viking2917

Written on Jan 9, 2017

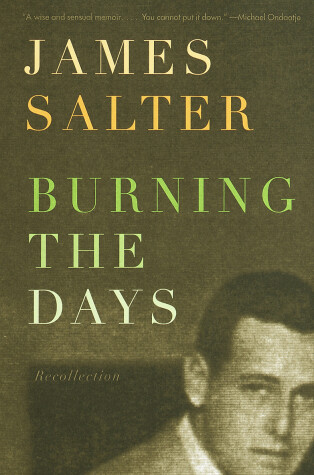

Some time ago I was wandering through a used bookstore in Manchester by the Sea and stumbled across Burning the Days, the memoir of the writer James Salter. The well known book reviewer Michael Dirda of the Washington Post famously wrote “he can, when he wants, break your heart with a sentence.”. I opened the book to a random page, and found:

I cannot think of it without sadness. I think of the day-long, intimate hours in her apartment with the same record playing over and over, phrases from it like some sort of oath I will know til the day I die.

OK it’s two sentences. Salter is an amazing writer, and behind that lies a fascinating, complex, insightful man. Burning the Days tells the story of his life, from the early days of learning about sex through to his early 70’s. The transience of all things is lurking on every page, but the book rings out with its joys as well.

In youth it feels one’s concerns are everyone’s. Later on it is the clear that they are not. Finally they again become the same. We are all poor in the end. The lines have been spoken. The stage is empty and bare.

Before that, however is the performance. The curtain rises.

His description of becoming aware of sex is priceless. After a friend tells him stories, this:

Months later one noon, looking through the magazines in a cigar store, I came across a pamphlet with blue covers. Some had placed it there, concealed behind a magazine; it was not part of the stock. The provocative title I have forgotten, but as I began to read I underwent a conversion. …fairly trembling with discovery, like someone who has found a secret letter, I hid the precious thing. I was going to try certain things, and all that I had read, in time, I found to be true.

Years afterwards, at a luncheon, I sat next to a green-eyed young woman, a poet, who declared loftily that you learned nothing from books, it was life you learned from, passion, experience. The host, a fine old man in seventies, heard her and disagreed. His hair was white. His voice that the faint shrillness of age. “No, everything I’ve ever learned,”, he said, “has come from books. I’d be in the darkness without them.”

I didn’t know if he was speaking of Balzac or Strindberg…. but in no particular order I tried to think of books that had instructed me, and among them, not insignificant, was the anonymous twenty page booklet in blue covers that described the real game of the grownup world.

At The Hawaii Project, we often say Books Change Lives. And they do.

His time at West Point was equally formative.

The most urgent thing was to somehow fit in, to become unnoticed, the same. My father had managed to do it, although, seeing what it was like, I did not understand how.

During his studies at West Point, a number of books figure prominently. But one book changed his life.

There was one with the title Der Kompaniechef, the company commander. This youthful but experienced figure was nothing less than a living example to each of his men. Alone, half obscured by those he commanded, similar to them but without their faults, self-disciplined, modest, cheerful, he was at the same time both master and servant, each of admirable character. His real authority was not based on shoulder straps or rank but on a model life which granted the right to demand anything from others.

An officer, wrote Dumas, is like a father with greater responsibilities than an ordinary father. The food his men ate, he ate, and only when the last of them slept, exhausted, did he go to sleep himself. His privilege lay in being given these obligations and a harder duty than any of the rest.

The company commander was someone whom difficulties could not dishearten, privation could not crush. It was not his strength that was unbreakable but something deeper, his spirit. He must not only have his men obey, they must do it when they are absolutely worn out and quarreling among themselves, when they are at the end of their rope and another senseless order comes down from above.

He could be severe but only when it was needed and then briefly. It had to be just, it had to wash things clean like a sudden, fierce storm...

I knew this hypothetical figure. I had seen him as a schoolboy, latent among the sixth formers, and at times had caught a glimpse of him at West Point. Stroke by stroke, the description of him was like a portrait emerging. I was almost afraid to recognize the face. In it was no self-importance; that had been thrown away, we are beyond that, stripped of it. When I read that among the desired traits of the leader was a sense of humor that marked a balanced and indomitable outlook, when I realized that every quality was one in which I instinctively had faith, I felt an overwhelming happiness, like seeing a card you cannot believe you are lucky enough to have drawn, at this moment, in this game.

I did not dare to believe it but I imagined, I thought, I somehow dreamed, the face was my own.

I began to change, not what I truly was, but what I seemed to be. Dissatisfied, eager to become better, I shed as if they were old clothes the laziness and rebellion of the first year and began anew.

To the anonymous poet mentioned above: yes, Books Change Lives. If they are good enough, and if we let them. On my reading, I was struck by how much this fictional company commander resembles the Leonidas of Gates of Fire, by Steven Pressfield, of which I’ve written elsewhere.

The first phase of Salter’s life is military, eventually becoming a pilot, and Burning the Days chronicles that life in ways that are by turns comical, heartwarming, and searing. This phase of his life leads to his first novel The Hunters, and flying the Korean War, and his true tales from that time open a window into the military experience few books can match.

The success of The Hunters eventually drives him to leave the Army and write full time. He discovers Paris. This leads him to write A Sport and A Pastime, an erotic chronicle of Paris, with an unreliable narrator. He goes into movies, writing screenplays for a number of films, most of them unsuccessful (I’ve recently become aware of how many writers of that era put food on the table by writing screenplays — Steven Pressfield is another). His stories of the movies, the stars, and set locations are thought provoking as well as interesting.

And always, there are the books. The books he’s writing, the books he’s reading — I’ve picked up 3 or 4 books other than his own, that meant something to him.

What a fascinating man and life. A fighter pilot, a man’s man, a serial womanizer it seems, and yet deeply introspective and caring. An aesthete, intimately aware of the transient nature of all things. Burning the Days is simultaneously elegiac and joyful, and will give you insightful perspective on life.