Jo

Written on Jun 9, 2018

Originally posted on Once Upon a Bookcase.

Trigger Warning: This book features mental illness stigma, self-harm, several suicide attempts, and suicide. This review discusses the self-harm and attempted suicide in this book.

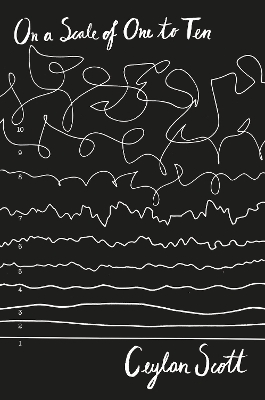

I wanted to review On a Scale of One to Ten by Ceylan Scott for Mental Illness in YA Month as it was an #OwnVoices novel for borderline personality disorder (BPD). While the story was written well, and has a lot to say on mental illness, I finished feeling pretty disappointed.

Tamar has just been admitted to a psychiatric ward for teenagers after a suicide attempt. Tamar has been self-harming for a number of years now, ever since the death of Iris. Because she killed her. Because she's evil and disgusting, and doesn't deserve to live, when Iris died. The doctors ask Tamar question after question, but unlike with every other patient, they can't seem to figure out what she has. On a Scale of One to Ten is the story of life on a psychiatric ward, coming to terms with the past, and trying to live when you don't know what's wrong with you.

On a Scale of One to Ten is a really well written, quick read. It's deeply affecting, and doesn't at all shy away from the dark side of mental illness. It's honest and raw and visceral, and, I guess, important. The story is told in alternating chapters of Then and Now, showing the events that lead up to Tamar entering the psychiatric ward, and life in the psychiatric ward. Tamar is really struggling with Iris' death. It's been two years now, but her mental health has just worsened. And what's worse, no-one seems to know what's wrong with her. All she knows is that she is evil, she is disgusting, she is worthless. She doesn't deserve to live, and can't stop thinking about ending her life.

'I don't tell him that the desire for death has been raging through my veins like a stampede of angry bulls, and that every fibre of my disgusting being should be charred and powdered in a dusty crematorium.' (p128-129)

'"Can you tell me what's been bothering you these past few days? You've been seeming quite unsettled to some of the staff, would you agree with that?"

"Yeah, I suppose."

"Why?"

Why? I can ponder that question in my sedated brain for days and I still won't have any answers. It's hard to make space for other thoughts when you only want to kill yourself. In fact, it's hard to make space for anything. It's hard to make space for remembering to eat or piss or smile when it's expected of you.' (p129-130)

Tamar also really struggles with the fact that the doctors can't seem to figure out what's wrong wi th her. It's only at the very end of the book, when she's being discharged and she gets to take home her case-management notes, that we read 'Her symptoms are concurrent with a personality disorder borderline).' (p215) But Tamar isn't told what the doctor or the nurses think while on the ward. She seems to be a puzzle to them, unable to work out what it is she has. And there's frustration and fear in not knowing what's wrong, and not getting the help she needs.

'They gave me antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers. Because that's all they could do. Other patients could talk for hours in their sweaty-palmed state about their anxiety disorder. The eating-disorder patients, trapped in their unhealthy relationships with food, some of them emaciated, others not a pound off normal. The patients with such crippling depression that even getting out of bed in the morning was an achievement worthy of more than a pat on the back.

The monster that had swallowed me was different. The experts soon exhausted their options: manic depression, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder . . . But the monster didn't need a label or a name. The monster was me.' (p170)

'"How can we help you, Tamar?"

"You're the doctor."

He nods. "You're right, I am. I can give a diagnosis, I can prescribe medication, but I can't--"

"What's wrong with me, then?" I say. "You tell everyone else what's wrong with them - Jasper's an anorexic, Elle's bipolar. What am I? Or am I just making all this up to waste your time?"' (p127)

It's really difficult to watch this struggle, and it's heartbreaking that it takes so long for her to get a diagnosis. I know for me that knowing for definite that I had anxiety, and knowing what that meant and how it affected my body and why, made all the difference to me. Understanding my mental illness took away some of the fear. I knew what was "wrong" with me, and I knew why, and although it was scary having a panic attack, understanding why my body was behaving the way it was, was helpful. I can't even image what it's like to know something isn't right, but not knowing what, and knowing doctors can't seem to figure it out either.

On a Scale of One to Ten also covers is the stigma surrounding mental illness...

'My illness didn't command sympathy and grapes and bunches of flowers. No sympathy for psychos. People didn't want to have anything to do with that girl, the one who sliced her own skin for fun. But I wasn't trouble; I was in trouble.' (p32)

...mostly in the form of Tamar's former not-quite-friend, Mia. Mia bullied Tamar when she was younger, until Mia became friends with Tamar's best friend, Toby, and a not-quite friendship was formed because of him. Mia visits Tamar at the psychiatric ward, on the day of Iris' birthday, and blows her top.

'"I actually can't believe you, Tamar! You just swan around like everything is so much harder for you, when it's not! It's fucking not, OK? Life is shit for everyone, it's shit for me too, but that doesn't mean we all have to start moping around and slitting our wrists for everyone to see. You're a fucking idiot. You just used Iris as an excuse to get attention, everyone can see it. You weren't even that close to her. She was just some girl in our class."' (p105-106)

Although I don't have the same mental illness as Tamar, simply having a mental illness, I reacted quite strongly to this. I felt sick and angry and upset, and I just wanted to cry. Mia's remarks aren't aimed at me, and yet this is the attitude so many have towards mental illness in general. I really don't understand how people don't get it. They don't need to have a mental illness to get it, it's called empathy. I don't understand how people could think those of us with mental illnesses just want attention, that we're faking it, being drama queens and over dramatic. I really don't get it. If I could choose not to have anxiety, I would.

Unsurprisingly, Tamar doesn't react well to Mia's outburst. She was already not doing ok because it was Iris' birthday - the guilt and the hatred and the certainty that she is why Iris is dead, yet she is alive - and Mia just pushes her over the edge. Tamar attempts suicide int he bath with three razor blades she smuggled in. I'm not going to quote it in my review, but the scene is really quite graphic, and it was so, so difficult to read - even though I knew she would be ok, because there was still half the book to go. It was described so well, and with such a choice of words - "spewing", "spurts" - that you can't help but see it happen. I think some may have a negative reaction to simply reading this in my review, to know there's such a graphic suicide attempt, but I think it's important. Suicide is not pretty or romantic, it can be something out of a horror movie. And also, Tamar regrets it as soon as it's done, so we also see her panic and scream for help, and her desire to live. She's lucky, they manage to save her, but sometimes there's no going back from a suicide attempt, and I think it's important to see how quickly - in an instant, when Tamar thinks she might actually die - she regrets it. How she desperately wants to cling to life.

When it comes to BPD, though, there's not really much I can say about it, because I don't feel like I know what it is. There's a lot of talk when it comes to diverse books about mirrors and windows; they should be mirrors for those from marginalised groups so they can see themselves in the characters, and windows for those who aren't part of those marginalised groups, to see and understand characters unlike themselves. From the reviews on Goodreads, it's clear to see that On a Scale of One to Ten is very much a mirror, it's had so many reviews from people with BPD raving about it and how it was spot on. But - and perhaps it's just me missing things - I didn't feel it was much of a window; I don't know any more about BPD than I did before picking up the book. I couldn't tell you how it manifests or what it's symptoms are. We get some medical jargon at the end of the book from Tamar's case-management notes, which gives some kind of idea, but I'm still really none-the-wiser. However, maybe it's just that On a Scale of One to Ten isn't for me. Perhaps it's for those who do have BPD, and if so, it's obviously doing it's job. And as I'm pretty sure I haven't come across any other books featuring BPD (if you know of others, please do let me know!), this book is hugely important for those teens with BPD, as this is a book they can read to see themselves in.

However, for all it's good, there are elements of On a Scale of One to Ten I found quite disappointing. The characters, for the most part, are two dimensional. The only thing we know about Tamar as a person outside of her mental illness is she used to enjoy being part of the cross country team at school, and really enjoyed running. She makes friends at the ward with Alice, Jasper and Elle, but we know nothing about them as people, who they are, outside of their mental illnesses. Alice and Jasper are anorexic, Elle has bipolar. We know Elle has been in foster care since she witnessed her mother overdoes as a baby. But none of that tells us about who she is as a person. Jasper is funny, and Elle is a bit out there, but that's pretty much down to her bipolar. Otherwise, we know nothing about any of the characters. Nothing. And that's so very frustrating.

Overall, On a Scale of One to Ten is an important and deeply affecting novel that will do a lot of good for BPD readers. It's heartbreaking, but hopeful, and we really need more stories like this, with characters getting the help they need (even if it's a struggle to work out what that help is).

Thank you to Chicken House for the review copy.