both national and local levels. The surge in black religious quartet singing that occurred in the 1920s owed much to this vocal music education movement.

In Bessemer, Alabama, the effect of school music instruction was magnified by the emergence of community-based quartet trainers who translated the spirit and substance of the music education movement for the inhabitants of working-class neighborhoods. These trainers adapted standard musical precepts, traditional folk practices, and popular music conventions to create something new and vitalBessemer's musical values directly influenced the early development of gospel quartet singing in Chicago and New Orleans through the authority of emigrant trainers whose efforts bear witness to the effectiveness of ""trickle down"" black music education. A cappella gospel quartets remained prominent well into the 1950s, but by the end of the century the close harmony aesthetic had fallen out of practice, and the community-based trainers who were its champions had virtually disappeared, foreshadowing the end of this remarkable musical tradition.

In Bessemer, Alabama, the effect of school music instruction was magnified by the emergence of community-based quartet trainers who translated the spirit and substance of the music education movement for the inhabitants of working-class neighborhoods. These trainers adapted standard musical precepts, traditional folk practices, and popular music conventions to create something new and vitalBessemer's musical values directly influenced the early development of gospel quartet singing in Chicago and New Orleans through the authority of emigrant trainers whose efforts bear witness to the effectiveness of ""trickle down"" black music education. A cappella gospel quartets remained prominent well into the 1950s, but by the end of the century the close harmony aesthetic had fallen out of practice, and the community-based trainers who were its champions had virtually disappeared, foreshadowing the end of this remarkable musical tradition.

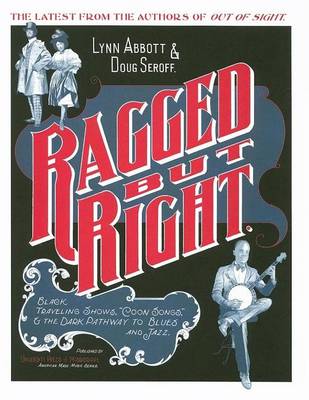

The commercial explosion of ragtime in the early twentieth century created previously unimagined opportunities for black performers. However, every prospect was mitigated by systemic racism. The biggest hits of the ragtime era weren't Scott Joplin's stately piano rags. ""Coon songs,"" with their ugly name, defined ragtime for the masses, and played a transitional role in the commercial ascendancy of blues and jazz.In Ragged but Right, now in paperback, Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff investigate black musical comedy productions, sideshow bands, and itinerant tented minstrel shows. Ragtime history is crowned by the ""big shows,"" the stunning musical comedy successes of Williams and Walker, Bob Cole, and Ernest Hogan. Under the big tent of Tolliver's Smart Set, Ma Rainey, Clara Smith, and others were converted from ""coon shouters"" to ""blues singers.""Throughout the ragtime era and into the era of blues and jazz, circuses and Wild West shows exploited the popular demand for black music and culture, yet segregated and subordinated black performers to the sideshow tent. Not to be confused with their nineteenth-century white predecessors, black, tented minstrel shows such as the Rabbit's Foot and Silas Green from New Orleans provided blues and jazz-heavy vernacular entertainment that black southern audiences identified with and took pride in.

From 1889 to 1895, the fire that would ignite almost every American popular music style was sparking. These were some of the worst years in American race relations, yet they witnessed the emergence of ragtime and the birth of an African American popular entertainment industry. Out of Sight is the first book dedicated to this signal period of black musical development. It is a landmark study, based on thousands of music-related references mined by the authors from a variety of contemporaneous sources, especially African American community newspapers. The citations are organized and explained in a way that clears a path through the dense landscape of this neglected period in black music history. Accompanying the text are 150 halftones, also excavated from period sources, offering a broad pictorial canvas of African American music during the years before ragtime's commercial ascendancy. Out of Sight examines musical personalities, issues, and events in context. It confronts the inescapable marketplace concessions musicians made to the period's prevailing racist sentiment. With detail never available in a book before, it describes the worldwide travels of jubilee singing companies, the plight of the great black prima donnas, and the evolutions of ""authentic"" African American minstrels. With its access to newspapers and photos, Out of Sight puts a face on musical activity in the insular black communities of the day. Drawing on hard-to-access archival sources and song collections, the book is of crucial importance for understanding the roots of jazz, blues, and gospel. It is essential for comprehending the evolution and dissemination of African American popular music from 1900 to the present. Out of Sight paints a rich picture of musical variety, personalities, issues, and changes during the period that shaped American popular music and culture for the next hundred years. Lynn Abbott is an independent scholar living in New Orleans. His work has been published in American Music, 78 Quarterly, American Music Research Center Journal, and The Jazz Archivist. Doug Seroff is an independent scholar living in Greenbrier, Tenn. His work has appeared in American Music, Black Music Research Newsletter, Blues Unlimited, and Record Exchanger, among others. A leading expert on black gospel quartet singing for twenty-five years, he has written chapters published in anthologies and many scholarly essays for a wide variety of journals.

Blues Book of the Year -Living Blues

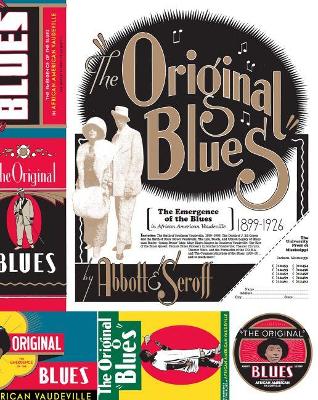

With this volume, Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff complete their groundbreaking trilogy on the development of African American popular music. Fortified by decades of research, the authors bring to life the performers, entrepreneurs, critics, venues, and institutions that were most crucial to the emergence of the blues in black southern vaudeville theaters; the shadowy prehistory and early development of the blues is illuminated, detailed, and given substance.

At the end of the nineteenth century, vaudeville began to replace minstrelsy as America's favorite form of stage entertainment. Segregation necessitated the creation of discrete African American vaudeville theaters. When these venues first gained popularity ragtime coon songs were the standard fare. Insular black southern theaters provided a safe haven, where coon songs underwent rehabilitation and blues songs suitable for the professional stage were formulated. The process was energized by dynamic interaction between the performers and their racially-exclusive audience.

The first blues star of black vaudeville was Butler "String Beans" May, a blackface comedian from Montgomery, Alabama. Before his bizarre, senseless death in 1917, String Beans was recognized as the "blues master piano player of the world." His musical legacy, elusive and previously unacknowledged, is preserved in the repertoire of country blues singer-guitarists and pianists of the race recording era.

While male blues singers remained tethered to the role of blackface comedian, female "coon shouters" acquired a more dignified aura in the emergent persona of the "blues queen." Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and most of their contemporaries came through this portal; while others, such as forgotten blues heroine Ora Criswell and her protege Trixie Smith, ingeniously reconfigured the blackface mask for their own subversive purposes.

In 1921 black vaudeville activity was effectively nationalized by the Theater Owners Booking Association (T.O.B.A.). In collaboration with the emergent race record industry, T.O.B.A. theaters featured touring companies headed by blues queens with records to sell. By this time the blues had moved beyond the confines of entertainment for an exclusively black audience. Small-time black vaudeville became something it had never been before-a gateway to big-time white vaudeville circuits, burlesque wheels, and fancy metropolitan cabarets. While the 1920s was the most glamorous and remunerative period of vaudeville blues, the prior decade was arguably even more creative, having witnessed the emergence, popularization, and early development of the original blues on the African American vaudeville stage.

With this volume, Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff complete their groundbreaking trilogy on the development of African American popular music. Fortified by decades of research, the authors bring to life the performers, entrepreneurs, critics, venues, and institutions that were most crucial to the emergence of the blues in black southern vaudeville theaters; the shadowy prehistory and early development of the blues is illuminated, detailed, and given substance.

At the end of the nineteenth century, vaudeville began to replace minstrelsy as America's favorite form of stage entertainment. Segregation necessitated the creation of discrete African American vaudeville theaters. When these venues first gained popularity ragtime coon songs were the standard fare. Insular black southern theaters provided a safe haven, where coon songs underwent rehabilitation and blues songs suitable for the professional stage were formulated. The process was energized by dynamic interaction between the performers and their racially-exclusive audience.

The first blues star of black vaudeville was Butler "String Beans" May, a blackface comedian from Montgomery, Alabama. Before his bizarre, senseless death in 1917, String Beans was recognized as the "blues master piano player of the world." His musical legacy, elusive and previously unacknowledged, is preserved in the repertoire of country blues singer-guitarists and pianists of the race recording era.

While male blues singers remained tethered to the role of blackface comedian, female "coon shouters" acquired a more dignified aura in the emergent persona of the "blues queen." Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and most of their contemporaries came through this portal; while others, such as forgotten blues heroine Ora Criswell and her protege Trixie Smith, ingeniously reconfigured the blackface mask for their own subversive purposes.

In 1921 black vaudeville activity was effectively nationalized by the Theater Owners Booking Association (T.O.B.A.). In collaboration with the emergent race record industry, T.O.B.A. theaters featured touring companies headed by blues queens with records to sell. By this time the blues had moved beyond the confines of entertainment for an exclusively black audience. Small-time black vaudeville became something it had never been before-a gateway to big-time white vaudeville circuits, burlesque wheels, and fancy metropolitan cabarets. While the 1920s was the most glamorous and remunerative period of vaudeville blues, the prior decade was arguably even more creative, having witnessed the emergence, popularization, and early development of the original blues on the African American vaudeville stage.