Cambridge Library Collection - Monographs of the Palaeontographical Society

7 total works

A Monograph on the Fossil Reptilia of the Cretaceous Formations

by Richard Owen

Published 18 September 2015

The Cretaceous sediments of southern England (dating from 145 million to 83 million years ago) have yielded a plethora of fossil reptile specimens, ranging from flying reptiles to gigantic marine predators. The most famous of these, the dinosaurs, are known mainly from the rocks of the Wealden Group, which were deposited by rivers and streams. However, other Cretaceous formations laid down by the sea, including the Lower and Upper Greensand and the Chalk Group, have provided key information on reptile evolution during the 'middle' part of the Cretaceous period. Sir Richard Owen (1804–92) assessed all of the fossil reptile material at his disposal and summarised many of his findings in the monograph on Cretaceous reptilia (published with four supplements in 1851–64). This included new information on the dinosaur Iguanodon and on plesiosaurs, but was concerned mainly with fossil turtles, flying reptiles (pterosaurs) and marine lizards (mosasaurs and their relatives).

Monograph On the Fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck Formations

by Richard Owen

Published 30 April 2015

Sir Richard Owen (1804-92) coined the term 'Dinosauria' in 1842 for the remains of three animals named from the Middle Jurassic and Early Cretaceous rocks of southern England: Megalosaurus, Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus. In his monograph on the Wealden and Purbeck Reptilia (published in five parts with nine supplements in 1853-79) he confirms the distinctiveness of this newly recognised group, building on earlier work by Gideon Mantell and others. Owen also reviewed the other reptiles then known from these Early Cretaceous faunas, including turtles, crocodiles and lizards. This work initiated major interest in the earliest Cretaceous Purbeck Limestone Group fauna, which remains one of the most diverse small reptile faunas known from the Mesozoic, as well as consolidating the international importance of the Wealden Group in dinosaur studies. The monograph remains a benchmark for many of the species described, particularly the crocodiles and turtles.

A Monograph of the Fossil Reptilia of the Liassic Formations

by Richard Owen

Published 27 April 2015

Discoveries of fossil reptiles in the sea cliffs of south-western England helped to consolidate ideas of 'deep time' and extinction by revealing ancient worlds whose unfamiliar and bizarre inhabitants had no living counterparts. Many of these fossils were from the Lower and Upper Lias Groups, suites of rocks laid down in the shallow seas that covered much of southern England during the Early Jurassic period (around 201-174 million years ago). Sir Richard Owen (1804–92) was one of several anatomists who provided extensive descriptions of these animals. His monograph on the Liassic Reptilia (published in three parts in 1861–81) includes the first, and so far only, detailed description of the early armoured dinosaur Scelidosaurus (the first dinosaur known from an almost complete skeleton), an important account of Dimorphodon (the first flying reptile named from the United Kingdom), and critical information on two marine reptile groups, the plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs.

A Monograph of the Fossil Malacostracous Crustacea of Great Britain...

by Thomas Bell

Published 2 September 2011

Unlike some other reproductions of classic texts (1) We have not used OCR(Optical Character Recognition), as this leads to bad quality books with introduced typos. (2) In books where there are images such as portraits, maps, sketches etc We have endeavoured to keep the quality of these images, so they represent accurately the original artefact. Although occasionally there may be certain imperfections with these old texts, we feel they deserve to be made available for future generations to enjoy.

Monograph on the Fossil Reptilia of the London Clay

by Richard Owen and Thomas Bell

Published 3 November 2011

Covering a wide area of the London and Hampshire basins, the London Clay has been famous for over two hundred years as one of the richest Eocene strata in the country. In this work, first published between 1849 and 1858, Fellows of the Royal Society Richard Owen (1804–92) and Thomas Bell (1792–1880) describe their findings from among the reptilian fossils found there. The book is divided into four parts, covering chelonian, crocodilian, lacertilian and ophidian fossils, and includes an extensive section of detailed illustrations. Using his characteristic 'bone to bone' method and an emphasis on taxonomy, Owen draws some significant conclusions; he shows that some of Cuvier's classifications were wrongly extended to marine turtles, and adds to the evidence for an Eocene period much warmer than the present. The work is a fascinating example of pre-Darwinian palaeontology by two scientists later much involved in the evolutionary controversy.

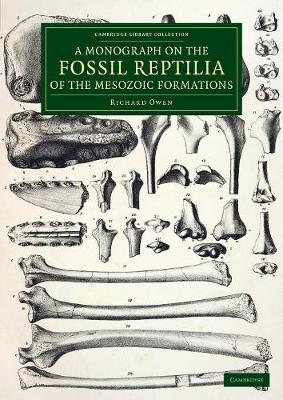

A Monograph on the Fossil Reptilia of the Mesozoic Formations

by Richard Owen

Published 30 April 2015

Sir Richard Owen (1804–92) produced a series of monographs on the fossil reptiles found in the Mesozoic and Tertiary rocks of the United Kingdom, describing a wide variety of fossil lizards, turtles, crocodiles, flying reptiles (pterosaurs), marine reptiles and dinosaurs, many of which were new to science and whose names remain in use today. Most of the monographs concentrated on faunas from specific geological formations, but the one Owen began writing as the last in this series, on the Mesozoic Formations (originally published in 1874–7 and gathered together in 1889) described material ranging from the Middle Jurassic through to the Early Cretaceous. It includes the first scientific description of a stegosaurian dinosaur (Omosaurus), which preceded the naming of Stegosaurus from the United States by two years, extensive notes on Jurassic and Cretaceous pterosaurs, and some of the earliest descriptions of the unusual air-filled vertebrae of sauropod dinosaurs.

Monograph on the Reptilia of the Kimmeridge Clay and Portland Stone

by Richard Owen

Published 27 April 2015

The discovery of marine reptiles in the Jurassic rocks of central and southern England helped spark a revolution in the earth sciences, opening new vistas on deep time and revealing a variety of animals whose bizarre appearances kick-started long-standing public fascination with extinct life. Sir Richard Owen (1804–92) was at the forefront of this work and described many new species of ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs and mosasaurs. In this monograph on the Reptilia from the Kimmeridge Clay and Portland Stone (originally published in 1861–9 and gathered together in 1889) Owen concentrated on the 'pliosaurs' from those units - large-bodied marine reptiles with huge heads, short necks and flippers - and showed that dinosaurs were not the only extinct reptile group to produce formidable predators. These formations have yielded abundant 'pliosaur' material, and Owen's monograph, reissued here with his 1870 study of cetacea from the Red Crag Formation, has remained the foundation for all subsequent work on these animals.